United Kingdom Prom 34: Schubert, Dubugnon, Richard Strauss: Katia and Marielle Labèque (two pianos), BBC Symphony Orchestra, Semyon Bychkov (conductor), Royal Albert Hall, London, 8.8.2012 (CG)

United Kingdom Prom 34: Schubert, Dubugnon, Richard Strauss: Katia and Marielle Labèque (two pianos), BBC Symphony Orchestra, Semyon Bychkov (conductor), Royal Albert Hall, London, 8.8.2012 (CG)

Schubert: Symphony No. 8 in B Minor “Unfinished.” (1822)

Richard Dubugnon: Battlefield Concerto (2011) UK Première

Richard Strauss: Ein Heldenleben, Op. 40 (1897-1898)

The hot news is that Russian-born conductor, Semyon Bychkov has been appointed to a new position specially created for him by the BBC Symphony Orchestra. The Gunter Wand Conducting Chair has been chosen as Bychkov’s new title in recognition of the relationship the BBC Symphony Orchestra had with Wand when he was appointed Principal Guest conductor 30 years ago.

Bychkov and the orchestra already know each other well, and the new arrangement promises to be an exciting one. This evening we could look forward to a mixed programme spanning nearly two hundred years.

In the cavernous space of the Royal Albert Hall Schubert’s “Unfinished” began almost inaudibly; this was a shame because the opening cello and bass motif, and the restless string figures that follow it, form essential ingredients in the structure; it is essential to hear them! Resulting from this, the first woodwind entries felt a little too strong, but once things got underway we were on safer ground, and there was much to admire in the lyricism and drama of the movement. But there remained, overall, a tentative sense that did not help the musical flow. The same feeling of “holding back” characterised the second movement; again there was some beautiful playing from the woodwind, and this most perfect of Schubert’s creations affected us all over again with its touching simplicity and almost unbearable poignancy. Nevertheless some doubts remained; Bychkov’s sensitivity is commendable but does the music benefit from being quite as fragile as this?

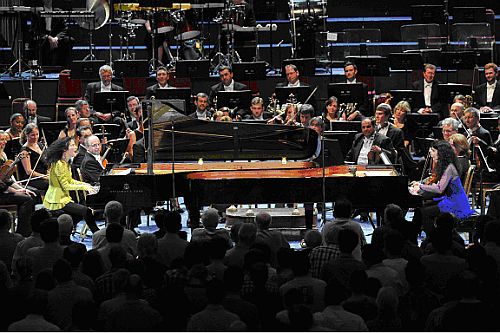

The platform then needed radical re-organisation. The French/Swiss composer Richard Dubugnon’s Battlefield Concerto, composed for tonight’s soloists, calls for an unusual orchestral layout, with the forces divided into two quite separate halves, although the overall instrumentation is that of a standard symphony orchestra with a few additions. One half, to the left, features high winds, and includes a bass guitar, the second, to the right, lower winds. Thus each pianist has her own orchestra; Dubugnon’s idea is that the two pianists and their orchestras face each other and do battle.

The composer’s starting point was a painting by the 15th century Florentine artist, Paolo Uccello entitled “Battaglia di San Romano.” Insofar as it follows the events of a make-believe battle, Dubugnon’s piece is programmatic and theatrical, and Dubugnon’s notes help you follow the battle’s events without too much difficulty; without them the work might have felt too rambling.

Balcony trumpet players, left and right, sound calls. During the next twenty-five minutes the two pianists announce their individual themes and elaborate on them widely, never joining with the same material until the very end. There are cadenzas, parades, battles, a funeral, a triumphal march, a peaceful section of reconciliation and finally a feast.

The piano and orchestral writing is often florid, flashy and fearfully difficult, with elements of, perhaps, Messiaen, Bartok, Ravel, jazz, rock – you name it. From that point of view it’s ideally suited to the Labèque sisters with their extraordinarily varied musical enthusiasms, and it’s highly entertaining in a fairly chaotic kind of way. The sisters tackled it with characteristic verve, with Bychkov, who is married to Marielle Labèque, marshalling his forces admirably. Hearing it a second time on BBC iPlayer, I made a lot more sense of the piece; ideas come and go continually, and the warlike nature of most of the music certainly comes across vividly, with more contemplative passages offering welcome relief. Whether the material really adds up I’m not so sure, and I will delve into it some more, but I worry that with so many influences clearly discernible the composer’s own personality is hard to pinpoint.

Ein Heldenleben, after the interval, was a real treat!

In an introductory talk on Radio 3, Bychkov reminded us that the proper translation of Ein Heldenleben is “A Heroic Life,” and not just “A Hero’s Life”; thus the sentiment behind the piece could be said to be that every life is heroic to some extent. Strauss was not merely thinking of himself, then, and although there are obviously autobiographical aspects, perhaps he sought a bigger picture. At the age of 51, Strauss was entering a new period in his creative life; the twentieth century had not yet begun, and he was still to write Electra. Yet in Ein Heldenleben Strauss looks forward to the new century, and one is struck by how much this work belongs to the 20th century rather than to the 19th with its huge orchestra, spectacular orchestration, daring harmonies, and operatic drama.

Bychkov was absolutely in his element here in a performance full of passion, excitement, and great beauty. The guest leader, Sergey Levitin, was well on top of the crucially important solo violin part, portraying the composer’s wife, Pauline, complete in all her myriad complexities. The second battle of the evening was terrifying, with marvellous brass and percussion work, and the subsequent tutti passage, in which Strauss remembers some of his past works, absolutely enthralling. If there were one or two rough edges, they certainly did not detract one bit from a performance which carried us through all six main sections and was choc-a-bloc with flair. Glorious!

Christopher Gunning