United Kingdom Glass, The Perfect American (UK Premiere) : Soloists, Chorus & Orchestra of English National Opera/Gareth Jones. London Coliseum, London, 01.06.2013 (CC)

United Kingdom Glass, The Perfect American (UK Premiere) : Soloists, Chorus & Orchestra of English National Opera/Gareth Jones. London Coliseum, London, 01.06.2013 (CC)

Cast

Walt Disney: Christopher Purves

Roy Disney: David Soar

William Dantine: Donald Kaasch

Hazel George (Disney’s nurse): Janis Kelly

Lilian Disney: Pamela Helen Stephen

Sharon: Sarah Tynan

Diane: Nazan Fikret

Lucy/Josh: Rosie Lomas

Abraham Lincolm/Undertaker: Zachary James

Andy Warhol: John Easterlin

Chuck/Doctor: David Campbell

Secretary: Amy Kerenza Sedgwick

Nurse: Claire Pendleton

Production

Director: Phelim McDermot

Choreographer: Ben Wright

Designer: Dan Potra

Video designer: Leo Warner (59 Productions)

Animation designer: Joseph Pearce (59 Productions)

Philip Glass is astonishingly fertile of invention when it comes to opera. The ENO Press Pack claims this is his 24th opera, although I suspect that might mean the broader “works for the stage”. Nevertheless, it is an impressive achievement. Works such as Akhnaten and, especially, Einstein on the Beach, have attained a near-iconic status. Plus, he sells out opera houses; not a spare seat was to be seen on this occasion.

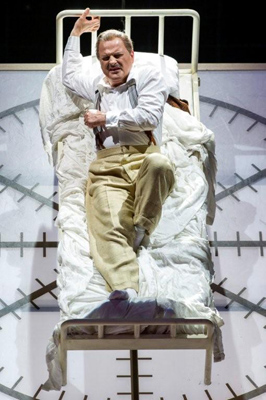

This is a rare example of an opera providing a finer piece of art than the work it is based upon. In this case, the “work” is Peter Stephan Jungk’s novel The Perfect American, a book that, whilst engaging, is only a little bit above the offerings that one might find, say, in the reduced price daily email from Amazon’s Kindle Store. Glass’ take on the subject matter, a fictionalised version of the life of Walt Disney, seen in a stream of Ruckblicken from his hospital bed in St Joseph’s Hospital, California as he deals with terminal illness, takes us way further than Jungk ever does in his book.

This way of working – looking back from a static space wherein drama also happens – poses huge challenges for a staging. ENO here works in collaboration with Improbable Company to create a visual spectacular. The staging is full of the sort of thing that ENO excels at, to the extent they are trademarks: cinematic projections, expert lighting and seemingly technically insurmountable scene changes. Improbable Theatre Company has as its Artistic Director and co-founder the British director Phelim McDermott, whose production is such a feast for the eyes (McDermott made his ENO debt back in 2005 with more Glass: Satyagraha). 59 Productions is the company responsible for the video design and animatronics. A few first night glitches apart, things went mostly to schedule. None of the Disney characters are seen, though, because of copyright reasons. People seem to hop around like rabbits a lot though (Bugs, I assume), and a large circle with two smaller circles (ears?) on top does seem to point somewhere in the direction of Mickey Mouse …

As to the central character, this is not the cutesy Walt Disney that every child holds in their head. This is a tale of moral corruption, of a man with a passion to control, a man who couldn’t actually draw the creatures he is so identified with; there is a small army of cartoonists onstage who work, just like factory workers, to churn out the images for the awaiting public. It is also a tale of Disney’s purported idea to be cryogenically preserved – a rumour that attended his death back in 1966. The flashbacks repeatedly go back to his hometown of Marceline, Missouri. There is also a “stalker”, William Dantine (although he is portrayed as a more important character in the book than in the opera). He is listed in the cast list as “a former Disney employee” – more accurately, a much disgruntled employee who was sacked without mercy and who has been making various approaches to Disney ever since, or just plain spying on him.

In dealing with Disney, Glass shifts from the Gods of religion (Akhnaten) and science (Einstein, Kepler) to the latter day hero-god – or icon, if you prefer, something which seems to be confirmed by the appearance of Abraham Lincoln (more accurately, an animatronic machine that delivers Lincoln’s most famous speeches) and Andy Warhol. The immediate reference point there, one assumes, would be Michael Dougherty. But as a composer Glass is in a different league.

As Disney, Christopher Purves is outstanding. He is a fine singer – the evening I saw him at the Royal Opera House in Benjamin’s Written on Skin, he was on top form (I believe my colleague Mark Berry, who reported for Seen & Heard, was present on a different night). Purves shone here, too. His stage presence is perfect for the egotistical Disney; his voice, too, is huge enough to project Glass’ lines to the farthest reaches of the Coliseum. Which brings me to lines – or melodies, or even tunes, if you will. There is something of a sea-change in this, Glass’ almost-newest opera (there is one even more recent one). The score is shot through with lyricism. The objectivising repetitions of hard-core minimalism have been (largely) replaced by something softer, something more immediately malleable, something more responsive to a moving situation. The music is often beautiful, as if we are being led to be sympathetic to this rethought Disney.

Zachary James was an amazing Abraham Lincoln. Having a person play a fairground machine that is supposed to deliver a Lincoln speech (the Gettysburg address, I believe) but which malfunctions hilariously is a wonderful idea, and James brought all of the gawkiness of a shortcurcuit to his portrayal.

Donald Kaasch brought much to the reduced-calorie role of William Dantine, acting out the role of a rather pathetic tramp-like figure to perfection. As Roy Disney, the brother, David Soar was completely convincing as the hard-nosed business man-cum-protector, while Janis Kelly (Hazel George, Disney’s nurse) and Pamela Helen Stephen (Lillian Disney, his wife) added colour and character. But it is perhaps the young singer who played both the child Josh and Lucy that stole the show, Rosie Lomas, who graduated from the GSMD as recently as 2011. Josh is the boy who meets Disney in hospital, initially does not know who he is and then finds out his hero is there with him. It makes for touching opera, to be sure. To play to a full house in such a high profile event so early in one’s career must be daunting in extremis, and this was a most impressive showing.

A last-minute cast change, announced in front of the curtain immediately prior to the opera’s onset, was brought about by the indisposition of Christopher Speight, who was to have taken the roles of Chuck/Doctor. David Campbell, a bass of the ENO Chorus, was brought in at the eleventh hour. Perhaps Campbell was not the most confident of the singer/actors on stage, but the show must go on …

And so it will, doubtless, for the remaining eight performances. It is a pleasure as well as a pleasurable surprise to give a wholehearted recommendation to this opera, and good to see the man himself take a bow (Glass, not Disney, that is). Glass, I am sure, has more surprises yet.

Colin Clarke