Switzerland Bellini: Norma: Soloists and Chorus of the Opernhaus Zürich, Philharmonia Zürich / Fabio Luisi (conductor), Opernhaus Zürich, Zurich, 2.6.2019. (CCr)

Switzerland Bellini: Norma: Soloists and Chorus of the Opernhaus Zürich, Philharmonia Zürich / Fabio Luisi (conductor), Opernhaus Zürich, Zurich, 2.6.2019. (CCr)

Production:

Director, Set designer, Lighting concept – Robert Wilson

Co-Director – Gudrun Hartmann

Costumes – Moidele Bickel

Lighting design – AJ Weissbard, Hans-Rudolf Kunz

Co-Set designer – Stephanie Engeln

Choir director – Ernst Raffelsberger

Dramaturgy – Konrad Kuhn

Cast:

Pollione – Michael Spyres

Oroveso – Ildo Song

Norma – Maria Agresta

Adalgisa – Anna Goryachova

Clotilde – Irène Friedli

Flavio – Thobela Ntshanyana

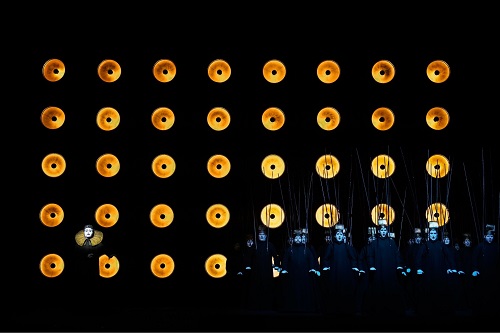

This is Robert Wilson’s Bellini. The set is the light. Light is the object. The shapes contain and direct the light, the shapes are the events. The events happen in the time of the music. The music is fixed, and the events are static. They are fixed points on a line. When the line has been brought to its end, you go home. The tragedy of the priestess Norma has been told.

There mightn’t be a ‘right’ way to watch this production of Norma, but there are a few wrong ones. Don’t expect the characters to display their story on the stage, they won’t enact it. Don’t expect an allegory, a 1:1 hook for what this means or what that means; any one symbol is so abstract it resists interpreting, asking you just to look at it instead. Don’t expect any clear epoch or visual idiom; there are beehive hairdo’s and antiquated futurism, and streetlamps that evoke drones, and an electronic igloo temple, and not a whole lot else. Above all: don’t expect intoxication. There are passages that will bring you fully in, and other passages will leave you cold. Brecht gave his viewers cigarettes to smoke during his plays so that they wouldn’t get too absorbed in their own emotions. For his part, Wilson might try passing out mescaline.

Uncustomary as it is, at no point during this at-several-points-tedious production did I find myself wishing for a more standard one. A traditional Norma would have its own challenges, its own tedium – very little actually happens in the story, there is remarkably little action to show, there’s one too many chance meetings in the forest, and the choir would mostly have to stand around anyway. One effect of Wilson’s work is that it reminds the frequent opera-goer of something he likely doesn’t care to admit: the plot of an opera, by itself, is often the least important aspect of all. It’s often propped up when the music works, and it’s often threadbare when the music doesn’t.

The extreme slowness of Wilson’s staging intensifies the music, though not always by way of hypnotism. Yes, there is such a thing as cosmic bel canto: just listen to the orchestral brooding that conductor Fabio Luisi gives us in the set-up to the great aria ‘Casta diva’, right as an ambiguous sphere begins to rise. For the record, Luisi’s conducting was on the whole martial, slower, with saturated bursts for a funeral pyre and gorgeously sombre details elsewhere. You hear these things even more freshly when there is so little to see. But not every inch of this garden is so enchanted. A gyroscope that appears prominently in Act II, maybe meant to illustrate some Riemannian idea of volatility, is so tacky and clunky that the music is the only thing worth your attention.

First and foremost, the staging intensifies the story. Making the stage abstract – showing little other than rectangles of light, or squares of ice – leads in turn to an abstractification of the human drama before us. Instead of having us think of Norma’s portrayal of her jealousy towards Adalgisa as being either convincing or unconvincing, the soprano (the excellent Maria Agresta) faces her audience squarely and seems, slate-faced, to present the concept of jealousy itself. Bellini and his librettist gave us plenty of societal questions to contend with, like whether religion is at odds with love, whether religious leaders make good political ones, whether prolonged peace can be fatal if it means placid repression, or even whether the Roman ancestors of 1830s Italy had in fact been the inferior culture to the Druids, so solemn and righteous they were. Good productions can tease these ideas out, or focus on more basic human concerns, like those of a troubled mother and her illegitimate children. Wilson bypasses all of this, and tragedy is reborn.

The problem is the movements. The singers don’t really walk, they slowly traipse. They don’t raise their arms, they lock them out. They don’t move their hands around, but jut them at angles and hold them there until some shift in the story or mood prompts a new gesture. And they certainly don’t sing to each other. The characters never once touch. Opera singers being opera singers and not, say, iemoto masters of Nō theatre, the effect isn’t always captivating; it’s just as often soporific.

The programme for this production is bold enough to cite Kleist’s Über das Marionettentheater, the great essay of aesthetic theory that asks whether a puppet can achieve a higher state of grace than a human actor, since human consciousness will always be aiming to achieve grace, while something without a will can be naturally graceful, divinely graceful. The answer, of course, is yes, but this Norma doesn’t treat the viewer to a stage of sublime puppets or an unblemished statue of the Boy with Thorn. With the movements, Wilson demands a tad too much of his performers, who at the end of the day are simply reasonably well-rehearsed good sports. (Wilson himself was on stage to take a bow for this second revival of his 2011 production, indicating that he had had at least a few days with the cast in order to convey to them his artistic intent.) Particularly when wearing some of the more spaced-out costumes by the late, great Moidele Bickel, they couldn’t help but betray a hint of how silly they felt.

Good sports all the same, and damn good singers. American tenor Michael Spyres, debuting as Pollione, had a roller coaster of a night, starting out too brash and sounding barky in his initial cavatina ‘Meco all’altar di Venere’, before soon settling into a lushly dark and emotive sound – though seemingly at the expense of any ring behind the top of his voice, which he appeared to be nursing. The young bass Ildo Song sounds better and better the more I hear him, appearing here as Norma’s father Oroveso, and like Spyres new to his role. After delivering a winning Alessio in La sonnambula last month, he’s a veritable Bellini specialist by now, given the stately but buoyant sound he maintained.

As Adalgisa, mezzo Anna Goryachova was the performer whose embrace of the movements most fulfilled Wilson’s vision, showing unforced remoteness as a means of theatrical power. Her tension as she moved was transfixing, and although tension is a singer’s kryptonite, Goryachova somehow found a high-voltage staticity that never interfered with her velvety sound and perfectly blended singing in the duets. Her duet counterpart and rival, Maria Agresta as Norma, was arresting in her own way; sneaking in a sighing bosom here or a lilted eyebrow there, she humanised the role despite herself, and in full concert with Bellini’s most masterful score. Despite a patch of too-slippery coloratura and some lost urgency in the text, Agresta summoned a dramatic soprano climax after achingly lyrical diminuendi in her ‘Casta diva’ appeal to the moon. The upshot: even in a revival, these singers succeeded musically and theatrically in showing all that’s compelling about a difficult production.

This revival of Norma runs for four more performances through June. For an interview with Robert Wilson about this production, click here.

Casey Creel