United Kingdom Bach, Johannes-Passion: Reinoud Van Mechelen (Evangelist), Rachel Redmond (soprano), Jess Dandy (contralto), Anthony Gregory (tenor), Renato Dolcini (bass-baritone, Pilate), Alex Rosen (bass, Jesus). Les Arts Florissants / William Christie (harpsichord/director). Barbican Hall, 19.3.2019. (CC)

United Kingdom Bach, Johannes-Passion: Reinoud Van Mechelen (Evangelist), Rachel Redmond (soprano), Jess Dandy (contralto), Anthony Gregory (tenor), Renato Dolcini (bass-baritone, Pilate), Alex Rosen (bass, Jesus). Les Arts Florissants / William Christie (harpsichord/director). Barbican Hall, 19.3.2019. (CC)

Bach’s St. John Passion (Johannes-Passion) seems to ever take second place to the St Matthew Passion in terms of number of performances and recordings; a shame, as it is itself a masterwork, as William Christie and his forces reminded us. With an imbalance of halves, some 35 minutes initially against 70-odd in the second, it is really in the latter stages that we, the audience, can truly immerse ourselves in the work’s genius. First performed in 1724, and thus predating the St Matthew Passion by some three years, there are a significant number of revisions (1725, around 1730, 1732, 1749). The Bärenreiter Edition, which was used tonight, uses the final version as its basis.

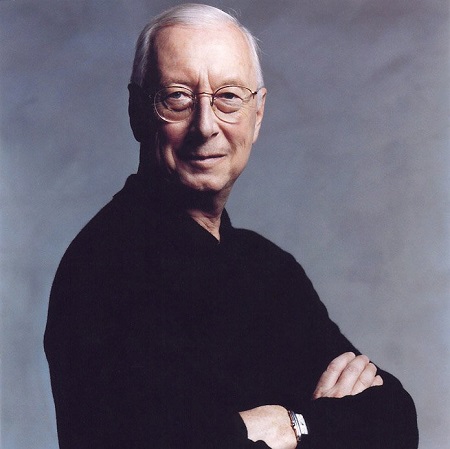

William Christie, with his group Les Arts Florissants (celebrating its 40th birthday this year) offered a reflective take bathed in much beauty. Christie used a two-manual harpsichord. The intimacy of the performance was reflected in the size of the choir: twelve-strong, bolstered by the soloists who took their place within the ranks for the choral sections. An orchestra of 16 (6 violins, two violas, two cellos) was joined by a continuo group of cello, viola da gamba, double-bass, lute and harpsichord/organ. It was lutenist Thomas Dunford of the latter group who stood out, his sense of chamber ensemble palpable, his ability to listen to his colleagues beyond doubt, his flourishes beautifully imaginative.

The work’s remarkable opening was underlined here by buzzing strings against dissonant, pungent winds, the chorus’s cries of ‘Herr’ carrying restrained but definite power; similarly, there was plenty of energy in the chorus’s later interjections of ‘Jesum von Nazaerth’ and similarly in ‘Wir haben keinen König’, the rhythms electric. The orchestra, in combination with the chorus, in fact provided some of the most striking, poignant moments of the evening in the form of the punctuating chorales, those delivered pure and almost vibrato-less from the choir. The first, ‘O grosse Lieb’ provided the model for instances to follow, the phrases lovingly sculpted by both instrumentalists and singers; for the late chorale, ‘In meines Herzens Grunde’, the chorus was heard unaccompanied, the paring away of instrumental sonority allowing for a sudden deepening of emotion in the light of Christ’s death, the decision to leave the chorus seated for this intensifying the impact.

This reading was blessed by one of the finest Evangelists, Reinaud Van Mechelen, whose diction was exemplary throughout; and when Bach writes a long melisma, Van Mechelen gave us a beautifully spun line. With an often-honeyed tone, this was an Evangelist of high vocal beauty; yet the Part II passage around Barabbas was delivered with great energy. The Jesus, Alex Rosen, was perhaps not quite as consistently alluring of voice.

Soprano Rachel Redmond impressed my colleague Mark Berry in the role of Susanna in Le nozze di Figaro for English Touring Opera a year ago; this March it was clearly her turn to impress at the Barbican, her voice beautifully pure. Her aria ‘Ich folge die gleichfalls’ was a model of its kind, the flute obbligato in perfect congruence. Along with Van Mechelen, Redmond provided the finest singing of the night.

It was a pity that Jess Dandy, the contralto, was initially far too quiet, easily swamped by the orchestra (her later ‘Es ist Vollbracht’ was far more successful); a similar fate, to some degree, was the lot of tenor Anthony Gregory. Bass-baritone Renato Dolcini as Pilate could perhaps have made more of his part – particularly the moment when he states he could find no case against Jesus could have held more import – but overall this was a solid assumption.

Despite some small caveats, this was a St John Passion which was far greater than the sum of its parts; not to mention a salutary reminder as to the power of Bach’s masterpiece. Christie’s gentle direction steered his forces trough Bach’s score with practised understatement.

Colin Clarke