United Kingdom Haubrich, Morrow, Beethoven, 6000 miles away: Sylvie Guillem and Friends, Birmingham Hippodrome, 6.5.2014 (GR).

United Kingdom Haubrich, Morrow, Beethoven, 6000 miles away: Sylvie Guillem and Friends, Birmingham Hippodrome, 6.5.2014 (GR).

27’ 52

Choreography & Design: Jiří Kylián;

Music: Dirk Haubrich (based upon Mahler themes);

Dancers: Aurélie Cayla & Lukas Timulak.

Rearray

Choreography & Design: William Forsythe;

Music: David Morrow;

Sylvie Guillem & Massimo Murru.

Bye

Choreography & Design: Mats Ek;

Beethoven (Piano Sonata Op 111, 2nd movement);

Dancer: Sylvie Guillem.

Once in a while an artist comes along who seems to defy the ravages of time. Conductors seem to manage remarkably well and like soldiers never seem to die: Arturo Toscanini retired at eighty-seven years young. Dancers often expose their bodies to what seem to be excruciating levels of torture that often bring their careers to a premature end. It varies, Darcy Bussell retired at a mere thirty-eight while Margot Fonteyn made it to sixty-one. Sylvie Guillem is now forty-nine and can still hoof it with the best of them as she manifestly demonstrated on May 6th 2014 at the Birmingham Hippodrome, one of the highlights of this year’s International Dance Festival Birmingham. Now in full swing IDFB 2014 continues until May 25th.

6,000 Miles Away, Guillem’s triple bill first staged in 2011, was conceived as a mark of respect to the distress the natural disasters had upon Japan in that year. But it means more that that, crystallising her belief that works of art can bridge both continents and cultures. Her programme of contemporary dance to compliment the music of one classical composer and two distinctly 21st century exponents, succeeded in providing an irresistible combination together with universal appeal. Premièred in 2002, Jiří Kylián’s 27’52”opened the proceedings; it owes its title to the length of the piece, although here it was slightly shorter. The female lead was Aurélie Cayla, and partnered by Lukas Timulak they renewed their roles from last year. Both began by seemingly doing their own thing: Cayla, in a red top and dark slacks, jerking along to the clockwork sounds of Dirk Haubrich, while Timulak emerged into view from beneath a stage mat; how were they to come together? As they cavorted around it struck me that this was a boy-chasing-girl situation with the girl initially being repulsed by the boy’s advances since each time he caught up with her she scarily jumped away. However a few lifts and sorties later Cayla discarded her top, identifying herself with her already bare-chested partner. But reduced to a motionless lump on the floor, perhaps she was beginning to have regrets regarding her impulsive actions. And the snatches of spoken lines, both male and female, presumably to represent each of the protagonists (droned mainly in French I thought) threw little light on the narrative, if there was one! Likewise the subtle lighting of Kees Tjebbes added to the mystery. To the high-pitched electronic monotones of Haubrich (about as far from Mahler as you might imagine) the couple appeared to gradually engage with one another. Along with some further weird noises that reminded me of a grasshopper, an analogy that seemed appropriate as the pair rubbed their legs together. If the course of true love did not appear to run smooth between them, there was nevertheless a extreme silkiness and grace to their basic movements, and there was their beautiful bodies to admire. The final chase produced its own twist: Timulak appeared to have enwrapped Cayla in his arms and a second mat; however she ran off and sought refuge under the mat from which Timulak had originally emerged. Why didn’t he follow? Only Kylián knows!

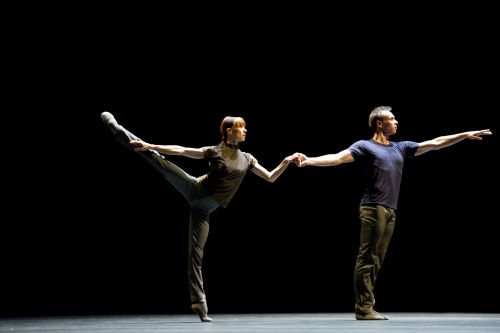

Rearray was Guillem’s fourth collaboration with William Forsythe and second on this Festival bill. It was like many ideas for new ballets a direct transformation from the drawing board of the rehearsal room. The exercises that form the core syllabus of all ballet schools are painted into a musical frame, enabling the dancer to show off their technique, something that has never been an issue with Guillem. Here she was partnered by another master technician, Massimo Murru (see picture) a favourite of Roland Petit who chose him as Don José in their dynamic version of Carmen. Those familiar with the work of Paris Opera teacher Gilbert Mayer would have luxuriated in the succession of low jumps and beaten steps. Notable among the many delightful sequences was the intertwining of the dueting pair: Guillem seemed to make her legs her arms, her lower limbs floating as gracefully as any gull on a seaside promenade, upper ones as rigid as a pit prop; meanwhile Murru reversed the process, making his arms as sturdy as an oak, a safe haven for Guillem to fall into. A magical interlocking procedure! This sequence was just one of the ideas to come out of the preliminary conversations between Guillem and Forsythe. Spotted by Nureyev at nineteen while at Paris Opera’s Ballet School, Guillem demonstrated that she has retained her pliancy some thirty years later, now an honorary OBE for services to The Royal Ballet. Of modest height, her plumb-line six o’clock position en pointe made it look as if her legs went on forever – and you could easily have calibrated a setsquare on her quarter-to. Yet again though I thought the minimalistic music of American David Morrow failed to structure the whole, its presentation exacerbated by the up/down, on/off lighting of Rachel Shipp. But the dancers conquered these shortcomings in style!

The third item satisfied my principle ballet objective – for the movement to gel with the music. Again Guillem was reunited with a choreographer with whom she has enjoyed a treasured working relationship – the Swede Mats Ek. His Byeemploys music from a different genre, late Beethoven. A master composer of the Piano Sonata, his Op 111 in C minor was his final word on the piano sonata; having expressed all he thought he could from the piano, he said goodbye to it with its second movement, Arietta, Adagio molto, semplice e cantabile. Ek thus had a theme on which to elaborate and he created an exquisite vehicle for Guillem; it was a natural for her and as Ek says, she knows how to dance. The choreographer used the musical variations that organically grow within the passage to full advantage. The piece began with a celestial calm (a sensation not witnessed throughout the previous two offerings), a serenity that grew in complexity as the recorded rendition of pianist Ivo Pogorelich unfolded. I thought Guillem’s timing was meticulous: imitational knocks to the staccato notes; swivelling about her trunk to the rolling rhythms; fluidic leg vibrations to simulate the semi-quaver trills; head-stands that engaged with the balance of the whole movement. All and more were on the button. Typical of how Guillem effectuated a mood was the way she hung her arms to give a sombre, heavy body appearance from a frame that was anything but. All achieved whilst wearing a simple yellow skirt and purply top, as if she was a mere mortal like us. Not a chance!

The evening did much to underline the durability of Guillem who refuses to allow time to interrupt her desire to entertain the public. Old Father Time, synonymous with Lords, the home of the English game of cricket that can be traced back to the early 16th century, has a sculpture that depicts the removal of the bails from a wicket to signal the end of the game; for Guillem and dance, play has not ended, it’s not yet time to remove the bails.

Geoff Read