United Kingdom Tim Benjamin’s The Fire of Olympus (or, On Sticking It To The Man): Soloists and Orchestra (harpsichord: Alex Robinson) of Radius Opera / Ellie Slorach (conductor). Burnley Mechanics, Manchester Road, Burnley, 14.9.2019 (RBa)

United Kingdom Tim Benjamin’s The Fire of Olympus (or, On Sticking It To The Man): Soloists and Orchestra (harpsichord: Alex Robinson) of Radius Opera / Ellie Slorach (conductor). Burnley Mechanics, Manchester Road, Burnley, 14.9.2019 (RBa)

Production:

Libretto – Anthony Peter and Tim Benjamin

Director – Tim Benjamin

Design – Lara Booth

Cast:

Pandora – Charlotte Hoather

Prometheus – Sophie Dicks

Epimetheus – Elspeth Marrow

Hephaestus – Michael Vincent Jones

Zeus – Robert Garland

The composer and all-round practical musician Tim Benjamin has quite a thing for opera – even though it is one of the most demanding forms artistically, financially and in terms of risk. His suffragette opera Emily (like The Fire of Olympus, designed by Lara Booth and with Anthony Peter’s collaboration on words) was reviewed here, as was his trumpet concerto. Benjamin, a pupil of Anthony Gilbert, Steve Martland and Robert Saxton, lives in Todmorden. In the early 1990s, he was BBC Young Musician of the Year.

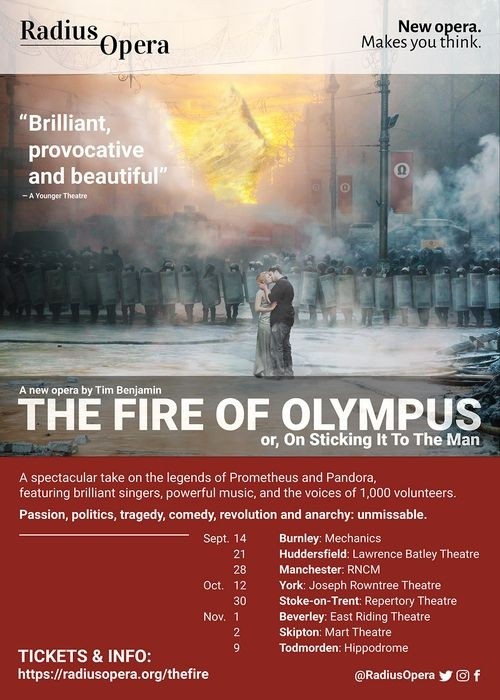

The Fire of Olympus – stuffily, I cannot bring myself to repeat the sub- or alternative title – is Benjamin’s eleventh opera since 1996. This was the work’s premiere and it is sung in English. Blanket performances of the opera ensure that the North of England can experience the work. Over the next two months there will be showings in Huddersfield, Manchester, York, Stoke-on-Trent and Mr Benjamin’s native Todmorden, West Yorkshire. He is one of town’s most prominent musicians. There also is a film of The Fire, to be premiered during the Leeds International Film Festival on 16 November 2019. Those curious about this work also have access to some Vimeo ‘shorts’: ‘One Thousand Voices’, ‘Legendary Characters’ and ‘Pandora’.

The opera re-engineers the Greek legends of Prometheus and Pandora. Benjamin had in fact given advance notice that he might tackle the theme. Very much against the time and tides of the day in 2016, he wrote an oratorio Herakles for five solo singers, narrator, choir and large orchestra. It ends with the narrator saying ‘Perhaps now I shall tell you the story of Prometheus … but no that can wait for another time’. That time came in the Lancashire town of Burnley, in the well-fitted-out theatre known as Burnley Mechanics next to the Borough’s Town Hall.

Attendance was meagre: perhaps 60 in a hall that can seat about 500. The weather was good, although this was the televised night of the Last Night of the Proms at the Royal Albert Hall. The work was fully staged and simply but strikingly costumed. The set which, lighting apart, remained identical from start to end, comprised various monoliths, a lectern and ceiling-high frames. A small pile of books, a globe and a double bulb bottle. The frames and lectern were decked out with drapes, each bearing a single O with an opening at the foot – like a broken omega – and presumably suggesting the realm of Olympus (the mise-en-scène) and redolent of some fascist symbol. The whole effect conjured up a Nuremberg rally with Leni Riefenstahl and Josef Goebbels in the wings. Zeus naturally heightens the effect when he speaks from the lectern. At one point in Act II, he struts and mugs the audience like Mussolini.

The whole work, a full two-and-a-half hours including intermission, is laid out in a prologue, two acts and an epilogue. The epilogue has a warning to the future, although I am not sure we need such warnings. The music is memorable but then so are the central characters. Zeus is a ‘bad lot’, vengeful, self-serving. He rewards loyalty with humiliation and worse; he is cynical and endowed with demagogic, highly polished manipulative crowd-pleasing skills. I have to say that one of several highlights is his exultant aria from the lectern ‘Times of plenty, times of mirth’. Zeus forms a triptych with two superbly portrayed minions: Pandora and Hephaestus, both Aryan blondes to the hair roots. Pandora (a very impressive Charlotte Hoather), clad in statuesque white, is Zeus’s much put upon ‘chef du cabinet’: he rips up her proposals for speeches page by page and flings them to the floor as the despairing Epimetheus does to ripped out book pages later on. Zeus tries to use her as an object sexually to achieve his own ends as a ‘honey-trap’ for Epimetheus. For me, one of the stars was Michael Vincent Jones as the loathsome Hephaestus. He played this, as intended, as caricature with Nazi-style double-breasted trench coat, supernatural whip, dark glasses, oiled-back hair, a limp and, perilous touch this, a crooked walking stick – the latter kicked away several times by Zeus. His facial expressions ranged from fawning to fury to simper, to leering sadism. He is an eerie and chilling presence drawing on aspects of Heydrich, Spoletta and (to use a contemporary fictional image) George Warleggan. Strangely, the self-searching and self-analysing ‘heroes’ who bring Olympus down, Prometheus and Epimetheus register less strongly. Their singing voices, however, were superb. They have much that is touching to communicate, and they achieve that end immaculately.

The excellent conductor of a fine orchestra of eleven, including harpsichord, oboe and strings, was Ellie Slorach. (She may be a relative of the Scots soprano Marie Slorach who used to appear on BBC Radio 3 in the 1970s.) The musicians were arranged in a custom-made ‘pit’ in front of the raised stage. The populace of Olympus are represented by tumultuous and thunderous crowd noises assembled digitally from one thousand singers recorded in ‘workshops’ across the North of England.

The musical style is recognisably Handelian (and Vivaldian) but with some most touching and inventive refinements: the patina of Sibelius’s Valse Triste and the instrumental parts of Warlock’s The Curlew jumped out at me. The music is not pastiche. In addition to the allusive nuances already mentioned, it was often telling and moving. Examples are two ‘arioso’ episodes where the oboe sings a song worthy of Keats’s ‘senseless trancèd thing’ accompanying the singing of characters central to that scene. There are many poignant moments. I will mention a ‘Queen of the Night’ moment for Pandora. It will always be a risk with this opera that Pandora and Hephaestus might rather shade the other characters; there are after all only five of them. It is a work that I would like to hear again.

Rob Barnett

For more about Radius Opera click here.