United Kingdom Gershwin, Porgy and Bess: Soloists, Actors, Chorus, Orchestra of the English National Opera / John Wilson (conductor). London Coliseum, 11.10.2018. (MB)

United Kingdom Gershwin, Porgy and Bess: Soloists, Actors, Chorus, Orchestra of the English National Opera / John Wilson (conductor). London Coliseum, 11.10.2018. (MB)

Cast included:

Porgy – Eric Greene

Bess – Nicole Cabell

Crown – Nmon Ford

Serena – Latonia Moore

Clara – Nadine Benjamin

Maria – Tichina Vaughn

Jake – Donovan Singletary

Sporting Life – Frederick Ballentine

Production:

Director – James Robinson

Set designs – Michael Yeargan

Costumes – Catherine Zuber

Lighting – Donald Holder

Choreography – Dianne McIntyre

Video – Luke Halls

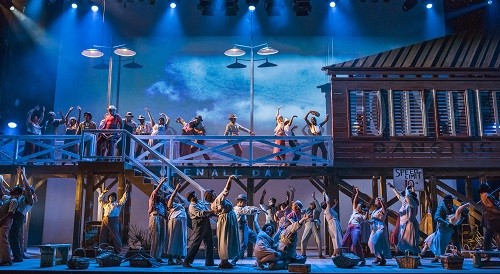

In a new production by James Robinson, conducted by John Wilson, ENO performs Porgy and Bess for the first time. On the opening night it was very well received, in many ways rightly so – although I had my doubts too, especially earlier on. I shall come to those later, but first let me say what a joy it was not only to hear such an array of fine vocal performances but also to see such fine, committed, sincere acting from an ensemble of singers and actors, many making their debuts with the company, brought together specifically for this purpose.

If there were occasional slight shortcomings, not least a little too much occluded diction from Nicole Cabell as Bess, they were more than made up for by that strength of ensemble. Cabell’s performance was otherwise strong – strong in portraying vulnerability, even helplessness, that is – and was well matched by the humanity of Eric Greene as the ‘cripple’, Porgy. Nmon Ford’s toxic masculinity, as we should now call it, as Bess’s former lover, Crown, proved an object lesson in the marriage of words, music, and stage presence. The drug dealer Sporting Life’s insidious, irredeemable amorality, his ‘lowlife’ quality, to borrow from the text, was memorably captured and communicated by Frederick Ballentine. Tichina Vaughn and Latonia Moore sang their hearts out and wore their not uncomplicated consciences on their sleeves as Maria and Serena. I could doubtless continue down the cast list, but should end up merely replicating it.

There was no gainsaying, moreover, the excellence of the ENO Orchestra, which was surely enjoying itself greatly. Likewise no one could argue with the results obtained from them by John Wilson: a film-score sheen second to none, and certainly not just from the strings. At least no one could in terms of getting what he wanted, something I have little doubt would and should be considered ‘authentic’ by those who care about such matters. For me, however, there were times when something a little more variegated would have been welcome. It is a lengthy opera, too lengthy for its material; generally slow tempi, married to almost unrelievedly opulent sound, exacerbated rather than relieved. There were, of course, passages of great incisiveness too. A few more gradations in between would have done no harm. Or would that actually have been possible? I cannot, I am afraid, hear this to be the masterpiece some claim it to be. Even if it were cut considerably, that still leaves something of a problem in a ‘symphonic’, better connective, ambition on Gershwin’s part that is at best intermittently realised. He is surely more a composer of songs than a symphonist, or indeed a post-Wagnerian musical dramatist, whatever apologists might claim to the contrary. Moreover, musical characterisation is often weak, at least earlier on. By the second act, the composer seems to have progressed considerably. Earlier on, he seems far better at communicative atmosphere, at dramatising events.

There are many opera scores, however, that fall short of Figaro, Parsifal or Wozzeck. We tend for the most part to take them for what they are, rather than exercising ourselves unduly about what they are not. (Or if we do not, it tends to be indicative of some other problem we have with them, whether intrinsic or of taste.) More of a difficulty, I think, lies in the libretto and, more generally, in the (doubtless well-intentioned) racial and gender stereotyping – one might well put it considerably more strongly than that – of the work as a whole. It is there that a production should come into its own, offering a critical stance or at least an awareness of the problems. Robinson’s blithe production, however, almost screams ‘Made for the Met’. (This is a co-production not only with New York but Amsterdam too.) It is well executed, not least on account of Dianne McIntyre’s choreography, but appears either stuck in a time warp or better suited to expectations geared towards a ‘West End spectacular’. Following the ineptitude of ENO’s current Salome, there is something, indeed much, to be said for basic, wholesale competence. That is surely, though, no excuse for flattering an audience into thinking this a matter of harmless ‘entertainment’.

Mine will, I am sure, be a minority report – and I repeat that there is much in a straightforward fashion to enjoy, should enjoyment be one’s sole or principal criterion. As the opera is what it is, so am I who I am. I increasingly find it difficult to take theatrical performances that might well have looked splendid half a century ago and might even do so on film now, yet which claim to be of the here and now. Too much dramatic water has passed under the bridge. Moreover, whilst I try to keep an open mind, my ears are not the same as everyone, or indeed anyone, else’s. When, for instance, I hear the banjo song, ‘I got Plenty o’Nuttin’,’ I think, doubtless idiosyncratically, of Blaze’s ballad from Peter Maxwell Davies’s The Lighthouse. That says nothing about either, if a little about me. Why mention it, then? Only as a banal illustration of our coming to artworks – not only to artworks – from different standpoints and situations.

Perhaps, knowing as I do of Schoenberg’s admiration for Gershwin – more circumscribed than some would allow, yet no less genuine for that – I wanted too much to listen with (post-)Schoenbergian ears and found myself a little disappointed. It has real virtues and certainly stands a good few notches above the fashionable bloated nonsense of Korngold and friends. Any reservations I entertain are unlikely to prevail over someone who finds more in the work than I do, nor am I seeking to persuade, merely to try to account for my own more equivocal reaction. Perhaps I should find more in a subsequent performance; perhaps it is simply not for me. If it is for you, and if you do not mind what is to my mind an absurdly ‘traditional’ style of staging, then you will find much to enjoy. I cannot help but wish, however, that the production had shown the courage to adopt so much as a point of view or to interrogate the work, to ask what it might fundamentally be about. That, surely, would have been to take it as seriously as Gershwin’s ambition demands.

Mark Berry