Czech Republic Smetana, The Bartered Bride (Prodaná nevěsta): Soloists, National Theatre Opera Ballet, Members of the Continuo Theatre, Dancers and Members of the Prague Philharmonic Children’s Choir, National Theatre Chorus and Orchestra / David Švec (conductor). National Theatre, Prague, 1.9.2021. (RP)

Czech Republic Smetana, The Bartered Bride (Prodaná nevěsta): Soloists, National Theatre Opera Ballet, Members of the Continuo Theatre, Dancers and Members of the Prague Philharmonic Children’s Choir, National Theatre Chorus and Orchestra / David Švec (conductor). National Theatre, Prague, 1.9.2021. (RP)

Production:

Director – Magdalena Švecová

Sets – Petr Matásek

Costumes – Zuzana Přidalová

Choreographer – Ladislava Košíková

Chorusmaster – Pavel Vaněk

Dramaturgy – Ondřej Hučín

Cast:

Mařenka – Dana Burešová

Jeník – Jaroslav Březina

Kecal – Jiří Sulženko

Vašek – Josef Moravec

Krušina – Ivan Kusnjer

Ludmila – Maria Kobielska

Mícha – František Zahradníček

Háta – Yvona Škvárová

Ringmaster – Jan Ježek

Esmeralda – Zuzana Kopřivová

Indian – Lukáš Bařák

The Bartered Bride is family fare in the Czech Republic, and there were plenty of children in the National Theatre who were transfixed by its sights and sounds at this first performance of the season. The much-beloved, quintessentially Czech opera, replete with the rural sensibilities of the nineteenth century, comes with a message in the opening chorus, however, that is perfectly in accord with this moment in time.

‘Let us rejoice, let’s be merry

while the Lord grants us good health,

who knows whether this time next year

all of us shall still be here.’

Since the opera premiered here in 1866, Prague has seen far darker days than the current pandemic, but simple pleasures such as sitting in a theater are appreciated more than they were just a short time ago. The delight of the experience was evident on stage, in the pit and in the audience.

Despite its present-day popularity, the opera was not an immediate success, and it only gained a foothold in the repertoire after Bedřich Smetana reworked it extensively. It was, nonetheless, performed over one hundred times during his lifetime, making it the first Czech opera to achieve that distinction.

After Smetana’s death, The Bartered Bride found a champion in Gustav Mahler, whose admiration for the opera prompted him to incorporate a quote from the overture into the final movement of his First Symphony. Mahler introduced the opera to audiences in Hamburg, Vienna and New York, and added it to the Metropolitan Opera’s repertoire when he was its music director in 1909. The Bartered Bride is now firmly entrenched in the standard repertoire, although most international audiences heard the opera in German until relatively recently.

It is a retelling of a timeless story with a twist. A young couple – Mařenka and Jeník – are in love, but she is promised to another. Upon learning of the terms of his rival’s nuptial contract from the marriage broker, Kecal, Jeník agrees to forsake Mařenka for a payment of 300 florins, but he insists that the contract specify she can only marry a son of Tobiáš Mícha. Unbeknownst to Mařenka, her parents, the marriage broker and the villagers, the mysterious Jeník is the elder son of Tobiáš Mícha, and was driven from home by his stepmother, Háta.

Vašek, the child of his father’s second marriage, is a likable halfwit with no real interest in marriage. He is, however, delighted by the bear suit which he dons to save a traveling circus from ruin, and is susceptible to the charms of Esmerelda, a Spanish dancer who coaxes him into it. Mařenka is shattered to learn that Jeník has sold her to another man, but relents when she learns of Jeník’s true identity and motivations. The only person unhappy with the outcome is Háta, who reluctantly concedes that the young man running around in a bear suit is probably not yet marriage material.

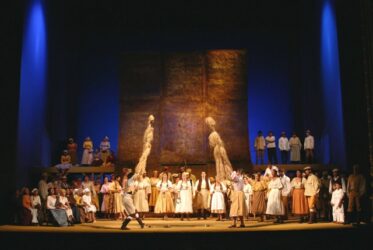

This is a revival of Magdalena Švecová’s 2008 production, which was the twentieth mounted by the company and the first directed by a woman. That the production maintains its freshness and appeal is due in equal parts to Švecová’s realistic characterizations and Petr Matásek’s simple but attractive set, much of which resembles nothing so much as parts of a ski slope. The sets, like Zuzana Přidalová’s costumes, are inspired by nature, and the color of wheat predominates in both.

There are broad comic touches, such as Kecal’s cart pushed by lackeys, which serves as his means of transport as well as his desk. His appearance is always announced by a honk of the horn. One of the most enchanting sights are the red poppies that dot the fields framing much of the action. They are the same color as the red umbrella that crowns Kecal’s cart, and they brighten many of the costumes. Folk dances are performed with gusto, and the circus really comes to town, complete with arial acrobatic performances.

This menagerie of characters came alive with subtle characterizations and solid singing. Dana Burešová instilled Mařenka with a certain steeliness which was also evident in her gleaming soprano. She melted hearts, however, when singing of her love for Jeník and, later, expressing her heartbreak at being tossed aside for his apparent greed. As the object of her affections, tenor Dana Burešová was no youthful swain but a man of the world. His comic touch was light but always sure, while his singing was full of ardor.

The two lovers are central to the tale, but it was the machinations of Jiří Sulženko’s Kecal that made it come alive. One couldn’t quite say that he stole the show, but in many ways he was the show. Veteran baritone Ivan Kusnjer as Krušina was a masterclass in acting. With the smallest of gestures, he could convey the conflicted emotions of a father torn between daughter and duty.

In the midst of all the action, but seeming oblivious to it all, was Josef Moravec’s wonderful Vašek. Moravec’s bright tenor and his general cluelessness were a winning combination. As his mother, Yvona Škvárová didn’t have much to sing, but she was a commanding presence. With a headpiece adorned with ribbons as stiff as airplane propellors and her voluminous billowy dress, one good blast of air would have lifted her and her haughtiness skywards.

As with the singers and dancers, Smetana’s score is in the souls of conductor David Švec and the players that he led in the pit. The well-known overtures brimmed with energy, and the dances were played with remarkable vigor. Who could begrudge the young girl sitting next to me tapping her toe?

Rick Perdian