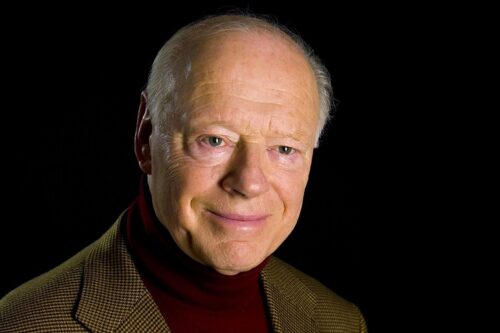

Seen and Heard International is deeply saddened to hear of the passing of Bernard Haitink and reproduces the statements from the London Symphony Orchestra and the Royal Opera House

The London Symphony Orchestra was deeply saddened to learn of the death of Bernard Haitink, who passed away at the age of 92 on 21 October.

Bernard Haitink’s first appearances with the LSO took place in 1998 at the Barbican, a series of three concerts featuring music by Haydn, Bruckner and Mahler, which marked the start of a relationship that deepened through performances, recordings and tours over the subsequent two decades. He conducted the Orchestra in 2004 as part of the LSO’s centenary year, in a concert that also celebrated his own 75th birthday, and in 2006 conducted a complete cycle of the Beethoven Symphonies, the recordings of which are still considered to be among the finest in the repertoire.

Bernard Haitink’s tours with the Orchestra took in performances across Europe, the United States, Japan and Korea, and at an LSO concert in 2003 he was presented with the ABO (Association of British Orchestras) Award by Sir Simon Rattle. In 2019 he joined the Orchestra in London and Paris for concerts celebrating his 90th birthday, described by The Times as ‘music making of the highest order’.

Sir Simon Rattle, Music Director of the London Symphony Orchestra said: ‘It is so hard to imagine that Bernard has left us: he was a constant presence and inspiration to all of his fellow musicians, and the world seems a smaller and less generous place this morning.

Although I had been watching and listening to him throughout my teens, we first met in Glyndebourne In 1975 where I was a pianist for the legendary Hockney/John Cox production of The Rake’s Progress. Bernard taught me an indelible lesson there: the piano score is famously tricky to play, but if he was on the rostrum I found I could play it all without faking or missing out handfuls of notes. It must have been something to do with the space he imparted, the how and why remains a mystery, but it was abundantly clear that I could not play it in the same way if he was not conducting. Although I had witnessed great conductors previously, this was my first direct experience of the immense difference that one person’s presence could make. It is a microcosm of all I saw him do throughout his career. Without fuss, and utterly without drawing attention to himself, he created a place where everyone could give their best and normal problems of ensemble or balance simply vanished. It became almost a commonplace to think “if we can’t play well under Bernard, it’s time to take up another profession.”

I found him warm and encouraging from the first moment on, and although I tried not to bother him, if I needed advice or was in a crisis, he was always there, generous with time, wisdom and empathy. I owe him more than I can put into words: he was a famously difficult man to thank or congratulate, the lack of fuss once more. But I think, however unwillingly, he must have sensed the love and gratitude around him.

My heart goes out to Patricia who has surrounded him with more love and care than anyone could wish, and who has been as selfless and generous as her husband. He was one of the rare giants of our time, and even rarer and more precious, a giant full of humility.

My dear Bernard, we keep you deep in our hearts.’

David Alberman, Principal Second Violin and Chair of the London Symphony Orchestra, said: ‘Bernard Haitink will be hugely missed by all of us in the LSO – and by our colleagues in other orchestras – who had the privilege of working with him. His vast humanity, and mysterious but unmistakable ability to change the sound of an orchestra with his mere presence, are unforgettable. The few words he needed in rehearsal belied the depth and breadth of his knowledge of both the score at hand, but of all related literature – whether music or word. This he distilled down to small but irresistible gestures – a minute inclination of the head, for instance, to listen to a leading voice would immediately make us want to do the same, and problems of balance simply melted away. The result was apparently effortless but powerfully moving music, and a strong feeling that he enjoyed making us into the best musicians we could be. We enjoyed it too!

Our thoughts are with his wife Patricia and all of his family at this sad time; but we also give thanks for his long life, particularly the last 20 years, during which we shared so many memorable performances – the Beethoven Symphony cycle being a particular highlight.’

A statement from the Royal Opera House where he was The Royal Opera’s Music Director (1987-2002)

Bernard Haitink was born in Amsterdam, studied violin and conducting at the Amsterdam Conservatory and joined the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic, first as a violinist and later as Principal Conductor, a position he held from 1957 until 1961. He went on to become the youngest ever Principal Conductor of the Concertgebouw Orchestra (1961–88), Principal Conductor of the London Philharmonic Orchestra (1967–79) and Music Director of Glyndebourne Festival Opera (1977–88). He made his Royal Opera debut in 1977, when he conducted Don Giovanni and Lohengrin.

Conducting highlights during his tenure as Music Director of The Royal Opera included new productions of Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro and Don Giovanni, Strauss’s Die Frau ohne Schatten, Borodin’s Prince Igor, Tchaikovsky’s The Queen of Spades, Smetana’s The Bartered Bride, and three Janáček operas including the first performances of Kát’a Kabanová at Covent Garden. Among other performances, Haitink also conducted revivals of Verdi’s Don Carlos and Britten’s Peter Grimes to great acclaim.

But it was perhaps as a Wagner interpreter he was best known with The Royal Opera. During his tenure he conducted two Ring cycles (directed by Götz Friedrich and Richard Jones), along with new productions of Parsifal, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg and Tristan und Isolde. The Spectator described his 1988 Parsifal as ‘faultlessly paced… the ritual elements had true splendour’, while the Independent hailed ‘the glories of Bernard Haitink’s work with the orchestra’ in his 1995 interpretation of Götterdämmerung, and the Guardian considered his 1993 Meistersinger ‘the high point of his tenure’.

Haitink’s final appearance as Music Director of The Royal Opera came in July 2002, when he conducted a gala of extracts from some of his favourite works – Le nozze di Figaro, Don Carlo and Die Meistersinger. He returned to the Company in 2007 to conduct Parsifal, in performances The Guardian hailed as ‘at once noble and sensual’ and The Telegraph as ‘reaching into the Wagnerian sublime’.

Haitink went on to be Chief Conductor of the Staatskapelle Dresden (2002–4) and Principal Conductor with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (2006–10). He was appointed Conductor Laureate of the European Union Youth Orchestra in 2015. For several years he gave masterclasses for young conductors in Lucerne. His many awards included Honorary Companion of Honour (UK, 2002) and Commander of the Order of the Netherlands Lion (2017).

Principal flautist of the Orchestra of the Royal Opera House Margaret Campbell said: ‘As our Music Director Bernard was universally loved and admired. He allowed us to play. He coaxed a beautiful sound out of the strings. He trusted his players and gave soloists in the orchestra considerable freedom to express themselves, helping us along with an atmosphere of mutual respect. He had a wonderful sense of musical architecture and never lost the thread of the piece however long it was.

He was charismatic, respectful and truly inspirational. To share with him the deep emotion and indeed frivolities of the operas and ballets we played together was a tremendous privilege for all of us in the Orchestra of the Royal Opera House. We count ourselves truly blessed.’

Music Director of The Royal Opera Antonio Pappano said: ‘Bernard was a towering musician whose warmth and total honesty in his music-making made his performances always ring true. He guided the Royal Opera House through a most challenging period safeguarding the standard of the orchestra and chorus and I, personally, shall be forever in his debt. He was a beloved figure and will be truly missed.’

Chief Executive of the Royal Opera House Alex Beard said: ‘This is a deeply sad day for the Royal Opera House and for music. Bernard was a true gentleman and his exceptional musicianship, quiet authority and profound care and respect for his fellow artists inspired and moved beyond words. All our thoughts are with Patricia and all those who loved him.’

Chair of the Royal Opera House’s Board of Trustees Simon Robey said: ‘We are thankful for the gifts that Bernard gave us. He held the audience awed and spellbound for some of the truly greatest evenings in the Royal Opera House’s history. He was a hero to us all.’