United Kingdom Verdi, Otello: Soloists, Royal Opera Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal Opera House / Sir Antonio Pappano (conductor). Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London, 28.6.2017. (JPr)

United Kingdom Verdi, Otello: Soloists, Royal Opera Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal Opera House / Sir Antonio Pappano (conductor). Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London, 28.6.2017. (JPr)

Cast:

Otello – Jonas Kaufmann

Desdemona – Maria Agresta

Iago – Marco Vratogna

Cassio – Frédéric Antoun

Roderigo – Thomas Atkins

Emilia – Kai Rüütel

Montano – Simon Shibambu

Lodovico – In Sung Sim

Herald – Thomas Barnard

Production:

Director – Keith Warner

Set designer – Boris Kudlička

Costume designer – Kaspar Glarner

Lighting designer – Bruno Poet

Movement director – Michael Barry

Fight director – Ran Arthur Braun

Most critics – for some reasons best known to themselves – will not watch the live opera transmissions to cinemas, especially those from the Met. This Seen and Heard site is almost unique in reviewing these broadcasts. For most commentators it would have provided more points of reference when discussing Keith Warner’s new Otello if they had seen Bartlett Sher’s recent new production at the Met (review click here). It was a much better ‘character study of jealousy and betrayal rather than the exploration of the outsider that is the basis of Shakespeare’s original play’. There was an ingenious set able to illuminate the character’s public and private behaviour, their outer and inner conflict, as well as, the passage of time, much more convincingly. In Warner’s staging Iago gossips with Cassio to bring him some of the proof he needs of Desdemona’s infidelity, and Otello is not under a table, behind a door or listening through a window but high above them on a platform. (I felt sorry for Jonas Kaufmann who was clamped on up there and I was as nervous for him as he seemed due to the height.)

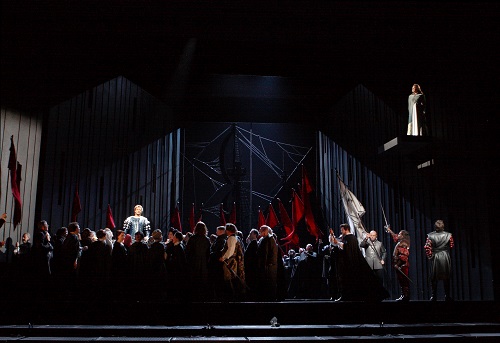

Boris Kudlička’s set – basically two huge side walls pointing inwards with movable Moorish-style lattice screens – brings no real sense that we are supposed to be in Cyprus ‘at the end of the 15th century’. Not much changes in what we see during the 2½ hour opera. Some elements of the walls and floor do move – especially the more drunk Cassio becomes in Act I – and a long bench later becomes the table on which Otello is planning his next campaign in Act III; an expensive looking large Lion of St Mark statue quickly crosses the stage during this act and reappears in pieces in Act IV. Actually, from the appearance – another fleeting one – of a vast ship not long after the start, I began to ponder that this set and all the (mostly) stygian gloom of Bruno Poet’s lighting could have been used even better for Der fliegende Holländer or perhaps Lohengrin, especially when Desdemona’s all-white designer bedroom appears for the final scene. For some reason characters emerge from below the stage and as Otello mentally disassembles at the end of Act III a part of the set turns to reveal some graffiti on it. When required by Verdi the booming chorus basically just frame the action and something should be done about how noisy they are clomping around the set.

Antonio Pappano, his musicians and singers, are all in can belto mode from the very first note and this is perhaps the loudest Otello I have ever heard. Due to there being just one interval the evening flew by quickly thanks to Pappano’s viscerally exciting sense of propulsion. However, there was relatively little subtlety or refinement until some of the quieter pensive moments in the final two acts. The orchestra played well – as they usually do for their music director – but there seemed some instances when the ensemble between pit and stage could have been better.

Warner begins Acts I and II with Iago spotlit front and centre stage, and Acts III and IV similarly, but it is now Otello. The director’s focus is clearly on these two central characters and the rest are mere ciphers, including Desdemona. Marco Vratogna has a magnetic presence and embodies Iago perfectly for me. This Iago is an aggressive, shaven-headed bully, bringing tremendous menace to his ‘Credo’ and in everything he did. Desdemona is usually sung as one overarching limpid stream of vocal delight but Maria Agresta is not that type of singer it seems. This Desdemona know she has done nothing wrong and stands her ground. Agresta’s singing mostly reflected that with her full-on, rich, soprano sound more dramatic than lyric. Despite this her introspective, heartrending, singing of the ‘Willow Song’ and ‘Ave Maria’ in Act IV were her highlights. Frédéric Antoun displayed a cleanly produced tenor voice as Cassio, and there were excellent contributions from Simon Shibambu (Montano), Thomas Atkins (Roderigo), In Sung Sim (Lodovico) and Kai Rüütel (Emilia). In general, they all made this Otello a vocal performance to treasure.

There was endless speculation from many – me included – as to whether Jonas Kaufmann would turn up for his first ever performances in the title role of Verdi’s late masterpiece. Everyone seems to want to compare him to Jon Vickers and Plácido Domingo, just two of his famous predecessors at Covent Garden. I saw both of them of course but prefer to dwell – on this occasion at least – on the ‘here and now’ rather than the past. I also don’t want to worry too much about a further dilution of the usual tradition of having a white singer made-up to be a dark-skinned Otello. However, what that usually achieves is to highlight Otello’s difference to all those surrounding him, a crucial aspect of the story. Without this he just becomes a fairly ‘stock’ character; someone just lacking the ‘backbone’ – or the emotional strength – to avoid being easily manipulated by Iago just because he is resentful that Cassio has been made captain ahead of him by the ‘outsider’. For me the lightly-bronzed Kaufmann was too Byronic. I never believed in him as the great general and a hero to the Venetians as that would have made his descent all the more affecting. His love for Desdemona comes and goes with a blown kiss and the great Act I closing duet, and for the rest of the opera he just seems to be an overgrown sulky adolescent.

As for Kaufmann’s voice he gets through the role ok, but the demands it makes on him means he is wary at the moment of losing his cool as a performer and taking the character to the emotional edge of a ‘true’ Otello. His voice overall is so darkly baritonal that in the impassioned duet with Iago (‘Si, pel ciel’) Vratogna sounded as if he had the higher voice at times. Kaufmann’s chest register was occasionally unsupported, there were some stentorian top notes, and a tendency to croon when he lightened his voice such as for ‘Dio! Mi potevi scagliar’. He overcomes any doubts that he might be overwhelmed by the sheer volume of orchestral sound by singing mostly from the front of the stage. It is a thoroughly accomplished performance but no more than that. This seemed to be recognised by the audience who did not celebrate his performance any more than those of Agresta or Vratogna.

Jim Pritchard

For more about performances by the Royal Opera (click here).