United Kingdom Sondheim, Follies: at the Olivier Theatre, Royal National Theatre, London, 7.8.2017. (JB)

United Kingdom Sondheim, Follies: at the Olivier Theatre, Royal National Theatre, London, 7.8.2017. (JB)

In these days where every headline screams doom and gloom, the feel-good factor of Follies is joyfully therapeutic.

On 5 October I shall be reporting from the Place in London, where Neil Bartlett, François Testory and Phil Von will be performing Medea, Written in Rage: open-heart surgery on the doom and gloom syndrome: a show probably not for the faint-hearted, I’d guess. Meanwhile, just don’t expect to pick up a ticket any time soon for Follies, though I do have good news, wherever in the world you may be, for those who wish to see the show. To be given at the end of this piece.

That shocking forte chord which opens the overture of Follies (called prologue in the score) may not quite contain all twelve notes of classical tonality, but it contains most of them. The point is its appropriateness: it arrests us. A cheap trick, you may think. But as Sondheim well knows, a cheap trick is not cheap in the right context. His work is full of this skill. It is often forgotten that he had studied composition with Milton Babbitt, who certainly provided him with the technique for serial (twelve-tone) composition. Sondheim absorbed the technique to mostly abandon it (as Britten would do later and Harry Birtwistle and Max Davies later again). As Anthony Burgess (himself a composer as well as novelist) never tired of pointing out, if you abandon key-centre, you abandon joy: it may be interesting but it’s as neurotic as hell. All Sondheim’s work is gloriously tonal but the serialism gets used as a dramatic threat to that comfort zone. I shall argue that this drama is sometimes overused in Follies.

Stephen Sondheim’s orchestration is as fine and inspired as any living composer. It announces its mastery in the opening scene, especially in Waiting for the Girls Upstairs and Rain on the Roof. It owes some of its inspiration unashamedly to Rimsky Korsakov. Rimsky’s colourful scores often have original touches of mischief in their inventiveness, especially in the percussion department. Sondheim picks this up and runs with it, so to speak, so invoking a genial, childlike naughtiness. The Sondheim instrumentation caters beautifully for jazz combinations. The musical conversations between the three trumpeters – Owain Harries, Sebastian Philpott, Dave Hopkin – was one of the greatest aural delights of the evening, their instruments muffled with scores of devices to produce that unique mocking seriousness which is the hallmark of trad jazz.

And while I’m with the orchestra – twenty very busy players – congratulations to its conductor, Nigel Lilley, whose perfect balance was admirable, in the foreground when they were the protagonists, and the background when they were accompanists, though never so much in the background for us to miss the finer points of Sondheim’s details. The programme does not make clear who should be credited for the (orchestra’s) amplification, so I’m unable to name this operator of unimpeachable professionalism. Paul Groothuis is named as Sound Designer. If this be he, my hat off to him.

One musical detail which failed badly for me, had better be reported as quietly as I can manage. The two adult pairs – Sally Durant Plummer and Phyllis Rogers Stone (Imelda Staunton and Janie Dee) and their two flames, Benjamin Stone and Peter Forbes (Philip Quast and Peter Forbes) are of the 1930s/40s Follies and mirrored in the story by their younger selves – more or less from “today”: Young Sally and Young Ben (Alex Young, Adam Rhys-Charles) and Young Phyllis and Young Buddy (Zizi Strallen and Fred Haig). The dramatic possibilities of conversations with younger selves, are of course, legion. But Stephen Sondheim does not have the psychological insights of George Elliot, where a casual remark can illuminate an unexpected quality of a character. Worse, Sondheim is worthless as an armchair philosopher. Dull, in fact. I found myself looking at my watch. How much more of this tripe? The descents into sentimentality I found embarrassing and crass. There. I’ve said it.

But I also suggest you might take no notice of my particular prejudices. The audience totally disagreed with me. Sally Durant Plummer’s sad, unfortunate love affair with Ben is recounted with the moral seriousness of Violetta’s Ah forse lui in Act I of La traviata. But Violetta, you will recall, is dying of consumption, and besides, Stephen Sondheim is not Giuseppe Verdi. It is his attempt to be Verdi which is the embarrassment. All the same, Imelda Staunton delivered this trash with such conviction that the audience applauded her to the rafters. The theatre has not given us a photo of her in this scene; a pity, she sat still at a dressing table only half facing the audience but vocally impressive throughout. Here is what she looked like in an earlier part of the musical.

(c) Johan Persson

Ms Staunton had said in an interview that she was concerned that she might not be up to the tap dancing which the role calls for. She need not have worried. Years ago, Wayne Sleep told me that when he wanted tap dancing he would fake the steps for the boys, for girls alone were taught this skill (he meant at the Royal Ballet School from where he came himself). This is what choreographer, Bill Deamer has done here for all who are not principally dancers: faked it. To the untrained eye it is remarkably convincing, not least because the entire company are so completely in the spirit of the romp.

Di Botcher as Hattie Walker, got the stop-the-show triumph of the evening for the casual, vulgarity and all the fun that brings when it’s played straight as here. Broadway Baby is Sondheim lyrical music and wit at its best. And this is the song that most of the audience already knew.

Josephine Barstow, wearing an elegant evening gown (Costume Supervisors, Irene Bohan and Helen Johnson) and with a fifty-year glorious operatic career behind her, gave the most impressive account (especially of some perfectly placed high notes) of Heidi Schiller, the snobbish wife of the great man.

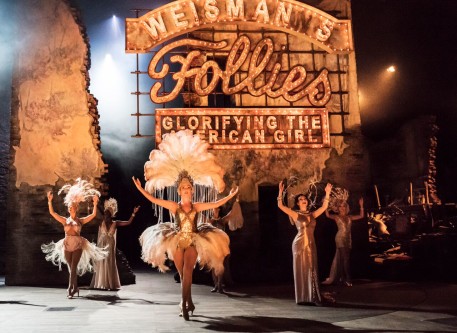

Maybe the greatest spectacle of all was the girls of the Follies themselves, whose energy equalled the extravagance of their dazzling costumes.

Sondheim’s talent in comedy is unsurpassed on today’s scene, for words, music and technical know-how. To my eyes and ears, he comes unstuck when he ventures into life’s darker corners. This is not just my view alone. But there are many who will not go along with it.

Jack Buckley

Follies will be broadcast by NT Live to cinemas in the UK and internationally on Thursday 16 November. For more information click here.

thanks for review jack buckley! i have 2 canadian friends visiting London this week and will urge them to try desperate measures to get tickets! they need cheering up what with Trump in States and Brexit in Europe – cheering up is what is needed.