Germany Fritz Kreisler, Sissy: Bremen Theatre Soloists and Children’s chorus, Students of Davenport ballet school, Bremen Philharmonic / Stefan Klingele (conductor). Bremen Theatre, 23.12.2025. (DM-D)

Germany Fritz Kreisler, Sissy: Bremen Theatre Soloists and Children’s chorus, Students of Davenport ballet school, Bremen Philharmonic / Stefan Klingele (conductor). Bremen Theatre, 23.12.2025. (DM-D)

In 1854, Emperor Franz Joseph I (1830-1916), in power since 1848, married his cousin Elisabeth, (called Sissi, 1837-1898). The Emperor’s mother, Archduchess Sophie, had been instrumental in bringing about his marriage – Sissi was the younger daughter of her sister, Duchess Ludovica, who in turn was married to Duke Maximilian in Bavaria (1808-1888). In 1931, Ernst Décsey and Gustav Holm (pen name for Robert Weil) wrote a comedy, Sissi’s Brautfahrt, about the alleged romantic meeting of Franz Joseph and Elisabeth (called Sissi in the play). In 1932, brothers Ernst and Hubert Marischka used the play as the basis of their text for an operetta, with music by violin virtuoso Fritz Kreisler (1875-1962). Without acknowledging the comedy, Ernst Marischka created three Sissi films in 1955, 1956 and 1957, of 102-, 101- and 109-minutes length, respectively. which have become cult films in Germany with at least one showing in every Christmas season on TV.

It is against the background of this very high level of popularity of Sissi’s character that the team around Bremen’s head of opera, Frank Hilbrich, developed their take on the Kreisler operetta. They played with and against the knowledge of the operetta’s characters and events, and the expectations both of the subject matter and the genre of operetta they could assume their audiences to share. They did not consider it wise to double the feelgood aspects of the genre and the characters and plot. Instead, they cleverly and consistently juxtaposed references to the sugar-sweet sentimentality and very obvious elements completely at odds with that ideal world context. The set was painted on wooden and cloth backdrops, suggesting the ideal mountain world audiences would recognise and remember from the films; such memories were broken, however, in some of the intricate detail of those backdrops, where the scenery depicted on the left would be exactly the same as the scenery on the right! Panels in the wall, with parts of the landscape painted on them, would open suddenly, and close again, to serve as unrealistic entrances and exits for characters. As the operetta progressed, some of the cloth fell down, further disrupting the ideal-world impression.

The casting provided the team with the major factor for creating the constantly jarring effect working against the clichés of the ideal world: Sissi was played and sung by baritone Arvid Fagerfjäll, the Emperor was played by actress Lieke Hoppe. Mezzo-soprano Ulrike Mayer was Sissi’s father, Max of Bavaria, and bass-baritone Christoph Heinrich was Sissi’s mother, Ludovica. There were differences in the way those characters who had been cross-gender-cast were presented. Fagerfjäll and Hoppe sought to be as natural and close to the character’s gender as possible, while Mayer made it clear she was a woman relishing the time of being allowed to play a man. Heinrich played Ludovica in a style reminiscent of Charley’s Aunt. When Max tried to kiss his wife, Heinrich played hard to get with the words ‘Oh, I haven’t even shaved’. Helena and her love interest, the Count of Thurn und Taxis, were sung without recurrence to cross-gender casting by Elisa Birkenheier and Fabian Düberg.

In the films, there is one character who offers comic relief, Colonel Böckl; in the operetta, this character exists as well, here called Von Kempen, and in the Bremen production he was given ample of time and attention – and played by company stalwart Martin Baum. Susanne Schrader, another company stalwart, was very funny as the resolute Archduchess (contrary to the film, where the character is more sinister and threatening in her domineering nature). Their comedy added yet a further colour to that created by the cross-gender casting, funny aspects of the set, and frequent quotes by famous people (from Socrates to Woody Allen) thrown in to break the historical context.

The Bremen production supplemented Kreisler’s music, in the conventional operetta style of beautiful tunes and lots of sentiment, with five songs by Georg Kreisler (1922-2011), accompanied not by the orchestra but on the piano. For this, conductor Stefan Klingele was summoned from his position in front of the orchestra (placed at the back of the stage rather than in the pit) to sit at the piano. Both the songs themselves and the way they were integrated into the operetta added to the satirical edge.

Hilbrich’s major achievement was to keep the juxtaposition of those many elements, including the original music and text of the operetta, audience knowledge and related expectations, cross-gender casting, famous quotes, and the songs by Georg Kreisler in perfect balance and cogent order throughout. The production did not get close to, or let alone cross, the fine line towards anarchy and chaos.

Musically, under Klingele the orchestra brought out the lush operetta tunes with verve, while his piano accompaniment for the Georg Kreisler songs equally relished the difference in tone. The performers rose to the challenges admirably, taking on board and clearly comfortable with the cross-gender casting – the services of Heinrich Horwitz specifically for queer-dramaturgy will have helped here. As Sissi, Fagerfjäll’s voice was very flexible: gentle and soft where needed, but also able to rise to more steely passages. His breath control was excellent, allowing him to engage in long phrases as needed. Ulrike Mayer’s Max relished the funnily stereotypical Bavarian elements of her character, complementing much by way of Bavarian accent in her spoken passages with good and solid, hefty and hearty singing, to which her strong voice offered itself with considerable ease while maintaining vocal beauty. Elisa Birkenheier (Nené) and Fabian Düberg (The Prince of Thurn and Taxis) were the near-ideal young couple, as intended by both operetta and production. In their two duets, Birkenheier demonstrated her delightfully secure and shining coloratura, while Düberg displayed all the mellifluousness of the operetta tenor. Soprano Adèle Lorenzi played the ballet dancer and has impressive dancing skills, while her voice was particularly supple and rich in the lower register which dominates the music for her character.

Daniel Meyer-Dinkgräfe

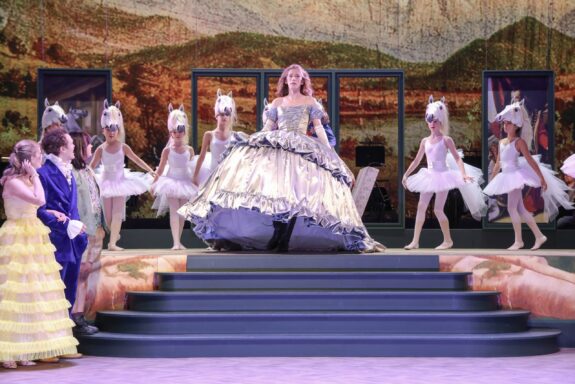

Featured Image: [l-r] Elisa Birkenheier (Nené), Fabian Düberg (The Prince of Thurn and Taxis) and Arvid Fagerfjäll (Sissi) © Jörg Landsberg

Production:

Director – Frank Hilbrich

Stage design – Volker Thiele

Costume design – Gabriele Rupprecht

Chorus director – Karl Bernewitz

Choreography – Jacqueline Davenport

Lighting design – Christian Kemmetmüller

Sound design – Charel Bourkel

Dramaturgy – Frederike Krüger

Queer Dramaturgy – Heinrich Horwitz

Cast:

Emperor Franz Joseph– Lieke Hoppe

Archduchess Sophie – Susanne Schrader

Duke Max of Bavaria – Ulrike Mayer

Ludovica – Christoph Heinrich

Helene, called Nené – Elisa Birkenheier

Elisabeth, called Sissi – Arvid Fagerfjäll

The Prince of Thurn and Taxis – Fabian Düberg

Colonel von Kempen – Martin Baum

Ilona Varady – Adèle Lorenzi

Pianist und Court conductor – Stefan Klingele

Siblings of Helene and Elisabeth – Bremen Theatre Children’s Chorus

Court Opera ballet – Students of Davenport Ballet School