United States Adès, Adès & McGregor: A Dance Collaboration: Dancers of the Royal Ballet and Company Wayne McGregor (choreographer: Wayne McGregor), Los Angeles Philharmonic / Thomas Adès (conductor), Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, Los Angeles, 13.7.2019. (JRo)

United States Adès, Adès & McGregor: A Dance Collaboration: Dancers of the Royal Ballet and Company Wayne McGregor (choreographer: Wayne McGregor), Los Angeles Philharmonic / Thomas Adès (conductor), Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, Los Angeles, 13.7.2019. (JRo)

(c) Cheryl Mann

The Dante Project Part 1(Inferno)

Music – Thomas Adès

Design – Tacita Dean

Lighting – Lucy Carter and Simon Bennison

Dramaturgy – Uzma Hameed

Dancers – Artists of The Royal Ballet

Outlier

Director – Wayne McGregor

Music – Concentric Paths (Adès)

Violin – Leila Josefowicz

Sets – Wayne McGregor and Lucy Carter

Lighting – Lucy Carter, recreated by Simon Bennison

Costumes – Moritz Junge

Dancers – Company Wayne McGregor and The Royal Ballet

Living Archive: An AI Performance Experiment

Director – Wayne McGregor

Choreography – Wayne McGregor in collaboration with the dancers

Music – In Seven Days (Adès)

Piano – Kirill Gerstein

Video – Ben Cullen Williams

Lighting – Lucy Carter

Dancers – Company Wayne McGregor

In a triumphant collaboration, music, dance and art came together in Thomas Adès and Wayne McGregor’s Inferno to create that rarest of species, a perfectly realized contemporary ballet that takes its place in a line of classics beginning with the nineteenth century’s famed story ballets. The most apt comparison is to the Stravinsky-scored ballets of the Ballets Russes in the early twentieth century, such as Firebird, Petrouchka and Rite of Spring, where the visual, musical and choreographic language exist in perfect harmony to create complex yet accessible work.

Adès’s score for The Dante Project Part 1 (Inferno) is 45 minutes of pure excitement, evoking but never imitating Tchaikovsky, Stravinsky, Shostakovich and, by the composer’s own declaration, Liszt. The piece premiered at Disney Hall in Los Angeles in May with Gustavo Dudamel conducting the LA Philharmonic. Now set to dance and in its world premiere, the success of this piece as a ballet score is wildly apparent.

The twentieth century’s famous dance collaborations come to mind: Stravinsky and Balanchine, Bernstein and Robbins, Britten and Cranko, Cage and Cunningham, Glass and Childs, but it is hard to think of a full-length story ballet of the late-twentieth or twenty-first century where original music has been composed in collaboration with the choreographer. More often, choreographers turn to existing music to score their ballets, often with mixed results.

Adès’s score, the first part of a full-length ballet to be performed in London in 2020, brought out the best in McGregor and proved that although his career has favored modern dance movement over ballet, he is more than up to the task of creating a classically-based ballet. With the dancers of the Royal Ballet, McGregor has a dream cast of principals and soloists bringing their technical superiority, refinement and dramatic expressiveness to bear on his choreography.

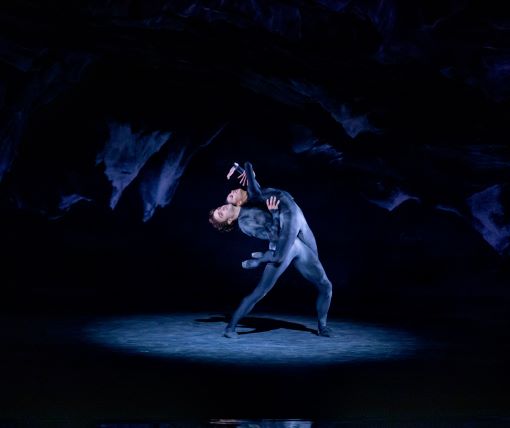

McGregor’s modern dances, which include movements such as undulating torsos, bent limbs and deeply arched backs, are often combined with the gestures of ballet. However, in Inferno there was a harmonious pairing of contemporary dance with the grandest of classical forms. The result was movement designed for the rigors of the inferno – tragic yet timeless without cliché or excess. Inferno felt like a concentrated flow of movement as Dante descends deeper and deeper through the circles of hell.

Tacita Dean created a chalky black and grey cavern as a backdrop for the dancers. Abstractly rendered yet illustrative of the underworld, it set the mood for a trip through Dante’s levels of hell. The costumes were inspired – pieces of performance art in themselves. Black unitards covered the dancers’ bodies from neck to ankle and were dusted with white chalk that drifted into the air as they danced. The lower the level of hell, the more chalk on the fabric of the character who resided there, conveying the notion that hell was growing colder and that some individuals were turning to ice or stone.

Though the sets were somber, the lighting moodily ominous and the dark drama of McGregor’s choreography apparent, there was the wit, charm and buoyancy of Adès’ music to place us firmly in the tradition of grand ballet. And McGregor answered the call by showing off his male dancers’ virtuosity in ‘The Thieves’ section, to a wild gallop scored in the tradition of Shostakovich.

Designed to follow thirteen levels of hell, with adulterers, gluttons, popes, critics, flatterers, hypocrites and thieves in attendance, the principals and soloists of the Royal Ballet delivered a tour de force of expressive dancing. Edward Watson as Dante, the dramatic center of the piece, danced a fervid pas de deux with a powerfully tragic Fumi Kaneko. In the second pas de deux, with strings reminiscent of Stravinsky’s Firebird, Francesca Hayward and Matthew Ball’s dancing had a lushly elegiac quality. Calvin Richardson’s solo was striking with its mix of primal movement and elegant classicism.

The evening began with McGregor’s Outlier, created in 2010 for the New York City Ballet and visually influenced by the abstract paintings of Josef Albers and Barnett Newman. The backdrop, designed by McGregor and Lucy Carter, consisted of concentric red circles, followed by tall rectangles in gradations of grey – beautiful in its purity. McGregor has a keen eye for design and an understanding of modern art. Set to Adès’ Concentric Paths with its unpredictable structure and jazz-inflected moments, it was danced by both Royal Ballet members and Company Wayne McGregor. Violinist Leila Josefowicz was in the pit with the LA Phil, superbly playing the complex score. Here were ballerinas on pointe and their partners juxtaposed with McGregor’s own performers, each bringing their own stamp to the movements, making for an engaging piece.

(c) Cheryl Mann

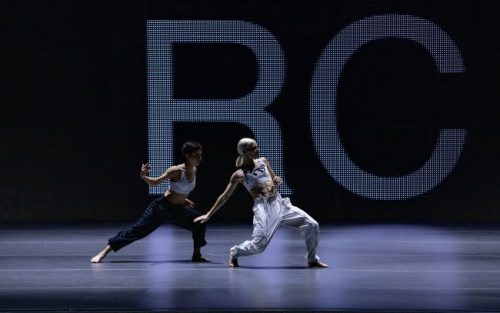

Following Outlier and aptly titled Living Archive: An AI Performance Experiment, this premiere may have been called an experiment but it was a fully staged dance in collaboration with Google’s Arts and Culture Lab. The Living Archive is described as ‘an artificially intelligent choreographic tool, trained on hundreds of hours of video from the choreographer’s extensive back catalogue, as well as solo material created on each of the current companies’. From this material, the system predicts movement and suggests movements to follow.

Set before a visually enticing background grid of projected computer codes and patterns, dancers from Company Wayne McGregor thrust their necks out in turtle fashion, undulated torsos, quivered like Jell-O and traced grand patterns with arms and legs. The process of creating the dance resonated with elements of Judson Dance Theater and 1960-70 Conceptual Art, when artists were trying to eliminate some of the arbitrary nature of producing images. Though McGregor’s ‘experiment’ was an intriguing premise and contributed to the process of artistic creation, it ultimately mattered little to the final product. Movement became unfocused, the screen distracted and patterns were indiscernible, except during the rare occasions when dancers moved in sync.

Adès’s exquisite In Seven Days with its jazzy chords, cascading melodies and fiery crescendos was terrifically played by the LA Philharmonic with Kirill Gerstein on the piano. As far as the evening went, so effective was Adès’s music as a springboard to dance that one hopes there will be more and more to feast ears and eyes on in the future.

Jane Rosenberg