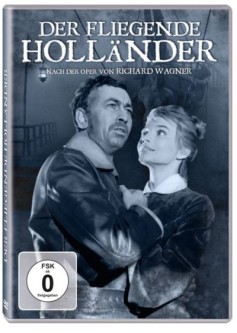

United Kingdom Wagner, The Flying Dutchman (Director Joachim Herz’s 1964 B&W film Der fliegende Holländer), Soloists, Leipzig Opera Choir, Leipzig Gewandhausorchester / Rolf Leuter (conductor), Screened in association with Wagner 200 at the Barbican Cinema, London, 7.12.2013. (JPr)

United Kingdom Wagner, The Flying Dutchman (Director Joachim Herz’s 1964 B&W film Der fliegende Holländer), Soloists, Leipzig Opera Choir, Leipzig Gewandhausorchester / Rolf Leuter (conductor), Screened in association with Wagner 200 at the Barbican Cinema, London, 7.12.2013. (JPr)

Cast:

Anna Prucnal (Senta) sung by Gerda Hannemann

Fred Düren (Dutchman) sung by Rainer Lüdeke

Gerd Ehlers (Daland) sung by Hans Krämer

Mathilde Danegger (Mary) sung by Katrin Wolzl

Herbert Graedtke (Erik) sung by Rolf Apreck

Hans-Peter Reinecke (Steersman) sung by Karl-Friedrich Hölzke

Production:

Director – Joachim Herz

Screenplay – Joachim Herz & Harald Horn

Assistant Director – Eleonore Dressel

Cinematography – Erich Gusko

Art Direction – Harald Horn

Costumes – Gerhard Kaddatz

Sound – Günter Lambert

Choreography – Ruth Berghaus

Chorus Master – Andreas Pieske

Being screened throughout the world in 2013 as part of the 200th anniversary of Richard Wagner’s birth is the newly-restored version of one of the first complete (or nearly complete – in this case) Wagner operas on film. Joachim Herz’s successful staging of Der fliegende Holländer at Berlin’s Komische Oper in 1962, at the invitation of Walter Felsenstein, and subsequent productions in Leipzig and Moscow, prompted an invitation to make a cinematic adaptation.

We all know the legend of course: the Dutchman is actually unable to die having been condemned to sail endlessly around the world’s oceans and can only be redeemed by a woman’s eternal love. Senta is the daughter of a rich ship-owner, who in order to escape her narrow and restrictive life seeks refuge in her dream world and fantasies. In this realm of her imagination, a bold and restless sea captain appears to her – the Flying Dutchman – and Senta frees this man through her love for him.

Patrick Carnegy’s informative film notes revealed, ‘Herz’s “Film nach Wagner” fairly painlessly shortened the composer’s score … His aim was to make a real film (i.e. not to film a stage performance but to make a film based on Wagner’s text and music) that would open up opera “to people who have a horror of it” ’. About the ‘soundtrack’ Carnegy added that ‘Four weeks were spent pre-recording the music … each singer’s voice being recorded on a separate track. The use of four-track stereo sound (for the first time in European film making, claims Herz) enabled the “voices” to issue from the separate cast of miming actors whenever they happened to be in screen-space. The Dutchman’s ghostly crew is intended to be heard as though from the rear of the cinema.’

Made for DEFA (the state controlled film company), this film is unique as it the only East German one ever made that includes elements of the horror and vampire genres and also it is one of the few films in the world to be shot in a combination of 4:3 aspect ratio and Cinemascope; the former is used for the prison of Senta’s genuine existence and the visual image broadens out when she is indulging in her fantasies.

Herz’s widow, Dr Kristel Pappel-Herz, came from Estonia and was present at the screening to introduce it: she explained how his original Konzept that Senta dreams about the Dutchman (something that has become very popular in stagings of Der fliegende Holländer over the last 50 years) meant ‘some rearrangement of the scenes at the beginning of the film’. We heard how Herz was influenced by Romantic Art, such as the works of Caspar David Friedrich, and 1920s’ German Expressionist cinema, as well as, the films of Ingmar Bergman. Why were actors used? Well it was because it would have been difficult to hire opera singers for such a long recording period – and not every opera singer is suitable to be shown in close-up on the big screen. (The Metropolitan Opera and Royal Opera live cinema broadcasts show that to be only too true!) Intriguingly we were told how the Dutchman, a distinguished Berlin actor called Fred Duren, is now a Rabbi in Israel; also, how the film is a visualisation of Herz’s ideas of Musiktheater, where the action we see is based on the music we hear. Poignantly speaking some of her husband’s own words she revealed how the end is unresolved as we do not know what becomes of Senta although she is shown holding a picture of the Dutchman and has apparently arrived ‘at a land called “Utopia” ’.

Through careful restoration Joachim Herz’s realisation of The Flying Dutchman is a visual treat and is set firmly in the Biedermeier period of Germany’s cultural history c. the 1840s – the time of the opera’s composition – with Czech mountains and Berlin lakes forming the backdrop to the familiar tale. One does not need to be an expert on German Expressionism to appreciate the use of extreme close-ups, swirling mists, low or skewed camera angles, shadows or backlighting, because all this crossed over to Hollywood in the early twentieth century and is redolent of the work of James Whale or Tod Browning in the classic horror (as well as, other) films of the time. Intriguingly Herz shows the Dutchman somewhat diminished in scale against the overall impact of his storm-ravaged phantom ship; he is not in any way a romantic hero and seems to have had more than enough of his sea-voyage-without-end. Fred Düren’s Dutchman certainly appears at Senta’s door with the pale, haunted look of a vampire who hasn’t had a good ‘meal’ for ages. Was it just me or did the figurehead of his ship bear more than just a passing resemblance to the Statue of Liberty? Given the state of political relations between America and the Communist Eastern bloc during the 1960s I would be surprised if this was just a coincidence.

Seen through twenty-first sensibilities Anna Prucnal wide-eyed Senta looked to be very frightened of Daland, her father, and with her locked door it very much hinted at the start that she might be suffering some form of abuse and this was the cause of her retreat into a happier fantasy life given every opportunity. The spinning girls are suitably scornful during her ballad; Erik, the huntsman, is his usual ardent self and the rampaging Dutchman’s zombie-like crew are more horrific than is ever possible on stage. To those familiar with the state of modern Wagner singing the voices we hear coming from the mouths of the actors much lighter than we are now used to but this was apparently deliberate as it was ‘part of Joachim Herz’s turning his back’ against the artifice of opera so ‘music and action would seem causally intertwined’.

As the always perceptive Patrick Carnegy concludes: ‘The film ‘remains extraordinarily close both to the way Wagner composed and to his ideas about how his works should be performed.’ If you have never seen this intriguing version of The Flying Dutchman, do so if there is the opportunity, or add the DVD to your collection.

Jim Pritchard

This 2013 re-release is available on DVD at very little cost through http://www.amazon.de and other suppliers.