United Kingdom Johann Strauss: Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of Opera Warwick / Paul McGrath (conductor), University of Warwick Arts Centre, Coventry, UK, 19.1.2017. (RD)

United Kingdom Johann Strauss: Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of Opera Warwick / Paul McGrath (conductor), University of Warwick Arts Centre, Coventry, UK, 19.1.2017. (RD)

Johann Strauss – Die Fledermaus, in a new translation by Josh Dixon (with Eve Miller)

Cast:

Eisenstein – Ross Kelly

Falke – Cole McLaren-Bailey

Rosalinda – Ellie Popham

Adele – Natasha Agarwal

Ida – Charlotte Senior

Prince Orlofsky – Ellie Sterland

Alfred – Florian Panzieri

Frank – Michael Green

Dr. Blind – Fionn Robertson

Frosch – Mike Lyle

Production:

Director – Josh Dixon

Assistant Director – Natalie Doyle

Set Design – Tommy Harvey

Producer – Alex Sikkink

Musical Director – Theo Caplan

Vocal Musical Director – Florian Panzieri

Choreographer – Natasha Agarwal

Fight Choreographer – Tommy Harvey

Costume Design – Emma Ann Hall

Die Fledermaus proved an inspired choice for Opera Warwick. This youthful company, so polished in Mozart and Monteverdi, has a flair for no-holds-barred comedy, a talent clearly evidenced in their Rossini’s Cenerentola and, more recently, by all accounts, Lehar’s The Merry Widow. Strauss’s The Bat—and we certainly got a cuddly flying mouse in this production—is the very apogee of what became the genre of Viennese Operetta. And it is so because it is musically so vividly devised, so brilliantly varied, so artful, so rapid-fire and endlessly entertaining, as it certainly was here in this staging.

It all begins in the pit. Opera Warwick has had some pretty scintillating student conductors over the years, and this time round, something that has enabled their singers—a mass of young talent—to shine, while an orchestra drawn from numerous faculties to prove its mettle. For once this year, Paul McGrath, the university’s Director of Music, took the helm, and what a revelation he proved. Always serving the music, with a beautifully inventive beat encompassing numerous gestures, always beneficial, plus a marvellous sense not just of time but of time changes—so crucial if this opera is to make maximum impact—he brought an enabling and constantly encouraging persona to bear on this kaleidoscopic score.

The collaboration between pit and stage was so especially effective because the hugely experienced McGrath, well used to working with top professional companies, has a gift for giving to cast or chorus leads of great precision and flair. At the same time, he puts fire into the orchestral players, be it violins (often), double basses or members of the finely proficient woodwind section. Everything McGrath did looked finessed, perfectly nursed, often with an accompanying smile or conspiratorial smirk: just right for this impish, tongue-in-cheek score. His pacing brought the whole production, scene after scene, alive. The violin sound was uniform, ever reliable, beautifully well tuned and strong throughout. Double basses and cellos duly skedaddled, woodwind solos shone. Time after time it was those dazzlingly perfected changes in tempo, or rather his signalling of them, rendered the more lucid by his finessed, hugely adroit manipulation of an adept small baton, that counted. The overture finished brilliantly, and from then on the show really moved. McGrath’s patent charisma counted for everything.

What also benefited the whole evening was the translation, a spirited new one (with help from translator Eve Miller) by second-year Theatre and Performance student Josh Dixon, who also directed. At no point did the text falter or droop. The vowels seemed to lie naturally and never awkwardly: the comic updates relating to modern (Thatcherite) Britain all went down well, and gave the racy dialogue added flair. The company employs a mild form of miking, something one tends to disapprove of in Opera (and even in Musicals). Yet the sound designers had the intelligence to keep this minimal. One could plainly hear the words from the stage. The enunciation from all the cast, in short, was first-class. Only two or three times did one have to strain one’s ears.

What sort of a staging were we treated to? In Acts 1 and 3 movement was somewhat restricted by the tall curtain concealing the palace set for Act 2. In the last act, the prison scene, this was scarcely an issue. At the beginning—something of a romp featuring Eisenstein and Falke, very amusingly carried off, and full of slick ideas, including wildly invading the audience—things got off to a good start. True, Tommy Harvey’s set (some chairs that looked the part, a sofa or two) was straightforward: what worked rather well was a number of nicely planned props. Meanwhile the emphasis thus fell on the actors, and Opera Warwick proved itself an ensemble who are very much determined to entertain. There were many laughs in store in Dixon’s fast-moving production.

Both first year Ross Kelly’s hyperactive Eisenstein—at times you might have taken him for Don Giovanni—and Cole McLaren-Bailey’s Falke served up some side-splitting comedy which served the show well. Each has a pleasing baritone, which hit a high point later on. In Eisenstein’s Act 3 comic sequence masquerading as the notary Dr. Blind (Fionn Robertson), whose bizarre white wig, initially abysmal, gained character once balanced precariously on Eisenstein’s head, was especially funny. Moreover, Kelly’s voice seemed to come into its own at this point, and a rather beautiful tone emerged. Falke’s sound was pleasing passim, always more sophisticated, and stylish, but it was his lilting solo (becoming ensemble) at the end of Act 2 in “Friends of mine” where the quality of support to the voice and the attractiveness of the tone became most evident. The same might be said for Ellie Popham’s feisty Rosalinda. Her amusing dalliance with singing teacher Alfred in Act 1, laced with witticisms about the National Health Service and so on, confirmed the strength of her voice, but it was the Hungarian csárdás delivered in her masked disguise at the ball (which Dixon’s staging neatly divided in half for the interval) where the full beauty of her tone quality shone through. She was Warwick Opera’s Countess in their recent Figaro, as you could hear why.

But it was when Alfred (Florian Panzieri) began to sing a spoof mixture of Puccini (and who knows what else) that realised here was a voice and delivery to be treasured. Panzieri, a 3rd Year History and Politics student, was here performing as a tenor for the first time, having previously sung baritone. You would not have thought so. This was one of the most delicious lyric sounds one has heard from a young singer in recent years. He seems to have made the transition far quicker than, say Alan Oke, now one of Opera North’s outstanding tenors, who took a time to transit successfully from baritone. Panzieri’s sound was as delicious in Act 3, where he whiles away the time in Frank’s and Frosch’s jail by singing to himself. He has those top notes, one wants to say, to perfection. This was an exciting discovery, and a new voice already mature and totally unspoilt.

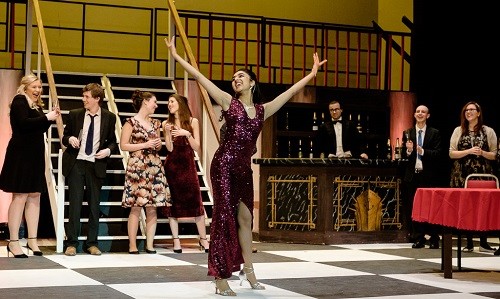

The Prince’s ballroom looked a little threadbare, even with a prominent set of steps at the rear; a few portraits or a chandelier would have been nice. But it was helped not least by two things. The moves of the chorus—many doubtless plotted, some skilfully improvised by individuals—looked pleasingly realistic, and the conversations and exchanges appeared quite genuine. The crossing of the stage horizontally in a number of moves looked highly intelligent. The 17-strong chorus, who carried this off so ably, also sang splendidly, to the extent that one wished Strauss had allotted them more. So the general context was nicely devised, and the moves of the principals were elegant and appropriate too.

At the centre of events is Prince Orlovsky. Here Ellie (Eleanor) Sterland contributed palpably to the fun. Her moves, and sometimes military stance and postures, with a well-calculated propriety and stiffness, and particularly her accent—genuinely Slavonic—made her a stylish and affable host. Her singing was a pleasure, if occasionally needing a little beefing up, but truly splendid in all three of her main set pieces, each as good as the others. The paces set by Paul McGrath always seemed to hit the nail on the head, and to suit like a glove her voice and sense of delivery. The costume department (Emma Ann Hall with Anne Peo) came up trumps here. One felt a little more flair might have helped the male characters especially early on, but the Prince and his guests seemed quite aptly attired. Perhaps one needed some variety from the constant waving of champagne glasses, but it managed to look a posh enough do.

But it was Adele (Natasha Agarwal, the wonderfully engaging Susanna in OW’s Marriage of Figaro), continuing as in Act 1 to fascinate the ear with her splendiferous coloratura, who perhaps took the laurels of the whole evening. She is such a polished singer, not to mention her delicious little self-choreographed dance at the ball, that one was entranced by her every note and gesture. She is a persuasive performer; her acting (nicely directed) was endlessly enticing. She has a persona and presence of real note, she lifts a performance to a higher level, and with Panzieri she supplied the most satisfying and impressive voice of the whole opera. Adele must be able to soar to the heights, and that Miss Agarwal can certainly do. Her close attention to McGrath’s enabling beat guaranteed that there were no hiccups in this scintillating performance. Actress and singer of equal stature, she certainly has the gift of making a character her own.

Michael Green, the company’s secretary, made of Frank, the hapless prison governor, a delightful, put-upon, much-teased character who entertained on every appearance. This was because he has a range, a complete array, of facial gestures and little twitches that portray mixed hope and despair, anxiety and determination, insistence and concession. Amiable even when others take the mickey, he engineered a different mood at every turn. More importantly, the voice was a pleasant one, both spoken and sung. He proved rather a treat.

The surprise of the evening was when Mike Lyle, a veteran member of the chorus, revealed hidden talent when cast as a broad Scottish Frosch, whose mischievous lines—partly mapped out by Josh Dixon but surely in tone mainly his own—produced a Frosch on a par with some of the best around (Frankie Howerd was a famous Frosch at ENO). He invaded the audience, wreaked havoc on a very tolerant young lady from (as it happened) the Dominican Republic, and then laid into the orchestra and conductor with mocking abuse and north of the border argot. This was an inspired bit of casting which yielded much humour. But the nice thing was that Lyle knew where to stop, and not to go too far over the top. It was a frankly professional, as well as generally side-splitting, performance.

So, a capable staging, well managed and polished so far as it went; some very attractive individual performances; and an orchestra that seemed wholly on top of every nuance. The changes in tempo, from triple time to a whole welter of 2/4 and 4/4s, is potentially a nightmare. It is one of the things that makes this opera, which is based on a Vaudeville by that most talented of duos, Meilhac and Halévy, so brilliantly varied and fast moving. In fact each section of the orchestra merits praise: the clarinets, sometimes not paired but written as two solos; the skill of the double basses at maintaining a sound foundation, especially in certain key female arias; the appealing violas, who effectively launch the opera, and round off the first scene; even the tuba, bells, tympani and bass drum, who have roles to play at a scattering of vital and comic moments. And indeed the strings altogether.

In fact, praise is to the whole, sensationally well-organised set up that is Opera Warwick. This was a finely-marshalled, frankly outstanding ensemble drawn from a University that has no Music Department. If not a universal triumph, this proved a jolly fine show with loads to relish throughout.

Roderic Dunnett

Thank you Roderic for taking the time and effort to write such a comprehensive review! It was indeed a wonderful show!