United States Verdi, Rigoletto: Metropolitan Opera Chorus and Orchestra / Nicola Luisotti (conductor), Metropolitan Opera, New York, 12.2.2019. (RP)

United States Verdi, Rigoletto: Metropolitan Opera Chorus and Orchestra / Nicola Luisotti (conductor), Metropolitan Opera, New York, 12.2.2019. (RP)

Production:

Director – Michael Mayer

Set designer – Christine Jones

Costume designer – Susan Hilferty

Lighting designer – Kevin Adams

Choreographer – Steven Hoggett

Revival Stage director – Gregory Keller

Cast:

Duke – Vittorio Grigolo

Borsa – Scott Scully

Countess Ceprano – Samantha Hankey

Rigoletto – Roberto Frontali

Marullo – Jeongcheol Cha

Count Ceprano – Paul Corona

Monterone – Robert Pomakov

Sparafucile – Štefan Kocán

Gilda – Nadine Sierra

Giovanna – Jennifer Roderer

Page – Catherine MiEun Choi-Steckmeyer

Guard – Earle Patriarco

Maddalena – Ramona Zaharia

A surprising number of people didn’t heed the dire warnings from the National Weather Service and turned out for the opening night of this run of Michael Mayer’s Las Vegas Rigoletto. And while it may have been cold and icy outside, it was sizzling inside the Metropolitan Opera. The production, first seen in 2012, combines the hedonism and violence of The Godfather with the urgency of West Side Story while doing full justice to Verdi. The action transfers smoothly from sixteenth-century Mantua to Vegas in the 1960s, which gives an appropriate edginess to this gritty tale that is harder to achieve in the soft gauze of a period staging.

A luxurious hotel casino substitutes for the Duke’s palace. Cigarette girls in feathers amble about the men, who are crowded around gambling tables and slot machines. Monterone is an Arab businessman with armed thugs as body guards, who can’t prevent him being killed in full view of everyone. A riot of colorful neon signs fills the stage; when first illuminated they provide an indisputable wow factor. Elevators on either side of the stage take Rigoletto and his daughter, Gilda, to their home and provide easy access for the men who abduct her. Watching the floor indicators light up as the elevators ascend and descend added to the tension.

Sparafucile’s hangout is a strip club where a topless girl poll dances, taking a break to step out and service a bashful client. A vintage Cadillac bearing a vanity plate with its owner’s name is parked out front; the plan is that Sparafucile will stash the Duke’s body in its trunk. The sky is full of jagged, abstract neon lines that are synchronized to flash with the music in the storm scene, with each electric pulse intensifying the sense of foreboding. It was the most deftly executed and effective of the design elements.

Mayer’s concept sticks pretty close to Verdi. It’s clear to see why the libretto, based on Victor Hugo’s play Le roi s’amuse, made mid-nineteenth-century Venetian censors skittish prior to its premiere in 1851. Such items are fodder for today’s media, hardly prompting a raised eyebrow from anyone, but portraying the elite as lascivious, duplicitous and bloodthirsty was a different matter then.

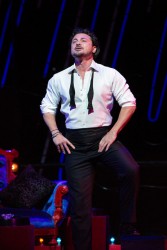

Tenor Vittorio Grigolo is a stage animal who electrifies an audience with his voice and charisma. Dark and handsome, he cut a dashing figure in a white dinner jacket that he removed every time he had something big to sing, which occurs fairly regularly in Rigoletto. He sings big too. There is an immediacy to his voice that grabs you, and not only when he is on overdrive belting out high notes. It is also present when he is singing softly and caressing a vocal line. If Grigolo weren’t such a convincing, ardent Romeo, it wouldn’t be such a letdown to discover the Duke is a cad.

Nadine Sierra could as easily have been singing ‘I feel pretty’, another innocent, sheltered girl whom love smacks in the face with tragic consequences. She was Gilda, however, and not Maria, but it is partly those associations that gave this performance its grounding in reality. Sierra took a while to warm up but, overall, her coloratura, trills and amazingly long phrases were spellbinding. If all Gildas sang the cadenza of ‘Caro nome’ on their backs, maybe they too would produce ravishing sotto voce lines and clear, pinging high notes. The duets with her father were her best dramatic moments and displayed the warmth and richness of her voice.

The title character is Rigoletto, however, and without him it would just be another story of doomed young love. Wearing a button-down sweater instead of a court jester’s costume and makeup, and with only the slightest suggestion of a hump, baritone Roberto Frontali was a bundle of malevolence and paranoia. In a world where mere vocal, or even physical, size equates to Verdian stature, Frontali’s tightly coiled baritone, with its piercing, penetrating sound, is the real thing. He seethed with rage at the onset of ‘Cortigiani, vil razza dannata’ as he denounced the courtiers and their vile deeds, dissolving into frantic, tearful pleading as his desperation mounted.

Sparafucile was Slovakian bass Štefan Kocán. Tall, lean and sinister with a dark, sparkling voice, he was an efficient assassin for hire, dispatching Gilda with repeated, shockingly violent knife thrusts. Moments later, he caressed and kissed his sister in a most unbrotherly manner before releasing her for an assignation with the Duke. Tall, sultry and beautiful, mezzo-soprano Ramona Zaharia made a notable house debut as Maddalena.

Fine voices and detailed characterizations were also found in the supporting roles. Rigoletto’s duplicitous housekeeper, Giovanna, was the excellent Jennifer Roderer, who ends up drugged and sprawled on an elevator floor as Gilda is whisked off in an elaborate Egyptian mummy case by her abductors. Samantha Hankey, with just a few lines to sing as Countess Ceprano, made an impact in a platinum-blond wing and skintight, sequined dress à la Marilyn Monroe. Bass-baritone Jeongcheol Cha as Marullo was among the most vivid and sinister of the Duke’s entourage, while Robert Pomakov as Monterone thundered his rage over the Duke’s seduction of his daughter in a particularly clear, resonant bass.

In the pit, Nicola Luisotti was acutely attuned to the dynamic shadings and phrasings of the singers. His long arms stretched over the orchestra, sculpting entire passages with no detail left to chance. Balance was ideal throughout. The men of the chorus sounded wonderful, as did the orchestra. As is generally the case at the Met, the loudest ovations were reserved for them.

Rick Perdian