United States Lin Hwai-min, Rice: Cloud Gate Dance Theatre of Taiwan, Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, Los Angeles, 29.1-2016-31.1.2016. (JRo)

United States Lin Hwai-min, Rice: Cloud Gate Dance Theatre of Taiwan, Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, Los Angeles, 29.1-2016-31.1.2016. (JRo)

Dancers:

Chou Chang-ning, Huang Pei-hua, Tsai Ming-yuan, Huang Mei-ya, Ko Wan-chun, Liu Hui-ling, Su I-ping, Yang I-chun, Hou Tang-li, Lee Tzu-chun, Lin Hsin-fang, Wong Lap-cheong, Chen Mu-han, Kuo Tzu-wei, Wang Po-nien, Yeh Yi-ping, Chen Tsung-chiao, Chou Chen-yeh, Cheng Hsi-ling, Fan Chia-hsuan, Huang Li-chieh, Huang Lu-kai

Production:

Choreography: Lin Hwai-min

Music: Hakka traditional folk songs, drum music by Liang Chun-mei, Monochrome II by Ishii Maki, “Casta Diva” by Vincenzo Bellini, Le Rossignol et la Rose by Camille Saint-Saëns, Symphony No. 3 in D Minor, Fourth Movement, by Gustav Mahler

Set Design: Lin Keh-hua

Lighting: Lulu W.L. Lee

Projection Design: Ethan Wang

Videographer: Chang Hao-jan (Howell)

Costumes: Ann Yu Chien, Li-Ting Huang

Before a video backdrop of ever-changing cycles in the cultivation of rice – flooding, sprouting, harvesting, and burning – the superb dancers of Cloud Gate Dance Theatre of Taiwan enact a drama of life, death, and rebirth. Combining the idioms of ballet, modern dance, Qi Gong, and internal martial arts, Lin Hwai-min, artistic director of Cloud Gate, has created a dance vocabulary that is both primal and elegant.

Rice was inspired by the renewal of rice fields destroyed by chemical fertilizer in the East Rift Valley of Taiwan. Through organic farming, this area, formerly known as the Land of the Emperor’s Rice, was restored. Sections of the dance, entitled Soil, Wind, Pollen, Sunlight, Grain, Fire, and Water, take us on a journey of perseverance in the face of disaster – an acknowledgement of man’s fragility in a threatening universe. What we take away from the experience is an ode to the human spirit in dance, music, and visual art.

In postures reminiscent of Martha Graham, the opening movement, “Soil,” gave us women in deep knee bends rising on their toes, then stamping down on their heels. They audibly inhaled as they rose, followed by the percussive rhythm of feet hitting the floor. As they moved from their positions on stage into a central mass they became one organism gasping for its last breath or, perhaps, learning to breathe. Behind them, no higher than a doorway and the length of the stage, a projection of mud and water added to the disquiet.

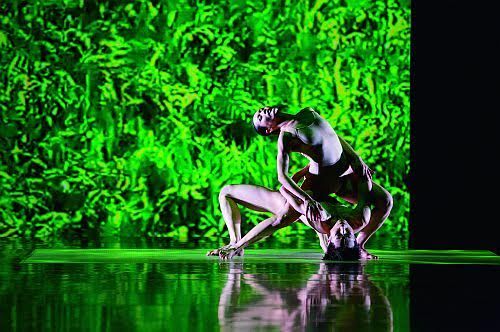

To drums and the sound of wind, dancers were tossed and jostled as images of vivid green rice leaves waved behind them, creating a sense of expectancy. Then, in a stirring sequence, we were presented with “Pollen II” and what was a true interpretation of the act of sex enacted in choreographic terms. In front of a compressed backdrop of green, two dancers intertwined their limbs, rotated their torsos, and clung to one another as light and shadow flickered across their bodies. The effect was primal, sensual, and joyful all at once.

An amalgam of music – drums, Hakka (ethnic Taiwanese) folk song, and Western opera and symphonic music – wove a spell and flowed seamlessly. Saint-Saëns’ otherworldly Le Rossignol et la Rose, conjuring a nightingale in song, added a primordial quality to the pas-de-deux of “Pollen II.”

The beauty of the dancing can be attributed to the extraordinary precision of the movements coupled with a gracefulness growing out of deep experience rather than relying on superficial prettiness. Women’s limbs transitioned from soft expressiveness to sharp angles. An elegantly pointed foot suddenly turned inward, reminding us that perfection is fleeting.

Male dancers carried themselves like danseur nobles at one moment, then like fierce martial arts fighters the next. Wielding long wooden staffs in “Fire,” they beat the floor and shook the sticks defiantly in the air, moving purposefully in what felt like ritualistic dance patterns. As smoke was depicted in the visual field of the backdrop, dancers converged center stage to form a silhouette of mass and line in front of the smoky white video projection. It was for a moment only but that brief pose carried with it both subtlety and power. The same could be said of the entire seventy minutes of Rice.

Jane Rosenberg