Faithful to his Own World: Gavin Dixon Meets Composer Alexander Raskatov

Alexander Raskatov is one of the leading Russian composers of his generation. He now lives in Paris, but the musical philosophies and traditions of his native land continue to define his work. The Orthodox faith guides much of his music, but informs a style with more focus and rigour than that of his “religious minimalist” contemporaries. He also has a playful side, his humour ranging from the sophisticated to the surreal.

Raskatov’s reputation in the West currently rests on a handful of large-scale projects, his 2007 performing edition of Schnittke’s Ninth Symphony and his 2010 opera A Dog’s Heart, which was premiered in Amsterdam – it was written to a Dutch National Opera commission – and has since been staged at English National Opera, La Scala and Lyon. One of the more surprising aspects of Raskatov’s recent career has been his repeated appearances in County Louth, Ireland. The Louth Contemporary Music Society, under the directorship of Eamonn Quinn, has rescued an “orphaned” Raskatov score from obscurity, Monk’s Music for string quartet and bass singer (2005). The premiere was given by LCMS in Dundalk in 2013, followed by a commercial recording (LCMS 1302). In May 2014, a second performance was organised as part of the Drogheda Festival. Raskatov and the soprano Elena Vassilieva also performed some of his works in the concert.

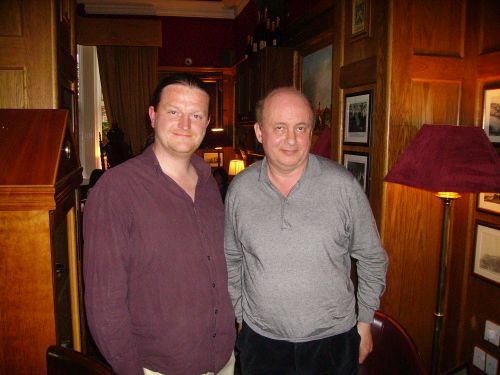

Meeting up with Sasha (as he’s universally known) earlier that afternoon was a fascinating experience. He’s a friendly and talkative man, happy to discuss his music at length, but equally interested in other people’s perspectives on his work. He speaks fluent English, and when a word escapes him, he can always find a viable alternative from French.

The first work on the programme, the song cycle To Those Who Have Been Healed dates from 1980, towards the end of his studies. “I was very young,” he remembers. “When you are young everything is in front of you, and I remember my enthusiasm. When you begin something for yourself for the first time, it’s important.” The cycle isn’t typical of Raskatov’s later work, particularly the harmonies, which are unusually astringent. For him, though, revisiting this early score has highlighted some continuities. “It seems to me there are roots in my style, common sources. Now I understand that this cycle contains, in its second movement, a rhythm that formed the basis of A Dog’s Heart. I realise now that the entire opera came actually from this forgotten cycle. It took only 30 years and I remembered.” So has he evolved as a composer in those years? “Yes and no. I hope that, like everybody I follow a certain evolution, but on the other hand there is a certain constant that stays, otherwise the composer has no colonna vertebrale.”

The second work, Recordare (2006), also has links with one of Raskatov’s larger projects, his 2007 performing edition of Schnittke’s Ninth Symphony. The symphony had a tortuous path to the concert stage. Schnittke completed the work, but as a result of his illness – following a stroke he had taught himself to write with his left hand – the manuscript was all but indecipherable. Several other composers tried to make sense of the music, but without success. Eventually, Schnittke’s widow, Irina, approached Raskatov, who achieved the impossible, bringing the music to life in a spirit fully conversant with Schnittke’s elusive late style. Recordare a short solo piano work, dates from the same time and is dedicated to Irina. “During this period I became great friends with her” says Sasha, “I had known her for years, but when I worked on the Ninth Symphony we came much closer, and I decided to write a short piece for her. I also wrote it as a remembrance of the music of her husband. The title, Recordare, is like a kind of shadow of Schnittke himself. The music includes rhythms and ideas that are typical of him, particularly a kind of old Russian church motive transformed through specific harmonies to create a kind of eternal lullaby. It is a very simple piece and the end imagines Russian church bells – a kind of nostalgia for the composer.”

For anybody looking for a handle on Räskatov’s music, the influence of Schnittke is a useful starting point. Like Schnittke, Raskatov writes religious music, but which retains an intellectual rigour. He’s also not averse to humour and stylistic juxtaposition in his work. Raskatov’s music is not polystylistic as such, but Schnittke has clearly demonstrated a path for him. A Dog’s Heart in particular seems to have inherited much from Schnittke’s anarchic scores of the 1970s. So how, I wonder, would Raskatov respond to the label “postmodern”, so often applied to Schnittke’s music?

“I’m against such labels. We are not just butterflies to be pinned onto a board. Sometimes I think it might be easier to survive if I did classify myself, because unfortunately the music world now seems to me like an enormous supermarket. You know where to buy soap or pepper or matches, but if there is a kind of goods which you don’t know what it is, very good quality, but you don’t know the name, you don’t buy it. It is the same with the classification of composers. It’s easy to be minimalist, or post-serialist, or primitivist, or whatever. And today it has become important because the quantity of musical information has become enormous. Composers have so much information to digest. There are so many musics which sometimes totally contradict each other. It provokes enormous aggression between composers from different groups, which is not my cup of tea. I think we have to be tolerant. I came from the Soviet Union – I know what it is to be intolerant. We have to be tolerant to music of different spectra. If it is of a professionally high level, we have to except that it can exist.”

“But opera is a very special genre. It is a kind of polyphonic genre in the sense that a lot of different styles, a lot of different events, are possible. I think it is impossible to write if you are too much of a purist. In real opera, you have to admit everything that helps to create drama or interest; it’s a genre of communication with the public. You can choose what you want according to the goal, according to the subject. In A Dog’s Heart I used a lot of things for which people will probably hate me. But I don’t care – I was free. The most important thing in opera is to forget about the limits imposed by other composers; that will give you bad energy. This, I think, is one of the reasons why my opera is still alive.”

It’s very Russian music too, and on a distinctively Russian subject – a satirical novel by Bulgakov. Yet it was written in France and premiered in Holland. I wonder if the experience of exile has informed Raskatov’s work – made it sound more Russian perhaps? Although Raskatov does not directly address such issues in his music – a significant difference with Schnittke – he is keenly aware of the unusual situation he is in. When I raise the subject, Raskatov turns the conversation round to the circumstances of his departure.

“The 1990s were very difficult for me, and also for my colleagues, in all senses, not only in the sense of music, but also of health, of security, physical and mental, and in the sense of just surviving. I left Russia in 1994. But to tell the truth, I don’t know anybody who would leave his country for no reason. There are always certain grounds and sometimes not very positive grounds, otherwise it would be normal to live in your own country, to be born and to die there.”

“The problems were worst for the younger generation of composers. They were lost, because they didn’t know what to write. Everything was possible, therefore nothing was possible. All the limits imposed by the ideology – I can’t say they were positive, I’m not a reactionary – but they produced composers like Schnittke, produced many kinds of resistance. When somebody beats you, you want to do something as a response. Action creates counteraction. That is what we had in the 70s and 80s, music as a reaction against the ideology. But then it ends and suddenly you don’t know what to do. Think of Shostakovich after the death of Stalin. Even with his genius, he was lost for a time. He had lost an enemy who had always been in dialogue with him.”

So what was Raskatov’s solution? “My solution is to be faithful to my own world. Many young Russian composers in the 1990s took a different path. Russia became an extremely poor country, and they thought that if they could imitate the music of the West, where commissions seemed plentiful, it would yield dividends. But they ended up with a copy of a copy. I chose a different route. Music that conforms to a “school” can easily become extremely dogmatic. In the Soviet Union, a dogma was imposed by the leadership of the Union of Composers, but similar dogmas exist in the West. They have other names and impose other styles, but they still exist. Our sudden freedom was not very fruitful from the point of view of the final result.”

The main work in the Drogheda concert, Monk’s Music, carries a dedication to Mieczysław Weinberg, a composer whose stock has risen considerably in recent years, even if it has taken several decades since his death for his music to be properly appreciated.

“We were friends. When I was young, from around 1980, I often visited Weinberg. He invited me. He played me his music, I played him mine. We talked a lot. It was a fantastic time, and I thought it would never end. He played an important role because he always supported my music in all the Moscow institutions, the Union of Composers, the Ministry of Culture and so on. He was old school, full of old traditions. He had played four hands with Shostakovich, and he told me many things about his friendship with Shostakovich. But he was an extremely modest man. I came to him with my early Viola Concerto, which I had dedicated to him – I’d written the dedication in very grand, self-important language; I was young. I played it for him and he was very touched. He said: ‘you know Sasha this is the third composition which is dedicated to me’ I asked what the first two were, he said: ‘the Tenth Quartet of Dmitri Dmitriyevich [Shostakovich] and then the Cello Sonata of Boris Tchaikovsky; and now you are the third one.’ Anyway, during the 80s we met dozens of times. I helped him to organise the recording of his opera Portrait. We always had a lot of things to discuss.”

Listening to Raskatov talk about Weinberg’s final years, it’s clear his neglect was keenly felt.

“When I left Russia, my departure was probably provoked by his illness. In 1993 I came to his house. He was very, very ill – he was dying really in poverty. He wasn’t able to buy important medicines for his treatment. It all cost money, and our Union of Composers, our government was unable to help him. I spoke to Elena Vassilieva about this composer who was so ill, and she sent some money. She told me to just give it, from one French singer to a composer, it might help a little bit. And I came to him and I told him I had some money for him. And he asked: ‘Sasha, is it your money?’ I said: ‘No, it is not mine, just take it.’ And he cried. When I saw this I thought, if this composer, who wrote so many symphonies, quartets, and operas, is in such a helpless situation, and the country cannot do anything for him, what can there be here for us younger composers? So it was something very painful that I felt. He never knew it, but that was a turning point for me. It showed me the real situation of music in the 1990s. I left and soon after he died. I received a letter from his wife. I regret very much that I left without saying adieu. And I felt that I was obliged to somehow commemorate his existence, to dedicate something to him. And as he was a great master of string quartets I decided this genre would be the best for his memory.”

Talking about Weinberg’s last years leads us on to a discussion about fame and success, how composers often are celebrated in their lifetimes but then soon forgotten, or, as in the case of Weinberg, only fully appreciated after they die. Weinberg died, Raskatov tells me, thinking it had all been in vain, that nobody would ever hear his music again – quite an irony considering the huge surge of interest in every aspect of his work over the last decade. And sadly, Weinberg’s case is far from unique. “Fate plays strange jokes with composers”, Sasha ruefully concludes.

Returning to the present day – what is Raskatov working on at the moment? “I am working on a project – people don’t say composition any more, they say project, it’s very modern – a project called GreenMass. It is a commission from the London Philharmonic Orchestra with Vladimir Jurowski. It will be based on the traditional Catholic Mass in Latin, with other texts added, in five different languages, dedicated to the beauty of nature; hence Green Mass. I am from Russia, a land of forests and fields, and I really miss it, the space. Also, I think we have done very bad things to our nature. I don’t belong to the Green Party, but if I were to chose, I would choose this one, because we all have a responsibility for what we will leave the next generation, and that’s a real problem. That’s why I combined Latin texts with secular texts about nature. There are some other projects, smaller ones, but this is the most important for me at the moment. Of course I hope that A Dog’s Heart won’t remain my only opera. I have some ideas about others, but we shall see how they develop.”

Gavin Dixon