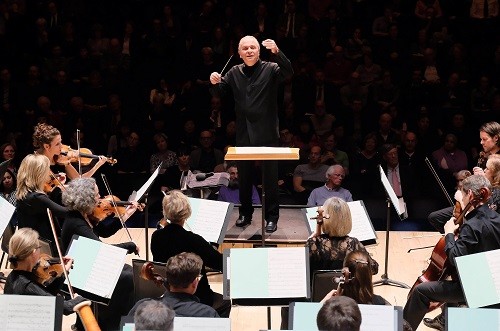

United Kingdom Britten, Mahler, and Brahms: Paula Murrihy (mezzo-soprano), Britten Sinfonia / Sir Mark Elder (conductor). Saffron Hall, Saffron Walden, Essex. 18.1.2019. (JPr)

United Kingdom Britten, Mahler, and Brahms: Paula Murrihy (mezzo-soprano), Britten Sinfonia / Sir Mark Elder (conductor). Saffron Hall, Saffron Walden, Essex. 18.1.2019. (JPr)

Britten – Suite on English Folk Tunes

Mahler – Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen

Brahms – Symphony No.2 in D major

As I wrote last year (review click here) the Britten Sinfonia was founded in 1992 and inspired ‘by the ethos of Benjamin Britten through world-class performances, illuminating and distinctive programmes where old meets new, and a deep commitment to bringing outstanding music to both the world’s finest concert halls and the local community.’ Britten Sinfonia has no permanent principal conductor or director and chooses to work with suitable guest artists from across the musical spectrum for each particular project. This concert followed one the night before in the Barbican Hall and was destined to end the next evening in Norwich. It was interesting to hear from Sir Mark Elder in a wide-ranging and absorbing pre-concert talk how rehearsals had only begun at the start of the week. This concert was broadcast live on BBC Radio 3 and can be heard for 30 days on BBC Sounds where you will have the benefit of Elder’s pithy introductions to the music as we in the audience did.

The Britten Sinfonia’s were continuing their first Brahms cycle and the first Elder has conducted. Each concert has the succeeding symphony with – as here – Mahler Lieder and lesser-known works from 20th-century English repertoire. Eventually the plan is to play all four symphonies together in a short space of time.

Benjamin Britten composed his Suite on English Folk Tunes: A Time There Was in 1974, just two years before his death, and a short time after a partial recovery from heart surgery and a stroke. It is a strange coincidence that Britten was plagued by a heart condition in much the same way as Mahler, a composer whose music Britten did so much to champion. This late work is dedicated to Percy Grainger and each of its five brief parts is based on an English folk song and there is a wide range of moods. The percussion launched ‘Cakes and ale’ as a jaunty – yet slightly sinister – march; ‘The bitter withy’ was more wistful with hints of Vaughan Williams; ‘Hankin Booby’ for woodwind (recalling sackbuts) and drum was composed for the 1967 opening of the Queen Elizabeth Hall and sounded suitably Elizabethan; ‘Hunt the Squirrel’ was a full-on jig; the key to the work’s title is that it comes from Thomas Hardy’s Before Life and After and the elegiac tone of ‘Lord Melbourne’ – emphasised by Emma Fielding’s plaintive cor anglais – brought Debussy to mind, whilst a plaintive horn solo ushered in a reflective close. Naturally the Britten Sinfonia exhibited a peerless command of the composer’s music.

My mantra has long been that Mahler’s Lieder are fundamentally ‘operatic’ although many still consider the ‘Art’ of the singer should be to internalise each song and keep their emotions in check. It helps my cause when they are accompanied by an orchestra and the conductor is someone with the opera experience of Sir Mark Elder. Mahler’s youthful cycle ‘Songs of a Wayfarer’ – written before his symphonies and other large pieces – explores the conflicting emotions of an abandoned lover. Inspired by a collection of German folk poetry, Des Knaben Wunderhorn, the 24-year-old Mahler wrote his own texts and composed Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen whilst infatuated with Johanna Richter (a piano pupil of his, as well as, a singer).

As a very late replacement for the advertised singer, mezzo-soprano Paula Murrihy had an expressive face and voice and coloured the songs with myriad shadings and details. There was a heart-aching vulnerability to ‘Wenn mein Schatz Hochzeit macht’ as a beloved’s wedding to someone else is recounted and ‘Denk ich an mein Leide!’ (‘I think of my sorrow’) at the end was deeply poignant. ‘Ging heut’ morgen über’s Feld’ (‘I walked through the field this morning’ juxtaposed nature’s wonders with a sorrowful ending underscored by touching beauty from the Britten Sinfonia. Murrihy’s ‘O weh!’ (‘O woe!’) moan in ‘Ich hab’ ein glühend Messer’ (‘I have a glowing knife’) was clearly ‘operatic’ and there was the psychopathic fervour to her singing that this song needs. The final moments were chilling and the chamber-like poetry from the virtuosic players was sheer perfection. In the final song, Elder’s funeral march orchestral accompaniment was as profound as Murrihy’s controlled singing. The very last lines she sang revealed the impressive range of her high mezzo as it descended in deep resignation from ‘alles’ (everything) to ‘Traum’ (dream) during ‘Alles! Alles! Lieb und Leid, und Welt und Traum!’.

In his pre-concert talk Elder discussed Brahms’s high-pitched voice and his misspent youth in the brothels of Hamburg, and it took a while for this to leave my mind as I encountered his Second Symphony for the first time! Elder also discussed the horn playing at some length and their use, along with the trombones, of smaller bore instruments. This allowed for a different balance between the brass and the rest of an orchestra considerably smaller in size than is sometimes used for this symphony. Elder clearly got the posthorn effect he was looking for at the start of the first movement. Jo Kirkbride’s programme note reminds us how ‘Brahms teased his publisher. “I have never written anything so sad, and the score must come out of mourning.” This could hardly have been further from the truth. Where the First Symphony is dark, gloomy and at times even unwieldly, the Second radiates lightness and warmth, from the cheerful bucolic wind calls of the opening movement to the glorious, unbridled joy of the last.’

Navigating the great stretches of the first movement – that has some surprising Wagnerian sounding moments – clearly needed a firm hand to avoid them sounding episodic, and that is what Elder brought to it here. The Britten Sinfonia’s strings excelled in the second movement with a very musically-played horn solo by Alex Wide. Elder dwelt on some of the symphony’s more serious Adagio elements here before launching into its undoubtedly more cheerful second half. The third movement, oozed Gemütlichkeit and with its dance-like rhythms thoughts turned to Dvořák (perhaps not for the first or last time in this work). Elder said that approaching this music afresh with smaller forces can give an opportunity to stop and smell the (musical) roses and that he certainly did on occasions in the first three movements. However, the Allegro con spirito finale went helter-skelter and was the very spirited highlight of the entire concert. Elder drove his willing musicians on and a blaze of brass – which given their head could have been very Brucknerian – ushered in a palpably joyous and triumphant conclusion. A fitting end to an evening of great music.

Jim Pritchard

For more about the Britten Sinfonia click here.