Hymns and Suchlike

Or Emblaze Vulnerable Across Your Chest

It’s astonishing how tunes of the past well up unsolicited in moments of quiet, such as the bad old songs of yesteryear or rumbustious hymn tunes. They invariably bring a smile on the face if not outright laughter. My own repertory is sometimes evoked from the Music Hall – thanks to my grandpa who used to sing these numbers under his breath continuously. School assembly hymns of course. Whoever sang Guide me O thou great Jehovah to the rousing tune of Cwm Rhondda will never forget it. No one gave much for the words, but John Hughes’s tune is indelibly memorised.

The Salvation Army headquarters were around the corner from where I grew up; this was many decades before I recognised the magnificent charity work, they did with even an annual Christmas contribution. Or the outstanding training they (still now) continue to give to the country’s leading young brass players. But another Army episode, which had alarmed me at the time, continues to amuse me. I must have been about eight, so Cousin Sheila would have been about seven. We were playing on the street when a lady Army officer, complete with bonnet appeared. Hello Sally Army woman, said Sheila, do you love me? The woman looked as though she wished the earth would open up and swallow her. When she came round, she said, Go and ask Jesus. Sheila was furious. Stamping her foot, she said, I don’t want to ask bloody rotten Jesus; I’m asking you. Sally Army woman then scurried off, muttering to herself. I don’t know if the officer was court martialled for missed opportunity, but I burst out laughing, to be given a sharp kick on the shins from Sheila, who was in no mood for shenanigans. Theology and ecclesiastical procedure aside.

Why is it that the supposedly forgotten songs come to us in the shower? The other morning, I found myself singing what (on checking) turned out to be a windlass and capstan sea shanty/negro spiritual. It has to be sung lustily in pidgin English:

I nebber sin’ de like

Sin’ I bin born,

When di big buck nigger

Wi’ di sea boots on

Say Johnny come down to Hilo

Poor old man.

O wake her! O shake her!

O wake dat gal wi’di blue dress on,

When Johnny come down to Hilo.

Poor old man.

No political correctness of course. Hence the energising force of the mischief. English translations doubtless available for those in need. Still on negro spirituals, I have clear memory of Shirley Verrett following a lieder recital with a rich, velvety encore of Nobody knows de trouble I’ve seen. It crowned the Schubert and Strauss lieder in its passion and depth. Unequalled.

Across the years, thousands have celebrated their energies through this negro spiritual work song. Some songs never die. And this is one. Repetition is enforcing.

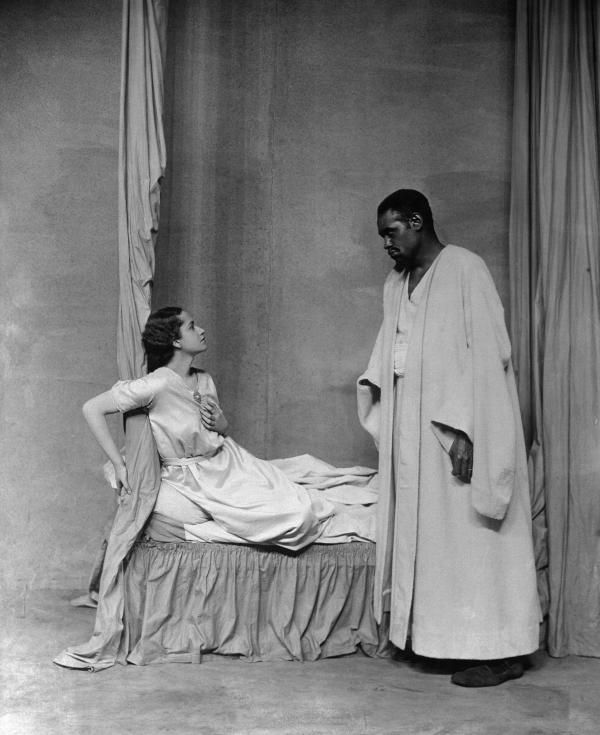

However, Paul Robeson (1898-1976) surely wears the crown for negro spiritual delivery. He was an African American, son of a slave and Quaker mother, nationally-lauded athlete, academic, political activist, lawyer and bass baritone. All those attributes are distinctly audible in his singing. He went straight to the hearts of Londoners when he appeared in the premiere of Show Boat in 1928, to be followed in 1930 at the Savoy Theatre (he couldn’t stay at the Savoy Hotel because he was black) in the title role of Othello. His Desdemona was Peggy Ashcroft – she was twenty-two. I’m killing two birds with one stone said Robeson, I’m acting and I’m talking for the negroes in the way only Shakespeare can.

Peggy would later say that looking back on it, it was inevitable what had happened to them on the Savoy stage. Robeson moved in with her, starting an affair which lasted over a year, much to the dismay of Essie, Paul’s wife. She filed for a divorce, which he refused, and later returned to her, though friends said that their marriage was never the same again.

You can hear the remastered recordings of Paul Robeson on YouTube. Ol’ Man River of course, but my own favourite is Shenandoah.

Sir Arthur Sullivan – the composer of the Gilbert and Sullivan collaboration – is another successful enforcer. You need only remember the tune of St Gertrude to the words of Onward Christian Soldiers to register his permanent fame, even of the hundred thousands who know that tune but not his name. That is real fame for you. More British identification than the Queen.

Yet Sullivan is arguably more entrenched in the nation’s memory – than for the onward-going Christian soldiers – with his beautifully moving tune of Samuel for these words:

Hushed was the evening hymn,

The temple-courts were dark,

The lamp was burning dim

Before the sacred ark;

When suddenly a voice divine

Rang through the silence of the shrine.

The suddenness of the divine voice could have been expressed from Sullivan’s genius alone. (Secret: this is one of the oldest tricks in the composer’s craft manual: a modulation to the dominant key which is instantly contradicted in the next bar. But Sullivan’s tricks never sound like tricks.)

His rendition of W S Gilbert’s words into music, try to persuade us that it is the words themselves that have composed their music:

When I was a lad I served a term

As office boy to an attorney’s firm.

I cleaned the windows and I swept the floor

And I polished up the handle of the big front door.

I polished up that handle so carefullee

That now I am the Ruler of the Queen’s Navee.

The security guard and queue manager at Croydon Waitrose supermarket is a huge, handsome, gentleman of Ghanaian ethnicity, called Prince (not making this up). When I asked James, the store manager, for the guard’s name, he asked me if it was the security officer who calls me, with a chortle, British man. That’s not how I try to present myself, but I enjoy this joke as much as Prince and James. I would have it emblazed across my chest if I thought it would make any difference. In fact, I discovered from James that it does make a difference, since it seems that because of my age I am considered vulnerable and along with NHS workers, the old crocks have access to restricted merchandise like toilet rolls, which James said he would bring me a huge package from the upstairs store (9 rolls) which will now service me for some time. This vulnerability also means that when Prince sees me in the queue outside, he can call me up to the front with anyone I happen to be with. I thought other people queueing might object to this. But they don’t.

Before I had discovered Prince’s capability, I had arrived at the queue, which had already turned a corner, at the same time as a youngish man, who recognising my age, insisted I had to go ahead of him. He turned out to be an Anglican church organist, who was locked out, since all churches were closed. He also worked as a jazz pianist in the evenings, but those venues had also been closed, so he was reduced to practising on his home piano. He was interested to know I was a musician. This led to my giving him a rendition of my shower song of that morning, Johnny come down to Hilo. That in turn, brought some laughter and applause from the queue. Have I found a new vocation? Maybe using the old Music Hall ploy of calling all together now for the second and subsequent choruses? I have long believed that anything that can be done to bring a smile on a face, or laughter from a heart, has done something useful.

Adelaide Proctor (1825 – 64) sold more copies of her poems than Dickens did of his novels. Quite an achievement. But she remains in memory today only for a few of these poems which found their way into the hymn books:

My God I thank Thee, who hast made

The earth so bright;

So full of splendour and of joy,

Beauty and light;

So many glorious things are here,

Noble and right.

It’s the third verse that pinpoints a theological subtlety in the same eloquent, irregular metre:

I thank Thee too, that all our Joy

Is touched with pain;

That shadows fall on brightest hours;

That thorns remain;

So that earth’s bliss may be our guide,

And not our chain.

The tune is usually Wentworth by Frederick Charles Maker (1844 – 1927)

The BBC continues to do a sterling job in entertaining us during the lockdown. They have just concluded a six-part dramatized documentary on the Corner Shop from Victorian times to the present and beyond. They remain on the indispensable BBC iPlayer, and while the episodes are uneven, they are a stimulus to the eye of any beholder. Watch this space for what I hope will be a measured, critical view.

Jack Buckley