France Festival Arsmondo Argentina [2] – Ginastera, Beatrix Cenci: Soloists, Chorus of the Opéra national du Rhin, Orchestre Philharmonique de Strasbourg / Marko Letonja (conductor), Opéra de Strasbourg, 23.3.2019. (RP)

France Festival Arsmondo Argentina [2] – Ginastera, Beatrix Cenci: Soloists, Chorus of the Opéra national du Rhin, Orchestre Philharmonique de Strasbourg / Marko Letonja (conductor), Opéra de Strasbourg, 23.3.2019. (RP)

Production:

Director – Mariano Pensotti

Sets and Costumes – Mariana Tirantte

Lighting – Alejandro Le Roux

Chorus master – Alessandro Zuppardo

Cast:

Beatrix Cenci – Leticia de Altamirano

Lucrecia Cenci – Ezgi Kutlu

Bernardo Cenci – Josy Santos

Count Francesco Cenci – Gezim Myshketa

Orsino – Xavier Moreno

Giacomo Cenci – Igor Mostovoi

Andrea – Dionysos Idis

Marzio – Pierre Siegwalt

Olimpio – Thomas Coux

For centuries, the horrific tales surrounding the sixteenth-century nobleman Francesco Cenci have attracted poets, playwrights, painters, composers and film directors. His cruelty and lasciviousness knew no bounds. Roman society was appalled when he held a ball to celebrate the murders of two of his sons. Fixated with his daughter as a sexual being, he rapes her.

Power and wealth trumped such nasty little personality quirks, and expediency dictated that it was best left for a father to keep his family in tow. At least that is how the Pope viewed the matter. Cenci’s family, however, took matters into their own hands and arranged for his murder, with Beatrix disposing of the body. Their retainers broke under torture, and the family was sentenced to death. (Although not part of the opera’s plot, the youngest son, a mere boy, was forced to watch the executions and sent to sea as a galley slave.)

Intrigued by this horrific story, Alberto Ginastera worked with William Shand, a Scottish-born Argentine poet, novelist and playwright, to fashion a Spanish-language libretto based on Stendahl’s Chroniques italiennes and Shelley’s The Cenci. They pared the story down to a two-act opera in 14 scenes with the focus squarely on the father/daughter/wife dynamics. The rest of the male characters are secondary, except for Orsino, Beatrix’s former suitor and now a priest. Beatrix entrusts him with a letter to the Pope pleading for help, which he destroys, later lying to her that her entreaties have been rejected.

The opera had a starry premiere as part of the festivities surrounding the opening of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in 1971. Ginastera later remarked with a certain satisfaction that Leonard Bernstein had provided a Mass (a flop), while he had furnished the opera (a hit). It was not his first opera to be staged successfully in America, where the Argentinian composer had studied at Tanglewood with Aaron Copland in the mid-1940s and lived for a while in the late 1960s.

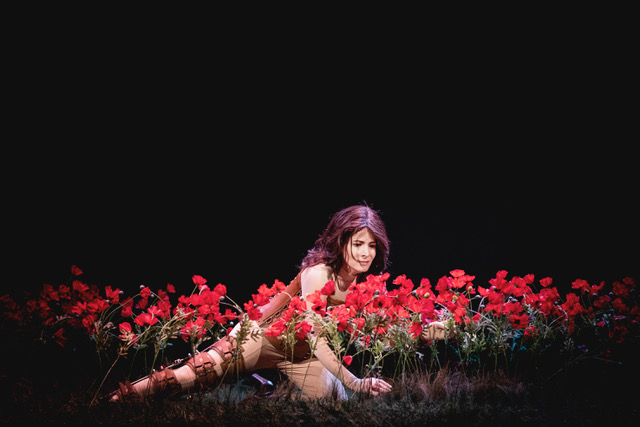

In keeping with the spirit of the 2019 Festival Arsmondo, Opéra national du Rhin engaged a creative team from Argentina, author and theater director Mariano Pensotti and choreographer Matias Tripodi, to create the new production. Pensotti updated the action to the present day, where instead of the grandeur of the Palazzo Cenci in Rome, the festivities, brutality and intrigues played out in rooms decorated in sleek, modern furnishings and gardens full of red poppies.

In their realization of the opera, Beatrix has one leg in a brace and walks with a pronounced limp. She appears to be naked, but is eerily androgynous in a flesh-colored body stocking. Her party dress is stylized leather armor with metal studs. Like Cenci and his wife, she later wears a luxurious fur coat. In the final scene, Beatrix is the equivalent of a piece of meat on a conveyor belt in a processing plant. Facing death, Beatrix’s greatest fear is that of seeing her father’s face in Hell for eternity.

The scenes played out on a revolving stage that created a dreamlike quality, as if one were sleepwalking through a horror story. Continuity was provided by the stage elements that reappeared in subsequent scenes: red poppies, statues of Beatrix and her armor. At the ball, Cenci unveiled a large statue of his naked daughter, shocking his guests. In the final scene, the workers pack white, smaller-scaled versions of it in boxes, while she is sealed a white, coffin-like one downstage.

Cenci’s dogs sent shivers down my spine: giant sculptures of Cane Corso or the Italian Mastiff, (the same breed as Ramsay’s ravenous hounds in Game of Thrones), their legs in brace-like studded metal boots. There are frequent references to the canines in the libretto, always accompanied by music that sounds like the jangling of metal on stone, which was much more terrifying than their recorded howls.

Ginastera’s score is awash with orchestral colors. The opera begins with a low growl in the orchestra, growing into complex textures that create an atmosphere of unrelenting fear and oppression. For the ball, he reimagined Baroque dances that disintegrated into jagged dissonance as the guests grasp the horror of the situation. The vocal lines are mostly angular, except for those of Orsino, for whom Ginastera composed soaring melodic lines worthy of Puccini.

Soprano Leticia de Altamirano’s Beatrix was a complex characterization of a woman victimized by an all-male hierarchy, who kills rather than crumble. In spite of the braces and armor, Beatrix’s femininity and vulnerability were always apparent. Likewise, there was a consistent lyrical quality to de Altamirano’s singing, her gleaming soprano cutting through and soaring above Ginastera’s dense orchestrations with sureness and ease.

As her father, baritone Gezim Myshketa was dissolute and deranged, and also somewhat of an art connoisseur. Fear gripped him as he was murdered, the stage dominated by oversized fragments of his daughter’s body suspended from above. No glimmer of humanity appeared in Myshketa’s voice, which sparkled with a menacing brilliance. His wife and Beatrix’s stepmother was Ezgi Kutlu, whose dark mezzo-soprano captured her character’s helplessness and revulsion at her husband’s actions.

It was difficult to warm to Xavier Moreno’s duplicitous Orsino, a self-serving worm of a man, but his tenor rang clear and true with real Italianate sound. Mezzo-soprano Josy Santos was lively and engaging as the youngest son, Bernardo. Fine appearances by baritone Igor Mostovoi as his older brother, Giacomo, and bass Dionysos Idis as Andreas, the family retainer, rounded out the cast.

In the pit, conductor Marko Letonja led a focused performance, maintaining the tension from beginning to end. The evolving scenes on stage and the pacing of the music were perfectly in sync, with the same attention paid to balance and music details. The Orchestre Philharmonique de Strasbourg and the chorus were excellent, displaying an obvious commitment to the drama and emotion of this challenging work.

In a production devoid of excess, Pensotti underscored the timelessness of the Cenci saga. No references were made to either #MeToo or the tales of sexual abuse that swirl about the Roman Catholic Church, but the connection was obvious. The impact of the final scene with Beatrix depicted as little more than a piece of meat was powerful. Operagoers are no strangers to violence and death, but this stark depiction of contemporary reality, where women and children are still subject to horrors similar to those which Beatrix Cenci experienced, left the audience sitting in stunned silence long after the curtain fell.

Rick Perdian