United Kingdom Verdi, La forza del destino: Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of Welsh National Opera / Carlo Rizzi (conductor), Theatre Cymru, Llandudno, 21.4.2018. (RJF)

United Kingdom Verdi, La forza del destino: Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of Welsh National Opera / Carlo Rizzi (conductor), Theatre Cymru, Llandudno, 21.4.2018. (RJF)

Cast:

Leonora – Claire Rutter

Don Alvaro – Gwyn Hughes Jones

Preziosilla/Curra – Justina Gringytė

Don Carlo di Vargas, – Luis Cansino

Il marchese di Calatrava / Padre Guardiano – Miklós Sebestyén

Fra Melitone – Donald Maxwell

Mastro Trabuco – Alun Rhys-Jenkins

Alcade – Wyn Pencarreg

Production:

Director – David Pountney

Set designer – Raimund Bauer

Costume designer – Marie-Jeanne Lecca

Lighting designer – Fabrice Kebour

Choreographer – Michael Spenceley

After the premiere of Un ballo in Maschera, Verdi’s 23rd opera in Rome, and with no contracts pressing, the Rome impresario, Jacovacci, attempted to persuade the composer to sign a contract for a new opera. Verdi was 46 years old and had composed his twenty-three operas in 20 years. Because of the trouble with the censor in Naples where Un ballo in maschera should have been staged he had not faced the pressures of composition for nearly a year. He announced to a small circle of friends, including Jacovacci, that he had given up composing and intended to return to his farm and enjoy the fruits of his labours in a more relaxed manner.

However, the fight for the unification of Italy was won and Cavour, the father of that fight, persuaded Verdi to stand for Italy’s first National Parliament. He did so and was elected. Verdi attended assiduously until Cavour’s premature and untimely death when his interest declined. Meanwhile, in December 1860, whilst Verdi was away in Turin on political business, Giuseppina received a letter from a friend in Russia. Also enclosed was an invitation from the great Italian dramatic tenor Enrico Tamberlick, who Verdi knew and admired. Acting on behalf of St Petersburg’s Imperial Theatre the letter invited Verdi to write an opera for the following season. Despite the likelihood of temperatures of minus 22 degrees below zero, the prospect of a visit to Imperial Russia appealed to Giuseppina and she promised to use all endeavours to try and persuade Verdi to accept. Whether it was her skills of persuasion, the fact that he was missing the theatre, or the conditions of the contract, particularly of a large fee that would help fund the major alterations at his Sant’Agata estate, Verdi eventually agreed.

The dark core of Rivas’s drama involves scenes set among the common people including a gypsy fortune-teller. Verdi lightens the dark plot, with its multiple deaths somewhat further than the play. To do so he uses a scene from Schiller’s Wallenstein’s Lager involving a panorama of life in a military encampment including soldiers, vivandières, gypsies and a monk who preaches in the funniest and most delightful manner in the world. The monk becomes Melitone in the opera and which is often seen as a precursor to the eponymous comic role in his great final opera, Falstaff. What La forza del destino does demand are full toned Verdi voices. It is no opera for upstart lyric voices. This is best illustrated by the fact that when Verdi and his wife made the long journey to St. Petersburg for the premiere in December 1861, and found the soprano contracted for the role of Leonora to be ill, it was not possible to find a substitute singer from the company roster and the whole production was postponed for one year. When the opera was eventually premiered on 10 November 1862 it was a success with the Tsar attending, inviting the Verdis to his box and later investing him with the highest state honours.

Verdi, however, was not wholly happy about the ending of the opera with its depressing multiple deaths in the final scene. Aware of its vocal challenges, he also withheld the score from theatres that he considered incapable of doing it justice. He had recognised the need for alterations early on when he transposed the tenor aria in Act III downward on the basis that only Tamberlick was capable of meeting its demands. Verdi eventually got around to a revision when his publisher, Ricordi, proposed performances at La Scala. The revised La forza del destino, the version performed in this performance, was premiered at La Scala on 27 February 1869. The premiere marked a rapprochement between Verdi and the theatre by which the composer had forbidden any of his operas being premiered there since his seventh, Giovanni d’Arco in 1845!

The alterations of the score of La forza del destino from the original 1862 version are significant rather than major. They involve the substitution of the prelude by a full overture, which nowadays is often played as a concert piece, a major revision of the end of Act III and including the removal of the demanding tenor double aria. Further, the whole final scene of the opera is amended by which the triple deaths are avoided, being replaced by Padre Guardiano’s benediction as Leonora dies and Alvaro is left alive.

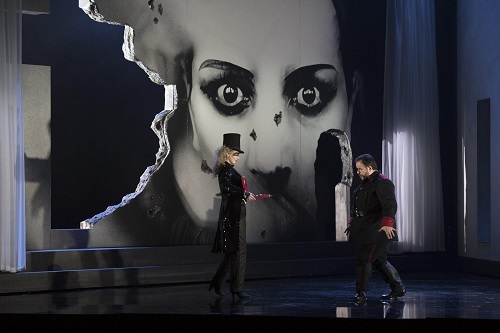

Conductor Carlo Rizzi, who has twice been musical director of Welsh National Opera, conducts the performances of La forza del destino this season. Internationally renowned, not least for his interpretations of the operas of Verdi, it is, strangely, his first time conducting this work, and which says something of the rarity of performances. This rarity is as much related to the demands it places on the solo singers as on the challenges of production of the diverse, some say rambling, story. In this performance Rizzi’s feel for the Verdian idiom shone through from the opening chords. The director David Pountney and his team have gone for very large movable screens with doorways, shapes, faces, words, a rotating pistol and the like, so as to hopefully facilitate comprehension of the complexities of the unfolding story. It is to be regretted that they are not wholly successful, albeit it is possible to follow the intentions in the first two acts whilst unnecessary blood smearing and strange costumes for Preziosilla’s vivandières in Act III made little sense. In comparison, the simplicity of Act IV is under directed and loses the poignancy of the deaths portrayed within the orchestral music and Padre Guardiano’s response.

This Llandudno performance was the last of the series and the end of the season. Mary Elizabeth Williams who, according to critics, had made a big impression as Leonora was not available and was replaced by Clare Rutter who had sung Tosca the previous evening. Some challenge for any singer. Suffice to say that her achievement should go down in WNO’s annals. Her aria in the last act may have lacked the ultimate Verdian shaping of her predecessor, but it was no mean achievement in the circumstances. She must have been vocally quite tired, after all the role of Tosca is no two-verse sampler for greater things! As her would-be lover, local boy Gwyn Hughes Jones, a long time WNO favourite and stalwart, showed some signs of strain at the top of his essentially lyric-toned dramatic voice of which he needs to take more care, particularly when it is not always necessary to sing forte when some more graceful phrasing and softer tone would – in my opinion – be at least as appropriate and effective. His loyal followers raised the roof of a full house and went home well pleased. As the adversary seeking the death of Alvaro, the Spanish baritone Luis Cansino sang with good variety of well-modulated tone as he portrayed the malevolence and hate of the Calatrava clan for Don Alvaro and his lineage. Padre Guardiano gives Leonora refuge and Miklós Sebestyén – doubling as the shot Il marchese di Calatrava in Act I – sang with appropriate gravitas and sonority of tone. As the monk Fra Melitone, Donald Maxwell acted the role well but no longer has the requisite vocal resources even for a comprimario role. As Preziosilla, Justina Gringytė was given an unusual costume yet fulfilled the Pountney’s vision whilst also singing with exemplary characterisation, her stirring ‘Rataplan’ was worth waiting for.

To leave without a mention of the chorus would be seriously deficient. Their rending of the inspired spiritual music that the composer wrote for Leonora’s entrance to her refuge, the lovely ‘La Vergine degli Angeli’, and as stirring soldiers, gave them opportunity to impress and the audience to appreciate their consummate skill.

Robert J Farr

For more about WNO in 2018/19 click here.