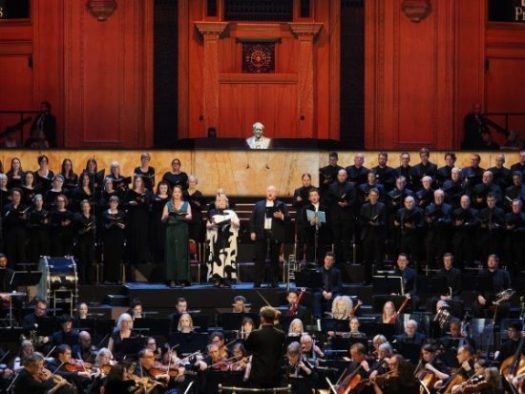

United Kingdom Prom 12 – Helen Grime, Beethoven: Eleanor Dennis (soprano), Karen Cargill (mezzo-soprano), Nicky Spence (tenor), Michael Mofidian (bass-baritone), BBC Symphony Chorus, BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra / Ryan Wigglesworth (conductor). Royal Albert Hall, London, 23.7.2023. (CC)

United Kingdom Prom 12 – Helen Grime, Beethoven: Eleanor Dennis (soprano), Karen Cargill (mezzo-soprano), Nicky Spence (tenor), Michael Mofidian (bass-baritone), BBC Symphony Chorus, BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra / Ryan Wigglesworth (conductor). Royal Albert Hall, London, 23.7.2023. (CC)

Helen Grime – Meditations on Joy (2019, BBC co-commission, UK premiere)

Beethoven – Symphony No.9 in D minor, Op.125, ‘Choral’ (1822-24)

This Prom was a real triumph for the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra under their Chief Conductor, Ryan Wigglesworth. Fabulous programming, real care in performance, with Beethoven heard afresh and, for UK audiences, Helen Grime heard completely fresh.

I thoroughly enjoyed Grime’s Whistler Miniatures (2011) and her Aviary Sketches (after Joseph Cornell) of 2014 at the Sheffield Chamber Music Festival in May last year (review here), which was preceded by a roundtable on music and art; while her Clarinet Concerto was the clear highlight of a Bath Chamber Orchestra concert at London’s Kings Place in 2021 (review here).

Perhaps Meditations on Joy is the finest of them all. The composer has stated that at the time she started composing this work (2019), she was not feeling a lot of joy in the process of composition, and it was something of a dark time. It was a book of poetry concentrating on joy that caused her to consider what joy is, and how it can appear unexpectedly. The first movement is dark, melancholy, the second has a ‘bubbling excitement’ that ‘cannot be contained’ and which ‘bursts forth’ while the finale concerns bliss and being at one with the environment. Finally, the music ‘disperses,’ leaving a lullaby.

The whole piece is only around a quarter of an hour long, but the impact of the music is huge. From the retrained, overlapping lines of the opening, a creeping slow-moving bass melody and a tolling bell, the feeling is of the monumental, despite the short duration. Colour (timbre) s brilliantly used, and all credit to the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra for their sheer advocacy and accuracy of execution. Few composers can surely count themselves so lucky: the belief in the piece from the players shone through from first note to last. The second movement glistens and glitters, highly rhythmic and yet initially held on a quiet level, brass accents stab through the texture, here perfectly executed. This was orchestral virtuosity at the complete service of a revelatory piece of music. The first violins’ long, disjunct melody is simply beautiful – a real underlining that ‘modern’ music really can touch the soul. In the programme, Grime is quoted as saying that her language is ‘detailed and intricate,’ and how clearly this was borne out on this occasion. The finale is Grime’s version of Impressionism: hazy, indistinct, languid. Like the master Impressionists, the scoring is perfect. It is clear Grime knows exactly what she wishes to achieve – here, not only an atmosphere, but also a restatement of that baseline lyricism that has underpinned the entire work, from the slower moving melody of the first movement to its ending now. And again, the overlappings of the first movement reappear, now faster, definitely more quixotic, an impression enhanced by silvery percussion.

Ryan Wigglesworth’s knowledge of the score was never in doubt as he coaxed the very best from his players – and what an ensemble the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra is now! This was world-class playing. This was the UK premiere of a major orchestral work. Commissioned by the BBC, the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin and the Los Angeles Philharmonic and premiered in LA in February this year. Meditations on Joy will receive its German premiere in October.

And so, onto one of the most famous hymns (odes) to joy there is: Beethoven’s vast Ninth Symphony. It felt a little less vast here, thanks to swift speeds across the board and an emphasis on clarity that added a measure of lightness to Beethoven’s score. Lithe yet dramatic, Wigglesworth’s first movement was tensile and direct, hard-sticked timpani making real punctuating points. Listen to the woodwind dialogues against the semiquaver figures tossed around the strings and marvel anew at Beethoven’s invention. Definition was everywhere (including from the first two horns); Beethoven’s hairpins were superbly and carefully rendered, yet each carried energy and then retreated. Most of all, the climax of the movement made a real impact.

The agility of the BBC SSO players by this time was hardly in doubt, but if proof be needed, point right towards the scampering Scherzo. The timpani again powered through the textures; horns and oboe were nimble in the fast Trio. And yet what really stood out here was Wigglesworth’s foregrounding of the contribution from the trombones. So often one only realises their weight in the doublings of the great finale, but here they created a new, richer soundworld for Beethoven.

The slow movement moved as one might by this stage expect. The woodwind worked brilliantly as a ‘choir’ (an aggregate, really), creating myriad colours. The first violins were preternaturally together (at this speed, those semiquavers were quite rapid) and a special mention for the orchestra’s fourth horn (yes, the solo was played by the fourth). Interpretatively, it was the pulsing violas, insistent, disturbing, that made a real mark. No plateau of rest, this.

Inter-movement applause blighted the entire symphony, but nowhere so poignantly than between the third and fourth movements. Arguments about whether Beethoven intended a segue there or not apart, it was very clear that Wigglesworth did, but the second the final chord of the slow movement stopped, so started the clapping!

The players did retain concentration, though, to deliver a wide-ranging finale, with the famous theme emerging quietly, very quietly, after significant struggle. It was clear there was a long way to go yet, and as the timpani thundered prior to the bass-baritone’s entrance, it was clear the struggle was not over.

For once, all four members of the solo vocal quartet were excellent. Michael Mofidian carried real gravitas in that first vocal statement (actually moving over to join the choral basses for the exchange of calls of ’Freude’). The pairs of voices worked well, too – when Nicky Spence’s tenor and Mofidian’s bass-baritone sit against Eleanor Dennis’s soprano and Karen Cargill’s mezzo, the effect was wonderful. Wigglesworth’s attention to dynamics, and the maintenance of a proper piano and pianissimo – leant this Beethoven Ninth a remarkably variegated hue.

All credit to the sopranos of the BBC Symphony Chorus for negotiating Beethoven’s perilous demands in the lead-in to and the arrival at ’vor Gott!’; and how one relished the luxury casting of Spence at the ensuing ’Froh, wie seine Sonnen fliegen’. The double fugue was a hive of activity and ever-increasing tension. After the choral outburst at ‘Freude, schöner Götterfunken’, Wigglesworth again brought the trombones to prominence – now, not just doubling the choral line but an entity unto themselves in the light of what we heard earlier. And if the sopranos excelled, earlier, they were matched by the gentlemen at ’über’m Sternenzelt!’

Fascinating that Wigglesworth manages to get the cantus firmus-feel later on as the longer duration choral statements came through – as if highlighting Beethoven’s debt to the polyphonists who preceded hm. When the solo quartet emerged from the prevailing choral sound at ‘Alle Menschen werden Brüder’, the effect was supremely beautiful – the finely honed quartet a major contributing factor, of course.

This was a freshly conceived, brilliant reading of the Ninth performed to the very highest standard by the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, with the BBC Symphony Chorus in fine fettle. A Proms Ninth to be remembered, for sure.

Colin Clarke

This was the best, freshest performance of Beethoven’s Ninth I have ever heard in my 82 years. Congratulations to everyone involved including the sound engineers who miked it perfectly but mostly to Ryan Wigglesworth for his interpretation.