United Kingdom Orlando Gough/Richard Stilgoe, Road Rage (première),Garsington Community Opera, Southbank Sinfonia / Susanna Stranders (conductor), Garsington Opera Pavilion, Wormsley, 19.7.2013. (RJ)

United Kingdom Orlando Gough/Richard Stilgoe, Road Rage (première),Garsington Community Opera, Southbank Sinfonia / Susanna Stranders (conductor), Garsington Opera Pavilion, Wormsley, 19.7.2013. (RJ)

Cast:

Girl: Clare Presland

Surveyor: Alexander Byron Hargreaves

Minister: Daniel Norman

Activist: Peter Willcock

Kites: Juliet Dudley, Sophie Haxworth, Oliver Winter

Chorus of Trees (Stokenchurch Primary School)

Chorus of Animals (Chalgrove Community Primary School)

Chorus of Newts/Village Children (Ibstone Cof E Infant School)

Chorus of Political Advisors

Chorus of Slaves, Activists, Villagers

Production:

Director: Karen Gillingham

Assistant Director: Katherine Wilde

Vocal Director: Lea Cornthwaite

Designer: Rhiannon Newman Brown

Lighting Designer: Chris Vaughan

Producer: Kate Laughton

Whatever became of Richard Stilgoe? He’s the lyricist, songwriter and musician who wrote the libretti for musicals like Starlight Express, composed and performed countless witty topical songs, and even performed at Liverpool’s famous Cavern Club. But having lost track of him in recent years I assumed he was no longer with us. That only goes to show that I don’t move in the right circles. Sir Richard Henry Simpson Stilgoe, OBE, DL, (knighted last year and currently Deputy Lieutenant of Surrey) is very much alive and has just written a splendid new community opera – Road Rage. His collaborator, composer/conductor Orlando Gough, made an impact earlier this year at Glyndebourne with his new opera Imago (review).

Building roads, especially on a crowded island like Great Britain, has always provoked strong feelings, especially when the proposed route goes through one’s garden, as is the case with the Minister of Infrastructure in this work. Being a Minister, with an army of spin-doctors at his beck and call, he manages to deflect the route so that is goes through the village green of Trentfield Oldfield in his constituency instead. When the news is leaked, it provokes vehement protests from the villagers (except those who will benefit from generous compensation terms or are enthusiastic motorists!). They get backing from a group of professional activists who know their way around the law and show them that the way to get plans overturned is to play the endangered zoology, threatened biology or archaeology cards.

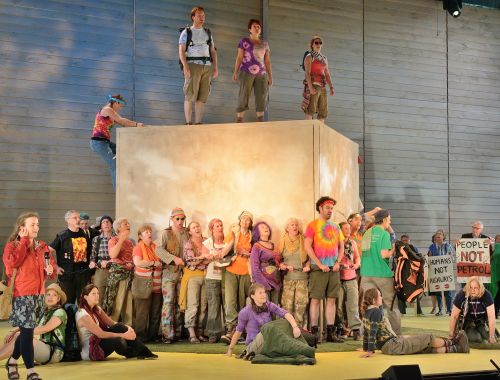

All this may sound boring and predictable, but it is actually very amusing and with its cast of 200 is something of a spectacle. The prologue is set in Roman Britain where Roman surveyors using the surveying equipment of the era mark out a new road and Roman centurions force British slaves to move a huge chalk cube for the construction of a new temple. Three hungry kites (birds of prey) swoop down on the slaves and send them scattering, with the result that the stone is left in the middle of the route of the new road…….where it remains until the present day on what has now become the village green where a chorus of trees and wild animals consider how time passes but “The stone stands still.”

Enter the surveyor with up-to-date technology who is confronted by a feisty young woman who discovers the plans for a road and appeals to the animals, trees and general public to protest. The kites are delighted. “Roadkill – Free meat on the street,” they exclaim. We also meet the Minister surrounded by his bespectacled advisers who are furious about the leakage. He chronicles his career to date from idealistic MP to professional politician in thrall to his officials in a song which bears a resemblance to Sir Joseph Porter’s in HMS Pinafore, except that Sir Joseph’s career is always upward, whereas the Minister’s goes from compromise to compromise.

A public meeting is convened in the village hall in which the locals insist in chorus: “The reason that we came here/Is that life stays the same here/And we will fight to stay the same.” Tension rises in the Ministry of Infrastructure as the spin doctors reprove their Minister, while the kites observe in wry amusement that “There’s bad karma on the village green” and resolve not to descend to the level of squabbling human beings. The action takes a leap forward with the arrival of some professional activists (hippies) who know exactly how to throw a spanner in the works of the government machine. There is what looks like the stirrings of romance between the surveyor and the feisty young woman, but all turns sour when contractors arrive on the scene to remove the chalk cube and he gives her away to the security people.

Just as it looks as if the village green is doomed, a sudden twist to the story (which I shall not reveal) sees the villagers, animals and trees celebrate together in a rousing final chorus: “There’s a green and pleasant land I know,/ A land that sings of long ago,/ A land where man is merely passing through/ The land is old and man is always new.” On this warm pleasant evening amid the lush scenery of the Wormsley Estate it was difficult not to go along with this sentiment.

Garsington is usually associated with professional opera performances for which even Seen and Heard reviewers dress up to the nines. But may I dare to suggest that this is the organisation’s greatest triumph so far? Although most of the cast were amateurs, this was a highly professional production with the music overseen by a formidable lady conductor. Clare Presland propelled the action along as the feisty young woman, and the hapless Daniel Norman brought to mind a number of politicians who are bowled along by events over which they have no control. His army of bespectacled advisers sent a shiver down the spine, and I felt I had more in common with the trees and the charming creatures of the wild. The three kites were high-fliers in more senses than one and the banner-carrying villagers looked and sounded REAL and performed with gusto.

Top marks are due to director Karen Gillingham for an imaginative and hassle-free production which really zoomed along. Rhiannon Newman Brown’s designs were excellent, particularly the costumes for the kites and the newts (I hope I haven’t given anything away!), but it was difficult to judge the lighting effects since the stage was bathed in evening sunlight. (I’m not complaining, though!). Orlando Gough’s music fitted the action well and was by no means a walk-over; part-singing was required even among the younger performers. As a satire on modern society Road Rage hit the mark and I shall look forward to Sir Richard’s next big project with interest.

Roger Jones