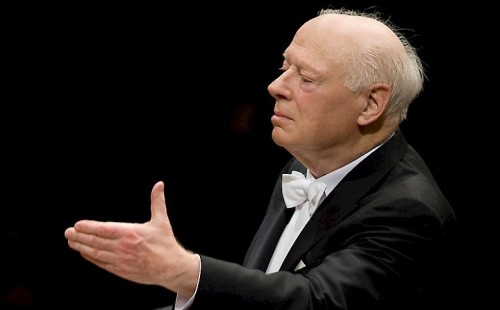

Switzerland Mozart, Bruckner: Till Fellner (piano), Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich / Bernard Haitink (conductor), Tonhalle Maag, Zurich, 20.9.2018. (CCr)

Switzerland Mozart, Bruckner: Till Fellner (piano), Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich / Bernard Haitink (conductor), Tonhalle Maag, Zurich, 20.9.2018. (CCr)

Mozart – Piano concerto No.22 in E major, KV 482

Bruckner – Symphony No.7 in E major

An obsessively devout man from the Austrian countryside who in the first several decades of his life wrote hours and hours of huge and undervalued orchestral music, before finally being taken seriously as a symphonic composer at 60: Bruckner. A bourgeois son of Amsterdam who achieved success with his conducting before the age of 30, renown before 40, and who has been at the forefront of classical music in Europe and abroad for fifty years: Haitink. Whatever binds these two souls so deeply, it was on scintillating display this week at the Tonhalle in Zurich during two concerts of Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony, in music that will ring in my ears and heart for years to come.

I would be perfectly happy to have attended a concert of only the Mozart piano concerto, so that I could spend this review telling you all about how splendid Till Fellner’s piano playing was: his gently authoritative tone, his sovereign solo passages that integrated so lovingly back into the whole, the modest and then entirely unprecious playfulness in his third movement build-up towards finally expansive dynamics, in which his two hands gradually let themselves upstage the work of the orchestra behind him, what with their sheer elegance and delight. I would tell you about flutist Sabine Poyé Morel and how sweetly she and Haitink led Mozart’s woodwind passages through their own concert-within-a-concert in the andante. (Morel and the woodwinds were stupendously good in the Bruckner, too.) I would praise the Tonhalle Orchestra as a whole for its clear balance of sound, particularly in the warm low strings.

But just as you might not spend most of what could be your final visit to the Louvre lingering in front of Titian’s portrait of François I, perfect though it is, but might instead devote what time you have to Poussin’s Four Seasons, so must I turn to the Bruckner and make the case that this music, played this way, was as vital as music can be.

Bruckner’s symphonies may be accused of being stoically excursive, of plodding through too many consecutive rounds of themselves, as if his aim were to transpose the Potemkin Steps into sound. Put aside the question of whether this reputation is the result of caricature, or various conductors’ interpretations, or Bruckner’s actual music. Haitink and the Tonhalle Orchestra found a harmony of scale for the Seventh Symphony that allowed them to build it theme by theme, movement by movement, into a perfect whole.

From an ethereal three-octave entrance in the celli, through dense horn sequences made to shine like strings, to monumental tutti climaxes arrived at organically: one never had the feeling that any passage or instrument was out of proportion to an ever-accumulating entity. What sort of mastery goes into that, what sureness of touch was 89 year-old Haitink summoning throughout this massive arc of music to keep it always taut and fresh? Was it the ever-so-slight gliding in the strings, in full embrace of the symphony’s lyricism? Or the ever-so-slight rubato you feel but don’t hear? The no-nonsense overall tempi, with the adagio not too slow and the scherzo not too fast? The unerring dynamics shifting between winds and strings and (mostly) horns? In over an hour of music, there was a constant clarity of instrumentation amidst the grandness of sound.

This wasn’t plodding. It was like viewing sound through a kaleidoscope, but one that only turns a few degrees a minute, presenting you with a concentration of colour that you would otherwise miss in its saturation.

The first movement, Allegro moderato, was exhilarating in the righteousness of its coda’s finale, but arrived there via Haitink’s patient intensity throughout the exposition of different subjects, including a marvellous passage of harmonic unrest in the winds. The Adagio was miraculous. The credit is all Bruckner’s, but consider what it is like to watch the old, sophic conductor sit down after initiating the movement’s first climax, only for him to stand back up as the chromaticism rears it towards another – one couldn’t help but meditate on the devotion and the reverent labour, weary satisfaction, life’s work. Haitink was here giving us consummate Bruckner, and Bruckner was bowing, though not submitting, to his idol Wagner, and above it all was something far greater than any one man. A cymbal clash, a triangle and a throbbing pinnacle later, I cannot have been the only one in the audience left shaken by its affecting ardour.

There were moments in the third movement’s trio where the architecture of the thing seemed to slacken, and its logical tension against the galloping Scherzo seemed impossible to maintain. There were moments in the fourth movement when the bass tuba was piercing to the point of rupture, and the four walls of the Tonhalle Maag did not want to fit the full force of all the horns.

In emotional terms, however, the plinth of the first two movements kept the momentum in place throughout the final two. The radiance and drama of the finale stood abreast the other arch-triumphs of the piece; not above them, but as their inevitable and fully-animated peer.

This concert might well have been an instance of modern audiences going through the ritual adulation of 19th century music, what critic Alex Ross (a Bruckner devotee) mocks as our insistence on a séance, at the expense of something newer. Those who tire of it would suggest that all that’s missing is incense and sermons.

But the conductor here is no mystic obscurantist. Bernard Haitink, instead of tugging you through a swirl of music, presents Bruckner’s symphonic structure so lucidly that you see it emerge before you. First it stands there, then it envelops you, and by the end you cannot help but embrace the quake it leaves you with.

Casey Creel