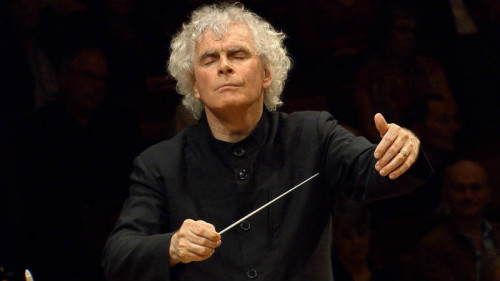

United Kingdom Tippett and Mahler: London Symphony Orchestra / Sir Simon Rattle (conductor). Barbican Hall, London 22.4.2018. (JPr)

United Kingdom Tippett and Mahler: London Symphony Orchestra / Sir Simon Rattle (conductor). Barbican Hall, London 22.4.2018. (JPr)

Tippett – The Rose Lake

Mahler – Symphony No.10 (performing version by Deryck Cooke)

At one point in Hans Christian Andersen’s famous tale (Keiserens Nye Klæder) about the Emperor’s non-existent new clothes his fawning acolytes exclaim ‘That pattern, so perfect! Those colours, so suitable! It is a magnificent outfit.’ After Tippett’s The Rose Lake all I heard around me from admirers of Tippett’s music were sentences with ‘wonderful’, ‘colours’, or even, ‘wonderful colours’ in them. It at least proves that there is nothing that new in new music as the modern obsession with percussion dates back at least as far as this final work from Tippett who at the time was Britain’s ‘greatest living composer’. The Rose Lake is described as ‘a song without words for orchestra’ and requires – Oliver Soden’s programme note told us – ‘a large orchestra, rarely heard together, but divided into soloists and chamber ensembles. There is an extensive battery of percussion, including two tam-tams, a gong and tubular bells … And most clear to an audience at a live performance is the array of rototoms: drums tuned to a specific pitch by rotating the head. Invented in the late 60s, less cumbersome and with a lighter sound than timpani, they were soon beloved of pop groups such as Pink Floyd.’ To be honest I was surprised how little they were actually used in the 30 minutes of The Rose Lake.

Tippett took his inspiration from Senegal’s Lake Retba which in bright sunlight can look pink because of some algae it contains. It was premiered by the London Symphony Orchestra in 1995 when the composer was 90. From the way the members of the orchestra were staring at the notes on their music stands Tippett’s music is undoubtedly a different soundworld compared to their usual concert fayre. There was much to admire in the commitment and technical accomplishment of the huge ensemble under Sir Simon Rattle – also with his head in the score – when playing the notes. However, their joint unfamiliarity with The Rose Lake did not seem to leave an option for ‘interpretation’. From the episodic ‘stop-start’ music I am surprised I ‘heard’ as much of Lake Retba as I thought I did. There is a primal-sounding opening before six Wagnerian horns usher in a Das Rheingold-inspired passage and the piece seems to become a series of loose variations on this theme with alternating periods of turbulence or calm. The music reaches a climax of sorts with a homage to Mahler in a beguiling surge by the LSO’s full strings. Perhaps as the light fades and the effect on the lake is no more, the music ends with an inscrutable grunt – marked as a ‘plop’ in the score – from the brass. With respect to Tippett devotees I would not willingly hear The Rose Lake again, though I suspect that says more about me than it does about them, or the music itself!

After hearing Deryck Cooke’s ‘performing version’ of Mahler’s Tenth Symphony over a period of time some years ago I came to the realisation that I did not really appreciate it as unquestioningly as his other works. Most know how Mahler left the first and third movements almost fully orchestrated and rest notated in short score. This makes any completion or ‘performing version’ pure guess work and potentially far removed from what Mahler would want us to hear. The version by Deryck Cooke, Berthold Goldschmidt and the Matthews brothers retains much of the economy of orchestration and clarity of ideas from the material Mahler left us and lets us experience what stage his composition had reached by the time of his premature death. However, theirs might not be the only answer and since the world could do with as much of Mahler’s music as is possible, it might be worth giving an occasional outing to the other attempts – including by Clinton Carpenter, Remo Mazzetti Jr, Joseph Wheeler and, most recently, Yoel Gamzou – to see if they have anything to say to us.

This might be something of a moot point because Rattle has championed Cooke’s version since the 1980s and was able to make it sound more coherent, evocative and engrossing than any previous performance I can remember. The Tenth Symphony takes us on a harrowing journey from despair to a final, positive – though extremely fragile – resolution. This symphony clearly demands a great conductor and an equally great orchestra to bring it off successfully and there can be few better partnerships – in this repertoire – than Rattle and the LSO.

The Tenth Symphony has a neat – oddly symmetrical – structure with the two outer movements being long and slow and bookending two shorter scherzos with the even shorter Purgatorio between them. When composing this symphony Mahler seems to have guessed that his time with Alma, as well as, his life was coming to an end. He seems to be alternatively attempting to stop the inevitable or bemoaning his lot throughout its alternating bouts of stoicism, despair or vitality. It seems to begin and end with apotheoses and I have commented before how the opening Adagio seems to be a danse macabre suffused with a sense of inconsolable grief. The shrieking dissonant cluster chords near the end of the first movement are a visceral cry of despair – possibly the discovery of Alma’s affair with Gropius in music – which ushers in an epilogue of consolation for the strings. Rarely do the LSO’s string section sound as good as they do under Rattle.

The metre of the first Scherzo seems to change with almost every bar and soon we hear a graceful Ländler as a – possibly naïve – reminiscence of earlier happier times. The pivotal short third movement was eerie and agonising. Conducting without a score, Rattle’s interpretation got better and better with the angst of the second Scherzo leading directly into the Finale‘s apocalyptic drum-strokes. We had probably heard another danse macabre and I must remind readers here of the note Mahler wrote at this point in the score: ‘Der Teufel tanzt es mit mir’ (The Devil dances is it with me) and below the muffled drumbeats – the memory of a funeral procession he and Alma had heard in New York – Mahler scrawled ‘Du allein weisst was es bedeutet’ (You alone knows what it means). In 2018 those in a marriage like theirs would be undergoing couples counselling! The trajectory towards the final bittersweet conclusion was managed by Rattle with an instinctive feel for the symphony’s harrowing and spare musical language. On the last page, ‘Für dich leben! für dich sterben! Almschi!’ (To live for you! To die for you! Alma!) is seen. There is one final passionate outburst, and we experience the intense yearning for the loss of both love and life before the music resignedly dies away.

Overall, it was a thought-provoking, emotionally engaging and memorable performance. Throughout the LSO responded to Rattle’s encouragement with playing of raw energy but redolent of eloquence and refinement. Among the many virtuosic contributions; Gareth Davies’s flute, David Elton’s trumpet and the leader Roman Simovic were the best of the best.

Finally, I would like to leave readers with a further thought about this concert of ‘last works’. Tippett’s infirmity meant that The Rose Lake was dictated to – near namesake – Michael Tillett and, of course, we owe the Tenth Symphony mostly to Deryck Cooke. So you have to wonder just how much of what we heard was Tillett and Cooke rather than Tippett and Mahler?

Jim Pritchard

For more about the LSO click here.