United States Mahler: San Francisco Symphony / Michael Tilson Thomas (conductor), Davies Symphony Hall, San Francisco. 16.5.2019. (HS)

United States Mahler: San Francisco Symphony / Michael Tilson Thomas (conductor), Davies Symphony Hall, San Francisco. 16.5.2019. (HS)

Mahler — Symphony No.7 in E minor

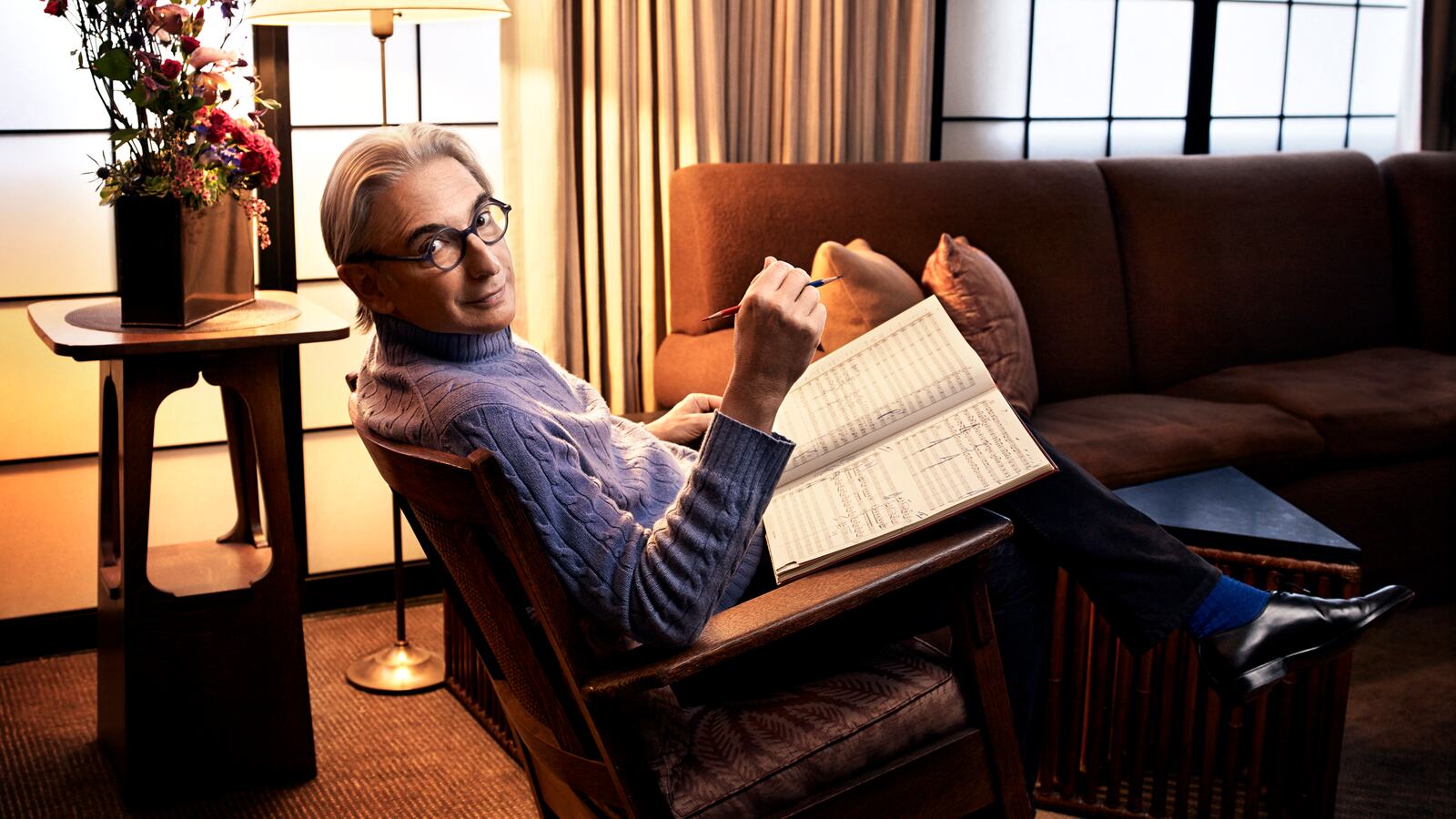

The Mahler partnership between the San Francisco Symphony musicians and music director Michael Tilson Thomas keeps bearing ripe fruit, even among the composer’s less-often-performed output. A complete CD set, completed in 2010, continues to be a benchmark compilation for this orchestra, and for this composer’s works.

Each season’s live versions of the Mahler symphonies remain something to anticipate with relish, as neither Tilson Thomas nor the orchestra seems satisfied to repeat the same interpretation. In the latest installment, the first of three readings of No.7 charged the atmosphere in Davies Symphony Hall.

Tilson Thomas’s approach to this rangy, messy score has been to let Mahler have his way, unapologetically bouncing from one extreme to another without any carefully placed transitions. This time the pacing never felt jarring, even as each turn of the page rounded a corner into a fresh landscape.

It was not a flawless traversal. The conductor looked a bit loosey-goosey on the podium, cracking quiet jokes with orchestra members between movements, perhaps needling them about some not-quite-tidy entrances here and there, or commenting on audience latecomers filing in after the first movement.

But overall, the ensemble gleamed with sassy brass, seasoned with let-it-all-hang-out percussion, and kaleidoscopic colors from the woodwinds. The finale wallowed in every wry swing the composer took in his pastiche of forebears such as Beethoven, Mozart and, especially, Wagner.

The opening movement, despite some less-than-neat entrances in quieter moments, started with principal trombone Timothy Higgins’s solo on Wagner tuba intoning the main theme, and a charming back-and-forth between the dueling French horns of principal Robert Ward and associate principal Bruce Roberts. There was also a certain charm in letting the score’s shifting moods run into blind alleys, then blithely pushing on to other ideas.

The central ‘night music’ suite yielded some appropriately spooky playing, especially in Nachtmusik I’s eerie march. The Scherzo that followed seemed less spectral than usual — a bit more up-front, concerned less with creating a ghostly atmosphere than with spelling out the disintegration from an off-kilter waltz to quiet chaos. In Nachtmusik II, concertmaster Alexander Barantschik’s solo sashayed in like a regal intruder before morphing into tender sweetness.

Timpanist Edward Stephen kicked off the boisterous finale with lapel-grabbing flourishes. Mahler’s unsettling parodies — of Beethoven’s Fifth bursting into C-major sunlight, and Wagner’s tone-poem marches in Die Meistersinger — heralded a bright new day. The trumpets’ fanfares flared brilliantly before deadpan detours into a trippy version of a chorale and other blind quotes from Die Meistersinger led to with a rousing reprise of the big tune from the first movement.

It would be easy for all this to spin off the rails, but this orchestra knows its way around the Seventh too well. It finished with all parts intact and received a well-deserved ovation.

Harvey Steiman