Austria Mahler, Von der Liebe Tod (From Love Death): Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of Vienna State Opera / Lorenzo Viotti (conductor). Livstreamed (directed by Dominik Kepczynski) from Vienna State Opera, 7.10.2022. (JPr)

Austria Mahler, Von der Liebe Tod (From Love Death): Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of Vienna State Opera / Lorenzo Viotti (conductor). Livstreamed (directed by Dominik Kepczynski) from Vienna State Opera, 7.10.2022. (JPr)

Mahler – Das klagende Lied and Kindertotenlieder

Production:

Director – Calixto Bieito

Set design – Rebecca Ringst

Costume design – Ingo Krügler

Lighting – Michael Bauer

Stage design assistant – Annett Hunger

Singers:

Florian Boesch (baritone)

Vera-Lotte Boecker (soprano)

Monika Bohinec (mezzo-soprano)

Daniel Jenz (tenor)

Johannes Pietsch (boy soprano)

Jonathan Mertl (boy alto)

Gustav Mahler became director of the Vienna Hofoper (now Staatsoper) in 1897 and having reinvigorated the opera house it ended ten years later in mutual recriminations, rather like Philippe Jordan’s current planned departure from his post as music director there at the end of 2025. Mahler’s first love – I have always insisted – was opera and it was just the lack of time that prevented him composing one (or more) … and of course he did not live long enough. Had his cantata Das klagende Lied actually won the 1881 Beethoven prize for which it was entered who knows what direction Mahler’s career would have gone in? It is operatic in character and has huge instrumental and choral demands; it also employs four adult soloists with declamatory interventions but not often much to sing, as well as a boy soprano and boy alto. Mahler’s use of a high voiced boy to sing the words of the haunted flute was inspired.

The original version of Mahler’s Das klagende Lied (as performed here) is in three movements and in this epic fairy tale two brothers set out (Waldmärchen / Forest Legend) in search of a red flower that will allow one of them to marry a queen. The gentle blond brother finds it, the evil brown one murders his brother in his sleep, steals the flower and the promised bride. In part II (Der Spielmann) the minstrel of the title picks up one of the slain brother’s bones, makes a flute from it, which sings the story of how he was killed in part I – ’Song of Lamentation’ of the title – and there is so much additional lamentation, sorrow and woe! In part III (Hochzeitsstück / Wedding Piece) the minstrel rushes to the queen’s castle and at the end as the remaining bridegroom-brother plays the fateful flute, the queen slumps to the floor and down come the castle walls to end with even more sorrow and more woe.

In the absence of no other Mahler stage work (although there is always his completion of Weber’s opera Die drei Pintos which is hardly ever seen and heard) this was uninterruptedly paired with the composer’s later Kindertotenlieder (Songs on the Death of Children) to mark the 125th Vienna anniversary. These were later considered by the composer’s wife, Alma, as tempting fate, following the death of Maria, one of their own daughters. Friedrich Rückert’s original poetry was written to reflect his own feelings of loss after the death of one of his sons, Ernst. The Kindertotenlieder (written between 1901 and 1904) were first performed in Vienna in January 1905, five years after Das klagende Lied was premiered there.

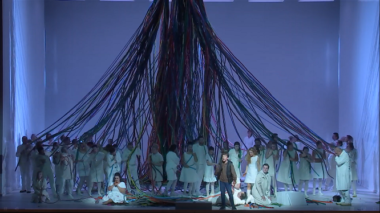

Spanish theatre director – and opera enfant terrible – Calixto Bieito returned to Vienna to stage these in the dystopian future of Rebecca Ringst’s stark white set (and matching costumes) which concentrates on the digital highway with its preponderance of colourful cables which dominate most of what we see. For me they look partly like the ribbons on a maypole or the plastic Scoubidou threads of blessed childhood memory. The effects of climate change are probably suggested by the chorus bringing on potted plants at the beginning which are initially suspended like a forest. The tenor (Daniel Jenz) brings a cooler box to the front of the stage which contains some soil to plant the red-flowered plant important to the story we watch unfold. Dirt will be smeared about quite a lot, and the first blood we see is when the princess seems pricked by the one of the flowers before there is a lot more when the prone boy (Jonathan Mertl as The Minstrel) loses his arm from which is hacked out the bone for the flute and near the end when the princess cuts out her tongue possibly because of all the tragedy her challenge has wrought.

The slain brother (Johannes Pietsch) has pulled a sheet up over himself and this leads us into Kindertotenlieder where he is embraced by baritone Florian Boesch during ‘Nun seh’ ich wohl, warum so dunkle Flammen’. The five songs are sung fairly straight and are all the better for it. The only distraction is some people in partywear who fringe the stage with fluorescent paint pots and long-handled brushes to daub the walls with random symbols. It will be hard not be become emotionally connected with the songs but that is more due to Mahler than Bieito and because of the exceptional performances they get from Boesch (the father) and mezzo-soprano Monika Bohinec (the mother). Only the hardests of hearts cannot be failed to be moved by the final song ‘In diesem Wetter’ as (a very emotional) Boesch regrets letting the children go out in some appalling weather when he was worried they would fall ill. Holding hands with Bohinec tears well up as Boesch sings how ‘With no storm to frighten them, cradled in god’s hand, they’re resting as if at home’ before they slowly walk off as the lights fade. Memorably fabulous singing.

For me the ending absolved Bieito of all that went before, about which I remain rather ambivalent. It was wonderful to hear Mahler performed by members of ‘his’ Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra in ‘his’ opera house. Of course, I have to remind readers I was listening through loudspeakers but under Lorenzo Viotti (who was making his Staatsoper debut) there was all the luminous virtuosity you would expect from the orchestra. Along with his well-cast soloists and the impressively detailed singing from the chorus, Das klagende Lied was given a dramatic coherence that became so much more than the sum of its splendid individual parts. Boesch’s warm expressive baritone stood out, supported by Bohinec’s rich, contralto-like timbre and the piping tones of Jonathan Mertl (boy alto) and Johannes Pietsch (boy soprano) who showed precocious composure. Tenor Daniel Jenz and soprano Vera-Lotte Boecker had much less to sing but revealed – due to the nature of Bieito’s staging – that they too are fine singing-actors.

Jim Pritchard