Germany Wagner, Tannhäuser: Soloists, chorus and orchestra of the Bayreuth Festival. Conductor: Thomas Hengelbrock. Bayreuth Festspielhaus, 19.8.2011. (JPr)

Germany Wagner, Tannhäuser: Soloists, chorus and orchestra of the Bayreuth Festival. Conductor: Thomas Hengelbrock. Bayreuth Festspielhaus, 19.8.2011. (JPr)

I came back to Bayreuth for 2011 much later in the season than last year and it made reviews and the comments of colleagues from earlier performances difficult to ignore. As a result I sat down in the Festspielhaus for my operas this year with some preconceived ideas on how things were going to be, but on the whole things turned out much better than I expected. The perceived ‘scandal’ of this year’s Festival is Sebastian Baumgarten’s much-derided new Tannhäuser. I am grateful that these reviews reach a wide readership, and those who have read these musings before know I do not have a degree in art history, philosophy or music. My views on singing have been gained by experience and my comments on stagings are based on what Richard Jones, the thought-provoking British stage director, once told an audience member who asked what his Ring ‘meant’: ‘Well what does it mean to you?’

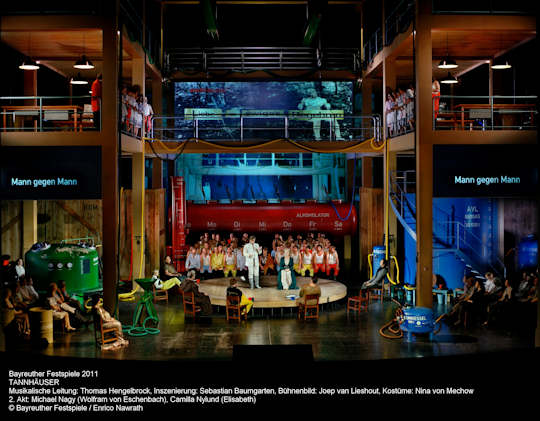

At Bayreuth we are faced with Dutch artist Joep van Lieshout’s self-named three-storey high ‘Techocrat Installation’ and he describes this as ‘an obsessive installation in which the human acts as operator and producer of excrements which are carefully processed in biogas. The biogas is then used for the production of food (no food – no excrements) and alcohol (‘we want happy people and no revolution’) . It is in this that German director, Sebastian Baumgarten’s, Konzept plays out: so throughout the entire opera we are in this biogas plant with ever-present tanks and pipework where the product itself is called ‘Wartburg’ and the aforementioned waste material (though thankfully little is actually seen) is recycled into the staples of life. The Venusberg rises from below ground and it seems that the recycling plant is a closeted ordered establishment where all the workers have their role; whilst the Venusberg is a Dionysian underworld where anything goes and it is peopled (is that is the correct term) by a subclass who are little more than rampant sexually-active beasts plus some excessively large (possibly Freud-inspired) tadpoles. The Mistress of Ceremonies for the bacchanal is a heavily pregnant Venus.

Videography is now a very common feature at Bayreuth and Christopher Kondek’s images are relentless right from the start when there is an X-Ray of a torso and the magnified microorganisms of the anaerobic digester (here my actual Biology degree came in useful). Frequently seen is a topless ‘Virgin Mary’ wiggling her toes and she is first seen against the backdrop of a human egg cell.

The set conceived here as this large ‘Art Installation’ could probably exist independently of the opera and indeed one of the novel features is that things are seen happening on stage as soon as the audience enters the auditorium and continue for some time when the music of each Act ends; van Lieshout explains how ‘the slaves of the Technocrat will continue acting during the pauses’. After Act II, for instance, benches are brought forward and the workers participate in a liturgical church service. Before Act II there was a video of the cast doing a rehearsal read-through of the libretto; at the beginning of Act II the words ‘Wir sind krank’ (We are sick) were displayed and the whole opera ended with Wagner’s own words that he still owed the world a Tannhäuser. There are also two sets of seated onlookers on either side of the front of the stage – it is not clear who they are, perhaps just the audience at a performance art event.

Again typical of new productions at Bayreuth in the twenty-first century is that the Act I ‘scene-setting’ is just too busy and did not work for me; my attention was drawn here and there across the stage without any great result. Act II, setting apart, was a reasonably clear exposition of the Tannhäuser story despite the presence of Venus at the song contest who becomes the object of an increasingly drunk Tannhäuser’s desires. Earlier Elisabeth’s opening ‘Dich, teure Halle’ became something of a ‘Jewel Song’ as she is shown putting on rings, ear rings, bracelets and necklaces readying herself for the return of the man she has given her heart to. The last twenty minutes of Act II had a powerful impact, more than anything preceding it. In defending Tannhäuser from the wrath of the knights, Elisabeth seems on the edge of madness with something of a martyr complex as she uses a dagger to create stigmata in her hands – and when there is insufficient blood she seems to improve this with some red paint that is lying around. She orchestrates the crowd into giving Tannhäuser one last chance by literally packing him off to Rome in a large crate with the other pilgrims. At this point the ensemble singing from soloists and chorus was everything you expect from Bayreuth though individually much of the casting was below par.

Act III was the best of the three: it was clear Venus is pregnant but Elisabeth might also be and there is the fertilisation of an egg shown during the opening music. Elisabeth shuns Wolfram and is so distraught when Tannhäuser is not with the returning pilgrims – shown here as cleaners with OCD – that she recycles herself by entering the large biogas digester and Wolfram forces the door shut behind her. This was a very apposite image for me as I had been thinking during the interval about the classic Sci-Fi film Soylent Green where humans are processed into food for a starving population. Elisabeth’s prayer ‘Allmächt’ge Jungfrau, hör mein Flehen!’ was deeply moving, as too was Wolfram’s ‘O Du, Mein Holder Abendstern’ and these were Camilla Nylund and Michael Nagy’s finest moments. The Pope’s staff returns having gone ‘green’ and this outcome was undoubtedly part of the inspiration for this eco-friendly production. Elisabeth is reborn through Venus, of all people, and both Venusberg (mutant tadpoles and all) and the Wartburg seem redeemed.

As Tannhäuser, Lars Cleveman, rose to the challenge of his demanding Act III Rome Narration though his voice is just a touch too small for the Festspielhaus and his timbre is that of a character tenor. Nevertheless he displayed Tannhäuser’s anguish and anger at the Pope’s failure to absolve him of his sins with great dramatic skill and by marshalling his resources he suggested – that in the right-sized opera house – he could be a potent Tristan.

Overall as suggested earlier most of the cast was, at best, solid but not memorable and the fury of the unforgiving Bayreuth audience was unleashed on Stephanie Friede’s hard-on-the-ear, squally, Venus. Lars Cleveman was also booed and this was a little harsh in my opinion as I believe by making Tannhäuser unromantic, dishevelled and unappealing, he was only doing what Sebastian Baumgarten asked of him. He did not come out in front of the curtain at the end of the opera but I hope he will come back to Bayreuth. Günther Groissböck was a quite youthful Landgrave without perhaps the bass notes and some of the gravitas the role requires.

Thomas Hengelbrock’s reading grew in stature during the evening. Perhaps mimicking the cold and clinical staging it lacked a sexual frisson for much of Act I but much more ceremonial spaciousness and emotional intensity came through in the other Acts. The orchestra played faultlessly and the chorus were their usual incredible selves.

Bayreuth’s caterers apparently scuppered the plans of the director and designer to perform the opera without an interval and Maestro Hengelbrock also wanted to conduct his own version of the score but could not. This might have made the impact of what we were seeing greater had this been allowed to happen but it was a Tannhäuser that was not as bad as I was led to believe. If it is allowed to develop in Werkstatt Bayreuth in forthcoming years – unlike the Schlingensief Parsifal with which it shares many features – it could gain significantly in popularity rather than notoriety.

Jim Pritchard