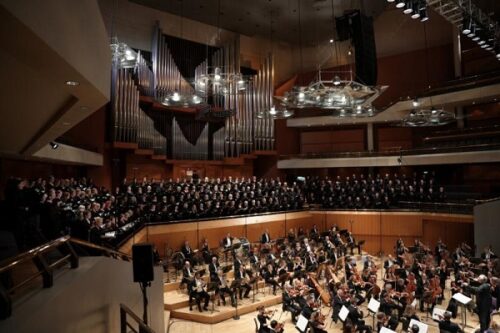

United Kingdom Elgar: Sophie Bevan and Gemma Summerfield (sopranos), Alice Coote and Dame Sarah Connolly (mezzo-sopranos), Ed Lyon and Andrew Staples (tenors), Roderick Williams, David Stout and Ashley Riches (baritones), Clive Bayley (bass), Apostles Chorus from Royal Northern College of Music, Hallé Choir and Associates, London Philharmonic Choir, Ad Solem University Choir, Hallé Orchestra / Sir Mark Elder (conductor). Bridgewater Hall, Manchester, 10-11.6.2023. (PCG)

United Kingdom Elgar: Sophie Bevan and Gemma Summerfield (sopranos), Alice Coote and Dame Sarah Connolly (mezzo-sopranos), Ed Lyon and Andrew Staples (tenors), Roderick Williams, David Stout and Ashley Riches (baritones), Clive Bayley (bass), Apostles Chorus from Royal Northern College of Music, Hallé Choir and Associates, London Philharmonic Choir, Ad Solem University Choir, Hallé Orchestra / Sir Mark Elder (conductor). Bridgewater Hall, Manchester, 10-11.6.2023. (PCG)

Elgar – The Apostles, Op.49; The Kingdom, Op.51

I travelled from South Wales to Manchester for the weekend for this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to experience Elgar’s two Biblical oratorios performed how he specified: as a single work over two concerts on consecutive days. So far as I can ascertain, this was the first such performance since the composer’s death. Even with crowded trains and Manchester street closures as the local football team celebrated some historic sporting victory, it was well worth the expense and trouble.

In the first place, the event demonstrated conclusively that the two oratorios do make up one unified work. Elgar comprehensively amalgamates his thematic material, and that was repeatedly shown beyond argument. Consider how he takes the simplicity of Jesus’s opening statement of the Beatitudes in By the wayside, the second movement of The Apostles, and transforms it into the soaring climax of the aria The sun goeth down towards the end of The Kingdom. Such command of motivic material exceeds his Wagnerian prototype so far that to hear the second oratorio in isolation would be to miss out on a whole dimension of the musical structure.

Sir Mark Elder was clearly fully aware of these implications. Think of the graduated manner in which – during the first part of The Apostles – the long rising chromatic sequence associated with Christ’s solitary prayer in the mountains emerges through the music which accompanies the rising of the day to the glorious apotheosis of the foundation of the Church. That might have seemed to exhaust the possibilities of the theme in the glorious explosion of sound which Elder elicited from his vast body of performers. But then, when at the climax of the Ascension the theme erupts once again over the battering triplet rhythm, he showed a keen awareness of the moment: he managed to pile Pelion on Ossa to achieve a climax that seemed to lift the roof from the hall.

Elder also showed a keen sense of the dramatic implications endemic in Elgar’s Biblical epic. In comparison with earlier performances on record by Boult and by Hickox, and with his own recording (which derived from a Manchester concert a decade ago), Elder showed much concern for realism and the thrill of the narrative. What also helped was the stage disposition of the soloists: Christ to the left, the two Marys by his side; on the other side, Saint John and Saint Peter grouped with Judas and the nine other disciples as a semi-chorus. The arrangement left two small acting areas to either side of the podium. They were tastefully exploited by Mary Magdalene and Judas during their substantial solo scenes, and encouraged a manner of delivery of the texts which went well beyond mere pious reproductions of the holy scriptures. The semi-chorus of apostles, which Elder had introduced ten years ago after his study of Elgar’s own performance notes, was a real plus in this performance. I would never wish to hear those parts once again consigned to the body of the chorus as in the Elgar and Hickox recordings.

Oher theatrical touches included the shepherds’ distant piping in the mountains and the shofar (ram’s horn) on the temple roof removed to the back of the chorus on the extreme right of the stereo picture. One only wished for the choral dialogue between Christ and his Father during the Ascension to have been similarly distinguished geographically, with the ‘chorus mysticus’ placed further back and higher in the hall. But the tone of the two bodies of singers was distinct enough.

After the intensity of The Apostles with its dramatic succession of events, The Kingdom, more contemplative – little physically happens, apart from the Whitsun sequence and the healing of the lame man – may seem like a letdown. Never mind that it has the longer and better-known musical numbers such as Peter’s address to the people of Jerusalem or The sun goeth down. The latter established early a semi-independent existence in the days of 78s, as did the prelude conducted by Elgar, the only passage from the oratorios he ever recorded. Even in that prelude the listener was forcibly struck by the quiet, almost whispered, reminiscence of the music from The Apostles where Peter denied Christ. The passage is meaningless musically and dramatically unless the audience recognises the reference. Elder did not allow the music at any point to stagnate, and the dynamic contrasts between an almost inaudible whisper and the stentorian thunder of the massed forces were just as strong here as before. One wondered again and again how Elgar unerringly manages to build his massive climaxes from existing material. Even the final setting of the Lord’s Prayer, which Vaughan Williams had regarded as rather an anticlimax, came across as part of an extended slow-dying fall. (The music is reminiscent of the Second Symphony, to come a few years later.)

It was perhaps necessary, but still unfortunate, to cast two independent teams of soloists for each of the two evenings. One would not have thought that the admittedly strenuous roles would have been more taxing for the individual singers than, say, a Wagnerian cycle. There were also two last-minute substitutions. That cannot have made life easier for the performers when the music for the principal quartet is so often closely integrated, let alone when a further semi-chorus is added to the mix in The Apostles. As it was, the late substitute Andrew Staples in The Kingdom closely matched the tones of Ed Lyon who sang Saint John the night before. Dame Sarah Connolly and Alice Coote lent plangency and drama to the role of Mary Magdalene. The other late substitute, Sophie Bevan, took over as the Virgin Mary in The Apostles. She was superbly matched with Gemma Summerfield’s creamy tones in The Kingdom.

The first evening, David Stout had been a very forthright and down-to-earth Saint Peter; after his betrayal he seemed to have taken the decision to withdraw into himself. When Ashley Riches took over the role in The Kingdom, he was more considerate and generally quieter of tone; one could have welcomed more trenchant delivery in his address to the people. Judas, a gift of a part for a dramatic deep bass, was beautifully sung by Clive Bayley. His acting and superbly inflected diction gave real depth to Elgar’s depiction of his character.

It has been a tradition for the role of Jesus to go to a gentler and lighter baritone voice, often with minimal vibrato. Here, Roderick Williams gave us a more emotional aspect with richly rounded tones and a degree of humanity which Elgar himself – who after all wanted his apostles to seem like ordinary men – would doubtless have welcomed.

When I reviewed Elder’s CD release of The Apostles ten years ago, I took issue with a couple of his interpretative decisions. Both were addressed here. The shepherds’ pipes in the distance of the night-shrouded mountains now had the freedom of phrasing that Elgar seems to have have sought with his ironically very precise notation. And the oddly hesitant interruption of Judas’s repentance by the priests’ triumphant cry of Selah! was now hair-raising in its glorification of violence. The singing of the massed choirs was stunning, with a force and engagement that defy description in words. At the end of The Apostles, with the rise to a high sustained soprano and tenor B-flat over the full orchestral forces plus organ, the sound had a positively Mahlerian effect. Their quiet singing, equally stunning, included the dangerously exposed high writing from the semi-chorus during the Whitsun sequence in The Kingdom.

This was not simply a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to hear the two oratorios as Elgar wished them to be played; it was a once-in-a-lifetime performance of anything. It was all the more horrendous that the hall was less than half full the first evening; more people came along for The Kingdom but even then not to full capacity. I met people who had come from all over the country specifically for these performances; where were the Manchester audiences?

The programme thankfully informed us that the BBC, clearly aware that those were historic concerts, had scheduled The Apostles for broadcast on 28 June with continuing availability for the next month. Audiences worldwide should make every effort to hear it, simply the greatest performance of the work we may ever be likely to encounter. It was not perfect, one does not expect perfection in a work of such dimensions. One hopes that the BBC engineers might be able to smother the motor-horn effect which interrupted Christ’s last words before the Ascension, or edit out the over-eager and very stentorian tenor chorister who pushed ahead of his brethren on the temple roof as they hailed the coming of the dawn. With these two minor adjustments, and the addition of The Kingdom to the broadcast, we would have the best representation of these two works in the catalogues of recorded music. The sound of the Hallé horns as they rang out in confident unison during the closing bars of Part One of The Kingdom vindicated Elgar’s incredibly stressful and dangerous. I have never yet heard anything like it in any performance.

I have two niggles with the hall. The Hallé have been considerate enough to prepare separate programme booklets with the complete texts of the oratorios; the obvious intention was for audiences to keep abreast of the events described in the music. It is, therefore, not sensible to turn the lights in the auditorium too low for the texts to be readable. And, given the increased age and fragility of concert audiences nowadays (alas), surely there should be more provision for seating in the vast and impressive foyer of the building itself? Apart from the designated seating area for bar customers, I saw a single bench along one wall, with a maximum capacity of eight people.

No matter. Thanks to Sir Mark and the Hallé for an unmissable event with which everybody concerned can be thoroughly satisfied. The two amply illustrated programme books, with notes by the late Michael Kennedy and with Sir Mark Elder’s personal essay, were models of what such things should be. ‘Let’s do him proud!’ said Sir Mark of Elgar. Indeed.

Paul Corfield Godfrey

I concur with everything that was said about ‘The Kingdom’; unfortunately, a family gathering prevented me from attending ‘The Apostles’, but I can`t wait for the recorded relay.

I also agree with the lack of foyer seating being a major oversight, at The Bridgewater Hall.

I drove up from London for the day with my wife to hear this performance of The Apostles. It was a stunningly moving experience, and all praise must go to Mark Elder and his assembled forces for their achievement. The reviewer does full justice to the scale and impact of the event in all but one respect. I, too, was disappointed that the hall was not sold out, but to say it was “less than half full” is something of an overstatement, and those lucky enough to be there were united in their ecstatic response.

I should certainly have mentioned the enthusiastic response of the audience to the performance – a standing ovation lasting several minutes. But the number attending certainly seemed small (in my row of the stalls some six seats out of thirty were actually occupied, and some parts of the hall seemed almost devoid of occupants); there were more for The Kingdom on the second evening. Nevertheless I am delighted to note that the BBC relay (which managed to minimise the two slips I mentioned, which hardly disturbed concentration) was engineered in the highest quality. Anybody who cares about this score owes it to themselves to hear the broadcast while it still remains available. It really was something very special indeed.

Over the weekend of Friday evening June 1st, Saturday evening June 2nd and Sunday afternoon June 3rd 2007, in celebration of Elgar’s ‘150th Birthday’, Sakari Oramo with CBSO forces performed all three oratorios – Dream of Gerontius, The Apostles & The Kingdom – on successive days in the Symphony Hall, Birmingham. Doesn’t that count?

Alan Cook

It is always dangerous to allege that something is (or is not) a first event; and I was sure that someone would let me know if since Elgar’s death there had been a previous performance of the oratorios on consecutive days. I am delighted to learn from Mr Cook that there had indeed been a precedent – and not too long ago, either. My apologies to the CBSO performers for my failure to note their pioneering efforts, which I am sure were excellent – and, as I say, emphasise the point that The Apostles and The Kingdom really benefit from being performed as a unit.