United States Tchaikovsky, Eugene Onegin: Soloists, The Metropolitan Opera Chorus & Orchestra / Robin Ticciati (conductor). The Metropolitan Opera’s Live in HD broadcast to the Odeon Chelmsford, Essex, 22.4.2017. (JPr)

United States Tchaikovsky, Eugene Onegin: Soloists, The Metropolitan Opera Chorus & Orchestra / Robin Ticciati (conductor). The Metropolitan Opera’s Live in HD broadcast to the Odeon Chelmsford, Essex, 22.4.2017. (JPr)

Cast:

Eugene Onegin – Peter Mattei

Tatiana – Anna Netrebko

Lenski – Alexey Dolgov

Olga – Elena Maximova

Prince Gremin – Štefan Kocán

Larina – Elena Zaremba

Filippyevna – Larissa Diadkova

Triquet – Tony Stevenson

Captain – David Crawford

Zaretsky – Richard Bernstein

Offstage voice – David Lowe

Production:

Production – Deborah Warner

Stage director – Paula Williams

Costume Designer – Chloe Obolensky

Lighting Designer – Jean Kalman

Video Designers – Ian William Galloway & Finn Ross

Choreographer – Kim Brandstrup

Live in HD director – Gary Halvorson

Live-in-HD Host – Renée Fleming

Deborah Warner’s staging of Eugene Onegin was first put on at the London Coliseum (review here) by its co-producer, English National Opera, before arriving at the Met in 2013. Apparently considered more a set of ‘lyric scenes’ than an opera Onegin has seven scenes and 22 numbers across its three acts. Despite its stop-start nature – too reverentially respected at the Met – Tchaikovsky employs a leitmotif-like structure spanning those acts and you hear the same recurring themes time and again, basically from Tatiana’s Letter Scene through to the final climactic duet. Wagner it isn’t, but he was clearly a major influence on its composition which occurred within a couple of years of Tchaikovsky seeing the Ring at Bayreuth in 1876.

At end of each scene Warner had the curtain descend and there was a wintry video projection. At this point the action seized up and any atmosphere created dissipated. This was compounded by the totally unnecessary sight each time of the Met’s backstage crew changing the set. Deborah Warner’s staging – with sets by Tom Pye and Chloe Obolensky’s handsome costumes – moves the story on from the 1820s of Pushkin’s original ‘novel in verse’ to a more Chekhovian period towards the end of the nineteenth century and contemporaneous with Tchaikovsky’s composition of the piece.

The opening scene is supposed to be set – according to the stage directions – in a garden of the Larin country estate and there we should meet the sisters Tatiana and Olga and their mother, Madame Larina. In this production, the first three scenes take place in what looks like a rather dilapidated conservatory looking out onto that estate through windows covered with large blinds. Peasants enter to celebrate the harvest with singing and dancing and immediately the stage looks rather cluttered. There is some strange choreography (from Kim Brandstrup) here as a young girl is thrown about and generally man-handled and – not for the last time during the opera – I wondered whether some of the dance music could have been left out. The conductor – Simon Rattle protégé and lookalike – Robin Ticciati would not agree with me because he made much of how Tchaikovsky was ‘a man of dance’. (This was one of the better backstage interviews on this occasion, because no matter how affable the Live in HD host Renée Fleming was she encountered the problem of the Russian singers’ lack of spoken English as – for some reason – she fixated on asking about the significance of Pushkin’s ‘poem’ to them.)

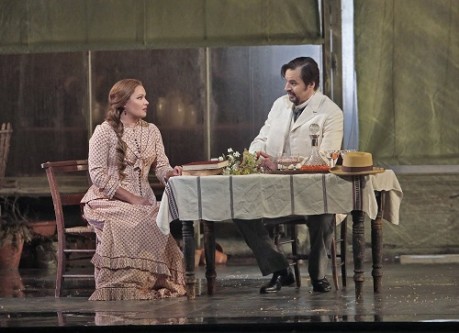

Tatiana is a dreamer lost in her books, the more free-spirited Olga has a fiancé, the aspiring poet, Lenski. He arrives with his friend Onegin, who has inherited his uncle’s neighbouring estate but has no interest in running it. Flirting with Tatiana amuses the aloof and uncaring ‘alpha male’ Onegin. This unleashes pent-up romantic urges in Tatiana which does not go unnoticed by the sisters’ nurse, Filippyevna. For the famous Letter Scene, Tatiana rashly stays up most of the night declaring her love for Onegin in writing. For some reason her more intimate conversation with Filippyevna about her childhood and marriage, as well as, the letter writing takes place in the conservatory of the first scene; as does Onegin’s subsequent rejection of her. He says marriage is not for him and he can only care for Tatiana as a brother would.

There is a suitably plush ballroom for the Act II: Onegin is bored and thinks it would be a ‘hoot’ to flirt with Olga and make Lenski jealous. The waltz is nicely choreographed and there is a lot of whirling from Onegin and Olga around the ballroom. This leads to a quarrel between the two former friends and their subsequent duel which has a suitably ominous and mist-shrouded setting and ends with Onegin somewhat reluctantly killing Lenski. For Act III’s final two scenes we are in Prince Gremin’s palatial St Petersburg house which is hinted at by some large marble-like columns. Five years have passed since Lenski’s death as Onegin has attempted to come to terms with what he did. Returning to St Petersburg he is astonished to find Tatiana married to Gremin and finally realises he is in love with her. Still in the palace – though with Zhivago-like snow falling – the opera concludes as Tatiana confesses she loves Onegin but will remain faithful to her husband and so bids the distraught Onegin farewell forever.

Eugene Onegin is full of dramatically rich music which should have a cumulative impact because of the ‘arc’ Ticciati mentioned in his interview. Why was I left relatively unmoved by it all? Difficult to say, though I suspect interrupting the scenes did not help. Another problem was that in a work about adolescence the leading roles were performed by two singers long past the age their characters are supposed to be. I believed in Peter Mattei’s world-weariness as Onegin, but was he Pushkin’s Onegin? Having been away five years Onegin declares in Act III he is still only 26! His unwillingness to commit to Tatiana actually comes more from the fact he has no need to settle down and he wants to have more experiences before he does. Netrebko’s Tatiana transformed believably into the sophisticated aristocrat turning men’s’ heads in Act III, but was never credible as the naïve withdrawn country girl starved of male attention in Acts I and II. Have no doubt the singing of both of them was exceptional: Netrebko’s intensely dramatic outpourings expressed her character’s shifting emotions very well and whetted the appetite for her future new roles as Aida, Tosca and Adriana Lecouverer, amongst others; and Mattei’s Onegin wonderfully conveyed his character’s descent from haughty cynicism to ruined, emotional wreak with a compelling, burnished baritone voice.

Almost equalling Mattei was Alexey Dolgov as Lenski and he brought great pathos and an open-hearted honesty to his Act II aria (‘Kuda, kuda vï udalilis’) which was genuinely affecting. Elena Maximova’s darkly-focussed mezzo and pert characterisation made more of Olga than Tchaikovsky allows. A former Olga, Elena Zaremba, was not an entirely secure Larina, whilst Larissa Diadkova was very good as a world-weary and caring Filippyevna. Štefan Kocán impressed as Prince Gremin and brought great dignity to his expression of love for Tatiana in Act III. However, he described himself as ‘a grey-headed warrior’ even though he looked – for whatever reason – one of the youngest of the leading characters. (I could not understand Warner’s reasoning for this if it was how he looked in the original production.) It is always difficult to comment on music heard through cinema loudspeakers, but Robin Ticciati appeared to conduct throughout with theatrical energy and warmth. He seemed to keep the orchestra, soloists and the always reliable chorus mostly on track during the dance and big ensemble numbers, whilst never moving too fast for his singers nor particularly over-indulging them.

Jim Pritchard

For more about The Met Live in HD forthcoming transmissions visit http://www.metopera.org/Season/In-Cinemas/.

Dear Dr. Jim Pritchard

I send you comment about Gremin. From FB Štefan Kocán:

Štefan Kocán:

23 apríl, 18:40 ·

Dear my facebook friends ,

I just like to say one thing about Gremin.

He is NOT old!

At the end of opera is Onegin 26 , Tatyana let’s say 20-22 (?) and Gremin is around/after 30.

Gremin in his aria only refers to an old man and to a young boy in the bloom of youth…

That means the staging of the MET didn’t felt short! …but totally in accordance with Pushkin and Tchaikovsky potrayed Gremin as an adult (not any more boy) man with an war experience.

It was a fine performance from Štefan Kocán. I understand this BUT shouldn’t Gremin therefore still look older than Onegin and Tatyana?

Thank you very much for passing this on.

Jim

Yes, Tatjana should be younger :) …..

but, it was ok performance

Who cares about age? I found it a deeply moving performance from everyone.

Agree! Just to be clear this was never a comment about the age of the performers but how the opera looked in cinema close up in relation to its story.

I agree with Maestro Kocan, who is fantastic in every role. If Gremin is an old man, then it makes no sense that Tatyana is so torn in her choice. If you have a handsome adult man, then he is real rival to Onegin. Tatyana could possibly leave an old gas bag for Onegin, but she’s married to a strong man as her husband. That’s why she is having a fit! She’s not an angel, just staying with her husband because it’s her duty. She’s a young woman with a woman’s feelings!