Germany Bayreuth Festival 2019 – Wagner, Tannhäuser [1]: Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of the Bayreuth Festival / Christian Thielemann (conductor). Festspielhaus, Bayreuth, 13.8.2019. (JPr)

Germany Bayreuth Festival 2019 – Wagner, Tannhäuser [1]: Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of the Bayreuth Festival / Christian Thielemann (conductor). Festspielhaus, Bayreuth, 13.8.2019. (JPr)

Production:

Director – Tobias Kratzer

Sets and Costumes – Rainer Sellmaier

Video – Manuel Braun

Lighting – Reinhard Traub

Dramaturgy – Konrad Kuhn

Chorus conductor – Eberhard Friedrich

Cast:

Landgraf Hermann – Stephen Milling

Tannhäuser – Stephen Gould

Wolfram von Eschenbach – Markus Eiche

Walther von der Vogelweide – Daniel Behle

Biterolf – Kay Stiefermann

Heinrich der Schreiber – Jorge Rodriguez-Norton

Reinmar von Zweter – Wilhelm Schwinghammer

Elisabeth – Lise Davidsen

Venus – Elena Zhidkova

Ein Junger Hirt – Katharina Konradi

The full title of the opera is Tannhäuser und der Sängerkrieg auf Wartburg but although we will see the contest between the Minnesingers the Wartburg Castle is sidelined in Tobias Kratzer’s new production. At the beginning of the overture we see drone video footage – from Manuel Braun – of the actual medieval castle amongst dense forest projected at the front of the stage. The camera pans down and focuses on a battered Citroën van driving along a road through the forest. This is where Tannhäuser now meets Pagliacci and inside it is a drum-playing dwarf Oskar (Manni Laudenbach) from Günter Grass’s The Tin Drum it seems; a flamboyant drag queen named Le Gateau Chocolat (UK born and raised in Nigeria); and, at the wheel, in a sparkly black unitard is a wide-eyed and rather neurotic looking Venus who appears to be the leader of this gang of misfits. They are touring the countryside living their alternative lifestyle and begging, borrowing, and stealing as they go. It is the latter that gets them into trouble as they are spotted siphoning petrol in an underground car park by a security guard who they run over and kill when rushing away from Burger King without paying for their food.

Wagner’s original story has the accomplished Minnesinger (a troubadour-knight), Tannhäuser, in the sensual realm of Venus, the goddess of love. He grows tired of all the delights on offer and returns to his fellow knights at the Wartburg Castle and to Elisabeth, a virtuous woman. Singing in the contest about the nature of love Tannhäuser is goaded to reveal the secret of his past life with Venus. The other knights are scandalised and ostracise him before sending him away with some passing pilgrims to see the Pope in Rome to seek absolution. It is initially refused, after which Tannhäuser returns to the Wartburg in despair and it is only after Elisabeth intercedes for him by sacrificing her life that his soul is redeemed.

In recent decades directors have struggled with the story, its clichés and medieval morality. Can it have any relevance for modern life? Sebastian Baumgarten’s recent 2011 Bayreuth production was not received well and although Kratzer also eschews Wagner’s original story he might have found more success. (Baumgarten’s Tannhäuser was set in a biogas plant and Kratzer references this at one point on a small sign at the side of the road that suggests it is now closed!) Now we see Venus distributing leaflets and pasting everywhere she can with posters with the words ‘Frei im Wollen, Frei im Thun, Frei im Geniessen’. This is quote from Wagner at a time in his life (around 1845) when he had sympathies with anarchism and it translates something like ‘free to desire, free to act, free to enjoy’. Venus disappoints Tannhäuser when she runs over the guard and he begins to have doubts about her way of life. The choice is between laissez-faire or conformism in art, as well as, love.

Most of this is seen on film and then the Citroën stops at a Snow White-like fairy-tale cottage. Here, Tannhäuser sings his love song to Venus whilst longing for his way out but Venus does her very best to dissuade him. He gets back in the van until it gets too much and he throws himself out of the door and onto the road. A passing cyclist — traditionally a shepherd boy — brings him round with an ode to Holda, a pagan goddess, before Tannhäuser praises God when he hears pilgrims on their way to Rome. For Kratzer ‘Rome’ is the Bayreuth Festival Theatre and the ‘pilgrims’ reflect an approaching audience like those sitting in their finery in the Festspielhaus now watching his Tannhäuser.

The theatre then becomes the stand-in for the Wartburg Castle; Langraf Hermann and the Minnesingers approach him wearing the lanyards you might see off duty singers and production staff wearing around the Grüner Hügel in the weeks of rehearsals prior to the annual festival. Tannhäuser, it turns out, is a cast member of his life as an opera and frequently refers to a score – probably of Tannhäuser – as a prop throughout Kratzer’s production.

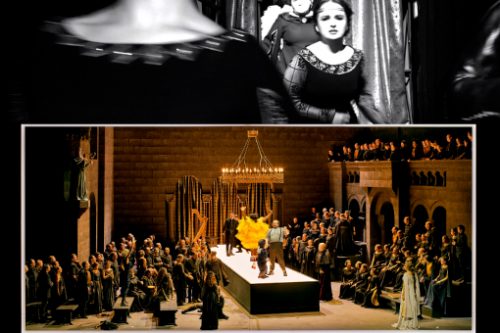

Act II shows a traditional-looking performance of Tannhäuser throughout the bottom half of the stage with backstage video projected above. At times this reminded me of the interval footage seen during live cinema broadcasts from the Metropolitan Opera and I expected Lise Davidsen – seen emerging from her dressing room – to be given a microphone for an interview! That does not happen, but we see her readying herself before she goes on to sing ‘Dich, teure Halle’. There is much more like that, as well as, showing the audience some of more humdrum moments backstage during a performance. Not only this but Venus, Oskar and Le Gateau Chocolat scale a ladder and invade the theatre creating mayhem and laughter. Indeed, Venus kidnaps one of the Edelknaben (noble pages) and takes her place during the song contest and reacts disdainfully to all the expressions of courtly love. Everything end when Katharina Wagner is seen in her office phoning for gun-toting police who are shown making their way to the Festspielhaus and at the end of act Tannhäuser is taken into custody. ‘Nach Rom!’ and redemption now means jail time because he will be convicted of the death Venus caused at Burger King.

Years have passed before Tannhäuser is released and he returns to find the gulf between the haves and have-nots wider than ever. He returns to a dystopian junkyard world and only Le Chateau Chocolat seems to have done well and – a large advert shows – has become the face of a high-end brand of watches. The ‘pilgrims’ are the poor and dispossessed (possibly recently released prisoners) who scavenge what they can. Oskar is living alone in what is left of the Citroën van; a distraught Elisabeth – who is in a self-destructive spiral – arrives and together they wait for Tannhäuser. Wolfram cannot control his desire for Elisabeth and indeed when he disguises himself in Tannhäuser’s clown costume he has sex with her: it seems consensual even though it is obvious Elisabeth knows it is Wolfram. When Tannhäuser does finally return it is too late as the shame over the depth to which she has sunk causes Elisabeth to take her own life. It all ends with Oskar, Wolfram and Tannhäuser – now wishing he had never met Venus (who is there with them) – united in their grief and all mourning Elisabeth. The final video we see is that of a happily smiling Tannhäuser and Elisabeth driving into the sunset for the happy ending they never will have.

There is a need to accept that in 2019 there is no place for a ‘traditional’ Tannhäuser and Tobias Kratzer’s Konzept was novel and thoroughly compelling. It was aided and abetted by the choice of the original sparer 1845 Dresden score adopted because – as suggested in the programme – it reflected better Wagner’s revolutionary zeal. It was given full value by Christian Thielemann and the always remarkable Bayreuth Festival Orchestra. Thielemann replaced Valery Gergiev who was mourning the death of his mother and. while there was much sympathy for the Russian maestro, the news that it would be Thielemann conducting was greeted rapturously by the audience. He offers extraordinary insights into the work bringing gravitas to the ceremonials of the Wartburg song contest that was worthy of the grail knights in Parsifal nearly four decades later. There was also much that was exhilarating elsewhere with a sensual flow to the music that seemed often at odds with what I understand about the Dresden score, as well as, Kratzer’s staging. It all sounded glorious, nonetheless. The contributions from the chorus as pilgrims was as outstanding as you would expect at Bayreuth and their sound was often overwhelming, occasionally too overwhelming I must admit, though their conductor Eberhard Friedrich continues to work miracles.

Most media attention had focussed on Lise Davidsen’s first appearance at Bayreuth. It is undoubtedly a wonderful sound, but she was a very stoic – slightly emotionless – Elisabeth and I did not feel enough connection between the notes she sang and a sense of her Elisabeth as a rounded character. Perhaps this is what Kratzer wanted? Nevertheless, there is no doubt her rise to further Wagnerian heights will continue. Stephen Gould on the other hand brought more nuance to his role and was the essence of a conflicted Tannhäuser who rebels against playing by the rules. His heroic sound – a touch stentorian at times – had unending reserves of stamina. Stephen Milling brought his typical cavernous tones to Landgraf Hermann. Markus Eiche was a fine Wolfram and again a finely wrought ‘O du mein holder Abendstern’ was totally at odds with his surroundings and – yet again – it did not matter much. Katharina Konradi was a superb Young Shepherd and all the Minnesingers were well-characterised and robustly sung. Elena Zhidkova threw herself with great abandon – body, soul, and voice – into the role of Venus and she deserved her own personal success, if only for her great comic timing.

Jim Pritchard

For more about the Bayreuth Festival click here.