United States Philip Miller, Refuse the Hour: Various soloists, performers and musicians / Adam Howard (conductor), UCLA’s Center for the Art of Performance at Royce Hall, Los Angeles, 18.11.2017. (JRo)

United States Philip Miller, Refuse the Hour: Various soloists, performers and musicians / Adam Howard (conductor), UCLA’s Center for the Art of Performance at Royce Hall, Los Angeles, 18.11.2017. (JRo)

Cast:

Artist – William Kentridge

Dancer – Dada Masilo

Vocalist – Ann Masina

Performer/vocalist – Joanna Dudley

Actor – Thato Motlhaolwa

Musicians: Adam Howard, Tlale Makhene, Waldo Alexander, Dan Selsick, Vincenzo Pawquariello, Thobeka Thukane

Production:

Conception and libretto – William Kentridge

Choreography – Dada Masilo

Video Design – Catherine Meyburgh and William Kentridge

Dramaturgy – Peter Galison

Scenic Design – Sabine Theunissen

Costume Design – Greta Goiris

Lighting Design – Felice Ross

Movement – Luc de Wit

Expectations run high when one sees an opera staged by William Kentridge, the prolific South African artist. With his formidable skills as draughtsman, animator and director, he crafts a grab bag of imagery as effortlessly as a magician drawing a rabbit out of a hat. And therein lies both Kentridge’s strength and his weakness: his work, though visually dazzling, often suffers from an excess of content. The eye, bouncing from one effect to the next, has no place to settle as it is bombarded by Kentridge’s mix of line, collage, film and performers; consequently, the ear has trouble focusing on the music.

This was evident in the Metropolitan Opera’s productions of Shostakovich’s The Nose and Berg’s Lulu. Happily, with its smaller scale and more humble classification as a chamber opera, Refuse the Hour avoids the trap that Kentridge’s large-scale work falls into. Neither the music by Philip Miller, his longtime collaborator, nor Dada Masilo’s striking choreography and dancing were swallowed by Kentridge’s video design, sets or costumes. All worked gleefully together to create the experience of a Dadaist universe presided over by the professorial Mr. Kentridge.

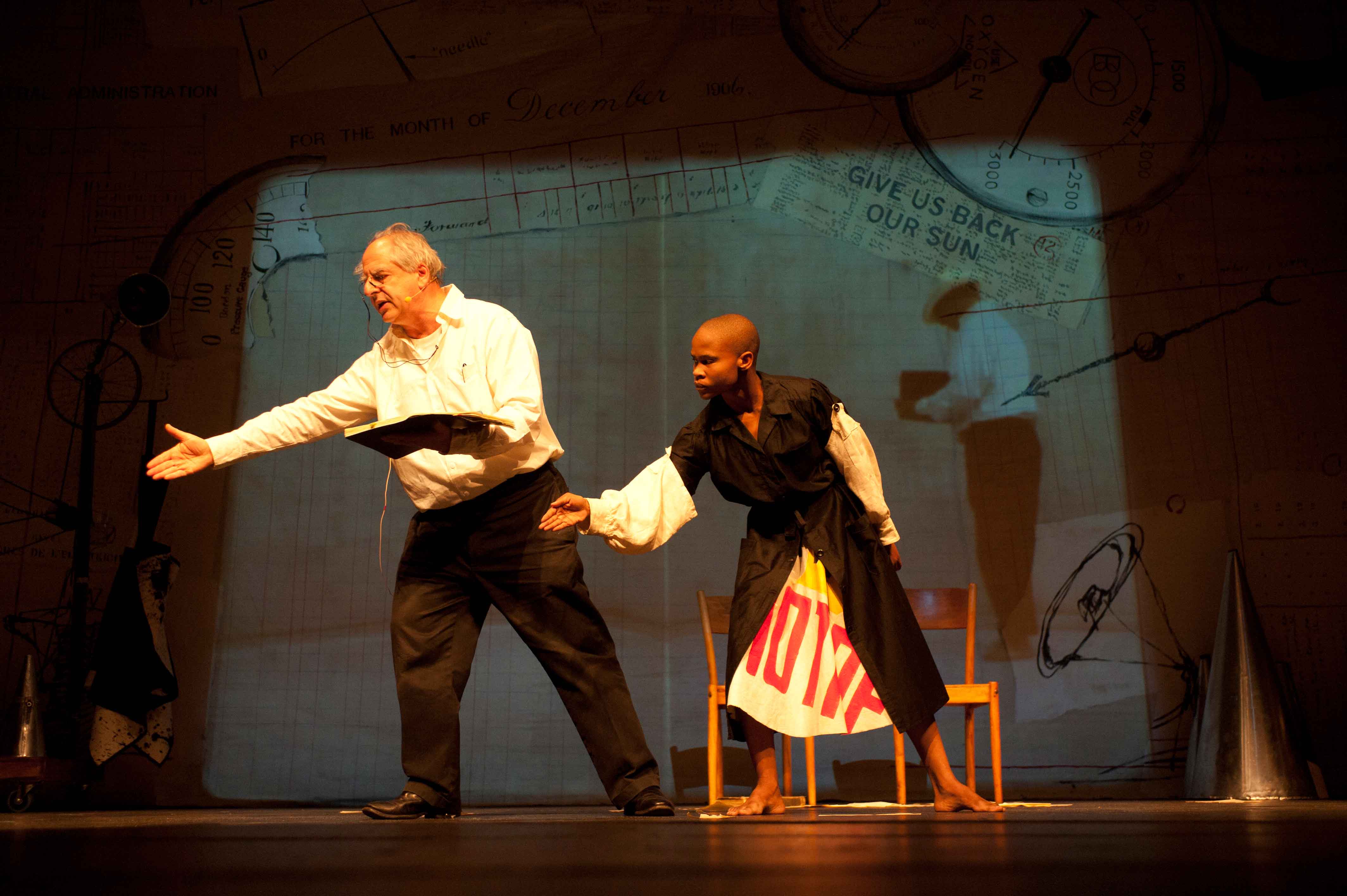

Lecturing to the audience, Kentridge assumed the role of narrator, storyteller, teacher and ringmaster, as instrumentalists, dancers and singers performed in front of a backdrop on which the artist’s thoughts and imagery were projected. The stage was crowded with Rube Goldberg-like musical machines, one more fanciful than the next. Everything, from the Perseus myth to the second law of thermodynamics to the rigidity of Western timekeeping inflicted upon colonial societies, was dissected and offered up as windows into the relativistic nature of time.

There was an upbeat atmosphere to the production – a kind of cabaret of scientific properties. It put me in mind of the Cabaret Voltaire, the Dadaist cafe in Zurich established by artists-in-exile during the First World War. This was clearly intentional as Kentridge references art movements of the past in all his work, whether art installation, film, painting or opera. Russian Constructivist illusions ran rampant in The Nose, a Dada ethos pervaded Lulu, and the Bauhaus artist Oskar Schlemmer was invoked in Refuse the Hour. When Masilo performed a haunting dance with silver megaphones encasing her limbs, Schlemmer’s Triadic Ballet was beautifully recycled and transformed into a Kentridge/Masilo dance of time.

Miller’s music had a wispy, ethereal quality, ranging from classical to carnivalesque. Ana Masina sang the Berlioz aria ‘Spectre de la Rose’, while Joanna Dudley vocalized snippets of otherworldly sounds, snatching them from pieces of Masina’s song or catching them from the air and expelling them through her vocal chords. An ensemble of six musicians performed onstage, often joining in the theatrical hijinks. Projected imagery behind the performers – whether of clocks, barometers, metronomes, words or windmill-like contraptions – added to the pandemonium but never overpowered the onstage action, a feat in itself. However, a filmed sequence in a tiny house of Masilo welcoming her husband home was such an engaging riff on Charlie Chaplin and Paulette Godard in Modern Times that it absorbed all attention away from the stage, which fortunately was quiet at the time.

Costumes with graphic shapes and bold letters emblazoned on skirts were imaginative and effective, but I would have preferred Kentridge’s own attire to be more consistent with the other performers. In standard-issue white shirt and black pants, he remained the artist outside the action giving a lecture demonstration, and at times it felt like the production might work better in a museum gallery or other site-specific location, rather than in a conventional theatre. This touches on another problem with the concept: one often felt at a remove from an immersive theatrical experience by dint of Kentridge’s lecture presentation. Unlike Robert Wilson and Philip Glass’s Einstein on the Beach, which also deals with time as subject matter but allows the imagery and music to speak for itself, Kentridge explains and explains, often verging on monotony.

Trading in nostalgia, Kentridge, with his art historical references, antique-style fantasy machines and homage to silent film, never takes a leap into the future as Wilson and Glass did. He was perhaps at his strongest when confronting colonialism and its consequences. In the most emotionally potent and involving scenes, entitled ‘Give Us Back Our Sun’, the geography of colonialism was exposed and explored, demonstrating how the imposition of Western standardized time assisted in enslaving Africa. Masina sang an aria that put me in mind of Kurt Weil’s great anti-apartheid musical, Lost in the Stars. Singing with force and conviction, she led the production to a higher level of involvement, reaching true dramatic heights.

Jane Rosenberg