Germany R. Wagner, Das Rheingold: Soloists, Kent Nagano (conductor), Bavarian State Orchestra, National Theater, Munich, 9.2.2012. (JFL)

Germany R. Wagner, Das Rheingold: Soloists, Kent Nagano (conductor), Bavarian State Orchestra, National Theater, Munich, 9.2.2012. (JFL)

Direction: Andreas Kriegenburg

Sets: Harald B.Thor

Costumes: Andrea Schraad

Lighting: Stefan Bolliger

Choreography: Zenta Haerter

Dramaturgy: Marion Tiedtke, Miron Hakenbeck

Cast

Wotan: Johan Reuter

Donner: Levente Molnár

Froh: Thomas Blondelle

Loge: Stefan Margita

Alberich: Wolfgang Koch

Mime: Ulrich Reß

Fasolt: Thorsten Grümbel

Fafner: Phillip Ens

Fricka: Sophie Koch

Freia: Aga Mikolaj

In Wagner a pronouncedly conservative set of expectations meets—and often clashes with—pronounced experimentation on stage. That tension is very befitting a Wagner opera, given the mix of (mildly) reactionary elements in the composer’s later stages and the radically innovatory, (literally and metaphorically) revolutionary stance of his work and political youth.

That Andreas Kriegenburg, in charge of the Bavarian State Opera’s 2012 Ring, managed to cleave, rather than exacerbate this potential rift, is a credit to his imaginative, nuanced, and sensitive production. Kriegenburg, a theater director relatively new to opera, has a penchant for visually arresting productions; a spectacular Prozeß (Franz Kafka, Munich Kammerspiele) and one of the best performances in 2008, a spellbinding Wozzeck (Berg, Bavarian State Opera – review here) are only two examples. The Munich Rheingold is not spectacular in the same way; it succeeds in a slower, more subtle way. Instead of being outright awed during the two and a half hours, I found myself quietly admiring Kriegenburg’s solutions and ideas.

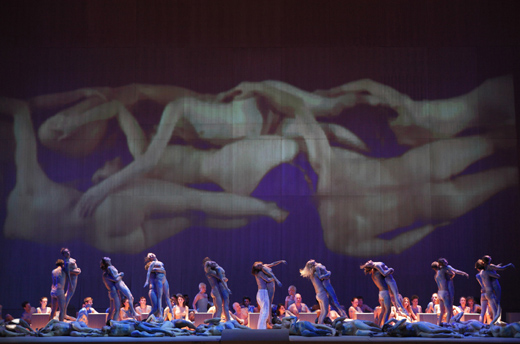

Bodies are the main ingredient in Kriegenburg’s visual quiver. He uses them to depict the elements, the Rhin, the forces of earth when Erda appears, and the battlements of Valhalla. Compressed (using dummies) into two cruel cubes, Kriegenburg provides Fasolt and Fafner with bodies to stand on; stand-ins for the human cost of ambitious building projects: Two times 120-some cubic feet of crushed humanity, somewhere between Damian Hurst and Gustav Vigeland.

Even before the opera starts, the large stage is filled with a hundred extras—men and women clad in white, with the three mint-green Rhinemaidens in their midst. Gurgling sound of water comes from the speakers, the light dims, and the corps of swimmers strips down to flesh colored undies and they begin to paint themselves blue; more Braveheart-style than Smurf-ish. With Kent Nagano’s downbeat to those famous 136 bars of E-flat major, the boating party morphs into a physical representation of the Rhine, one intertwined couple at a time. The Rhinemaidens navigate securely through this body of water, playing with the waves. When Alberich lustily makes his way toward the ladies, the animated stream—in perfect tune with the music—throws him about. When the Rheingold comes into view, it is a petite gold-plated dancer, first ‘carried in’ by the waves and then very literally abducted by the taunted dwarf. A few scenes employing large numbers of extras falls flatter than presumably intended: The Niebelungs have to cheaply fake the stacking of the pre-stacked gold. And when Donner summons the clouds (Zu mir, du Gedüft! / Ihr Dünste zu mir! / Donner der Herr / ruft euch zu Heer!), the white-clad masses wave flexible silver and gold plated cardboards about, presumably to dispel the heavy fog… except that they don’t affect very much at all and end up looking rather dispensable.

Platinum blondes all, the Gods are dressed in black or muted colors, except for Loge (equally blonde where expected piebaldism to hint at his being half of light like the gods and half of darkness) who stalked the stage in flaming red and comes across like a mix of Julian Assange, Bond Villain and Heinz Zednik’s supreme Loge in the Chéreau production, though never as toadying as the latter was made out to be. Trying to retrieve his cane from Fricka’s grasp, the dagger that slips out of the shaft reveals his discrete sword cane’s secret. Loge, an accelerant by nature, later dangles that dagger alluringly before Fafner who grabs at the opportunity and does away with Fafner to the fierce, fearsome stabs of the orchestra. Another visual nod to Chéreau are the enormous puppet-hands on the giants’ oversized suits, worn only when they are immobile on their human cubes; with extras in colored sacks posing as legs and shoes.

For the Nebelheim scene the stage rakes steeply from the bottom; met similarly from above, with just enough space between them to see the slaving Niebelungs through a wide, chink of burnt orange. Broken down Niebelungs are tossed over the ledge and disposed in hatches that emit, per victim, a burp of flame and smoke… the collateral of gold-digging. When Alberich is asked to show off the powers of the Tarnhelm, the transformation is ‘hidden’ by the fellow mining-henchman who turn the lights with which they illuminated the darkness to the audience, blinding four thousand eyes long enough for Alberich to scram and a flaming snake on sticks—above the battery of lights, (imperfectly) hiding those who carry it—to wind its way about stage. The toad, in turn, is another lithe little dancer in a green costume, easily carried away by Wotan & Co.

Neither outstanding production values nor the sensitive direction would have made this such a promising beginning to the Ring-journey if the musical aspect hadn’t also been marvelous. In an unassuming way, not unlike Kriegenburg, Nagano led an impeccable band (two brass-blunders aside) in a seamless, gorgeous reading and a cast that was extraordinarily even and homogenous. Starting with Johan Reuter’s Wotan, who was the vocal equivalent to Nagano’s orchestral sound: A most lyrical Wotan, not a massive voice but a confident one that sounded like it never needs to be bigger than it was to convey its authority. He was flanked by Sophie Koch’s Fricka, who started with that hint of irritation in her voice, but added enough frailty, warmth, and beauty so as not to fall victim to the harridan cliché. Froh and Donner—Thomas Blondelle and Levante Molnár—impressed with the ever-audible pleasant lightness and clarity that made the Rhinemaiden-trio (Eri Nakamura, Angela Brower, Okka von der Damerau) a subtle delight. Neither mellifluous Fasolt (Thorsten Grümbel) nor hardened Fafner (Phillip Ens) exceeded reasonable expectations, without falling short of them, either. Stefan Margita (a wonderful Laca in Munich’s Jenůfa) was the liltingly-accented Loge, with a concentrated, beautiful, and clear voice, evocative of Klaus Florian Vogt’s, including the slight nasal quality but with a stronger tone. Wolfgang Koch, recovered after missing the premiere, makes for a regal Alberich and Ulrich Reß’ very agreeable Mime comes without squeaky silliness. Aga Mikolaj’s Freia was the lone lush voice among the Gods, which served to underscore her sensuality.

One musical quibble I was left with was that Fasolt’s ‘Shylock moment’ (“ein Weib zu gewinnen / das wonnig und mild / bei uns Armen wohne…”), the only expression of true, unspoilt, selfless love in the entire Ring, was brushed over a little. Wagner gives some of his most beautiful music—however briefly—to the lovelorn giant and would have deserved highlighting. But then that would not match the perfectly descreet, coolly Italianate conducting of Nagano. (The direction picked up on it, though: Freia shows more than a certain responsiveness to Fasolt’s emotions—much to the dismay of her jealous brethren Donner and Froh—and she’s the only one devastated at his death.) But to end on a quibble would do this production injustice because I left the opera house myself with a very rare sort of cheerful, happy delight of having had an unreservedly wonderful time at the opera house.

Jens F. Laurson