United Kingdom Oxford Lieder Festival 2019 [5] – various composers: Carolyn Sampson (soprano) Joseph Middleton (piano), and others. Oxford various venues, 12 to 26.10.2019. (RD)

United Kingdom Oxford Lieder Festival 2019 [5] – various composers: Carolyn Sampson (soprano) Joseph Middleton (piano), and others. Oxford various venues, 12 to 26.10.2019. (RD)

Carl Loewe: Lieder and lectures devoted to German Ballad and Lieder composer

Debussy – Les Chansons de Bilitis; Six Épigraphes Antiques

Stravinsky – The Rite of Spring (arranged by the composer for piano duet)

Haydn – Arianna a Naxos Hob XXVIb/2: solo cantata for soprano and piano

Schoenberg – Four Lieder Op.2

Mahler – ‘Das himmlische Leben’ and ‘Das irdische Leben’ from Des Knaben Wunderhorn

Koechlin – ‘Hymne à Astarté’ Op.39; Épitaphe de Bilitis Op.39

Richard Strauss: Four Last Songs Op.Posth: ‘Frühling’; ‘September’; ‘Beim Schlafengehen’; ‘Im Abendrot’

I attended the very first Oxford Lieder Festival, in 2002. It was a modest affair, centred on the Holywell Music Room, famous in Handel’s day for its acoustic, especially for chamber music and song recitals. Schubert figured, of course, and Schumann. But what impressed immediately was the youthful Sholto Kynoch, a former Oxford organ scholar, who devised and accompanied the recitals, and struck me as an articulate, intelligent, perceptive keyboard player; and at age 23 an organiser of obvious ability and flair.

(c) Robert Piwko

We have reached the 18th OLF, a far more extended series nowadays (two weeks in late October), spanning numerous venues and well-chosen, wide-ranging repertoire

The first single composer recital (another of Clara Schumann followed next day) formed part of a day devoted entirely to Carl Loewe (1796-1869), the 19th century Lieder composer, born in the old East Germany, and a match (many have alleged) for Schubert: ‘The Schubert of north Germany’, as some put it.

Loewe has been recorded – fabulously – by Brigitte Fassbaender, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and others. Here, ‘The Master Storyteller’, so called because of the narrative, ballad nature of many of his songs, featured in talks by Richard Stokes, Professor of Lieder at the Royal Academy of Music, and Schumann and his contemporaries expert Laura Tunbridge, Professor of Music at Oxford University.

That morning, Christina Gansch (soprano) and baritone Martin Hässler were accompanied, as always with great subtlety and sensitivity, by Sholto Kynoch (who also appeared with his Phoenix Piano Trio in Beethoven’s ‘Ghost’ Trio – which harnessed perfectly with this 2019 Festival’s main theme). The songs’ revelation was obvious: every ballad bespoke, if not genius, nearly so. Loewe is a major, still under-appreciated composer: a musical giant, in fact.

One full day’s programme I just could not miss: three concerts featuring French music (Debussy, Koechlin), included in a stunning programme at St John the Evangelist church – which offers its own enterprising year-long concert series – by soprano Carolyn Sampson, with accompanist Joseph Middleton. It included some lush, middle-period, tonal Schoenberg Lieder, Strauss’s Four Last Songs, and more.

The fortnight was entitled ‘Magic, Myth and Mortals’, with individual concerts dubbed ‘Fauns and Dryads’, ‘Elves and Sprites’, etc. Sampson opened with Haydn’s staggeringly dramatic monologue Arianna a Naxos, an extended (18-20 minutes) lament by the abandoned maiden, embracing despairing, shifting moods, despondent and suicidal. Sampson exuded acute pathos. For the emotion, compare Purcell’s enraptured solo ‘The Blessed Virgin’s Expostulation’, or several striking monologues from Greek Mythology by Bohemian composer Jirí Benda (1722-95): Ariadne, Medea and Pygmalion.

How often does one encounter concerts, let alone a same-day sequence, featuring Debussy’s ‘Musique de scène’, Les chansons de bilitis (twelve songs spanning 1894 and 1900 – when he worked on Pelléas) and the exquisite Six Épigraphes Antiques – instrumental treatments of six related Bilitis poems (Debussy preferred, French style, lower case ‘b’).

With these bewitching Épigraphes – in Debussy’s original four-handed piano version (1914) – Katya Apekisheva and Charles Owen unveiled 12 items of a unique delicacy. Such subtle, diaphanous music suggested Satie (and Ravel). There followed a spectacular, suitably angry, four-handed reading (arr. Composer, 1913) of Stravinsky’s ‘myth’ The Rite of Spring; the playing so lucid, one could one sense the ‘Lithuanian folksong’ Stravinsky later confessed lurked beneath.

Les Chansons de Bilitis (six fragile pieces for small ensemble), Op.7 was served up beguilingly by sensitive performers (several were current Oxford students): prominent paired flutes (Lucy Evans, Sarah Mattinson); harps (Gabriela Dall’Olio, Hero Douglas); plus – magically – celesta (Bethy Reeves). The beautifully observant speaker was French lecturer Helen Abbott. Bilitis includes enticing advance hints of Syrinx (1913), just as the Épigraphes echo it. Both works emulate Debussy’s sensitive chansons for his wife, the high-voiced soprano Emma Bardac.

The Épigraphes Antiques summon the goat-god Pan, with shy patternings, becoming quite randy and declamatory. That Debussian landmark, the whole-tone scale, featured prominently. A dark, heaving bass, haunting yet acquiescent (No.2), envisioned a sad ‘nameless’ grave. A rocking octaves ostinato, for the ‘propitious night’ (No.3), then skittered besottedly in upper parts. No.4, the ‘crotales’ (ancient castanets), anticipates Szymanowski, whose instrumental work titles are riddled with classical references. Then with astonishing skill, Debussy depicts the pluie of the sixth and last: a welcoming, not unpleasant, morning downpour.

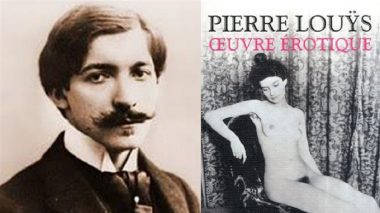

The Bilitis songs are sexy, absorbing, yearning. Why ‘sexy’? The source is the (Belgian-born) French poet Pierre Louÿs (1870-1925), who strove in his poetry ‘to express pagan sensuality’. ‘Bucolic’ (like the Sicilian poet Theocritus), ‘elegiac’, ‘sensual’, erotic’, ‘pseudo archaic’ are descriptions often suggested. Louÿs’ (143) poems allude to the imaginary girl/courtesan Bilitis, who sojourns in Pamphylia (modern Turkey), Cyprus and Mytilene.

Louÿs’ Lesbian themes of passionate longing (some so graphic as to be originally suppressed) owe much to fragments of the girl-adoring poetess Sappho. By the 1930s Louÿs was still exploring female sensuality. These Debussy settings, ‘gracieuse, ingénieusement archaïque’, were begun in 1894 (some claim 1897-8). A friend of Louÿs (as was the openly homosexual André Gide), Debussy must have pounced on the surprisingly titillating subject matter, making a personal selection. Certain of Louÿs’ extensive collections were published only after his death. The Greek-founded ones also inspired, a sensual coming-of-age film, Bilitis (1977).

Sampson included Debussy’s setting of three Louÿs chansons, ‘La flûte de Pan’, ‘La chevelure’ and ‘Le tombeau des Naiades’; two Lieder from Mahler’s ‘Des Knaben Wunderhorn’ (1888-9), one jolly, one tragic; and to finish, Strauss’s searing swansong, Vier letzte Lieder (Four Last Songs) (1948). Middleton greatly impressed: his pauses, calculated lacunae and discreet, nuanced piano entr’actes seemed endlessly inspired. ‘Im Abendrot’ was placed last: taken too slowly, hyper-emotional yet evincing the very opposite: a gooey effect. So too the equally sentimentally rendered Strauss encore. Slushy, both bad mistakes in such a previously superlative recital.

The sensation was Charles Koechlin’s (1867-1950) two settings, textually related to the Debussy: ‘Hymne à Astarté’ Op.39, was sensational: clattering, boisterous, explosive, and invoking, fascinatingly, elements of Koechlin’s distinctive, non-imitative individualistic style: bitonality, atonality, relatively complex polyphony, and so on. Astarte (Ishtar) was ‘The Queen of Heaven’ or ‘primordial goddess’ to antiquity. Koechlin’s ‘Épitaphe de Bilitis’ was the reverse: pianissimo, with grieving falling patterns and touching, resigned final words: ‘The memory of my terrestrial life [shall be] the delight of my subterranean.’

The start to the whole Festival, which began with Norse Gods and Beowulf, was just as glorious. The first evening concert, at Oxford’s Town Hall, was orchestral: the BBC National Orchestra of Wales (BBCNOW) under the gigantic figure – and personality – of the orchestra’s ex-music director, Dutch conductor Jac van Steen. The pairing of here of Schubert and Grieg gained relevance from the former’s music for Rosamunde (disguised as Cyprian shepherdess, exiled, then restored as queen) in Brahms’s version; a daring orchestration of ‘Der Erlkönig’ by Berlioz; and the song ‘Prometheus’ D674 (later ravishingly orchestrated by Max Reger, D 674).

But the plum was swathes of music from Grieg’s Peer Gynt music – not just the Suites Op.46 and Op.55). Grieg had composed much ampler Peer Gynt music (Op.23) in 1874-5 for fellow-Norwegian Henrik Ibsen’s five-act play. The programme, ill-judgedly, emphasised the ‘hair-raising’ item ‘In the Hall of the Mountain King’, and the ‘haunting’ number ‘Solveig’s Song’. Jac van Steen would have none of this. He proved, in a way he so distinctively articulates (think of Carlos Kleiber), that less familiar passages of Grieg’s complete 26-movement Peer Gynt music were phenomenal – and, one suspects, influential on younger composers. Camilla Tilling and Neal Davies were imaginative and compelling soloists. Van Steen drew from the Welsh orchestra marvellous precision, a finely instilled sense of style, intensity, dynamic, and rubato. So the 2019 festival launched out triumphantly, and this spirit endured throughout.

The usual concentration on Schubert (see Curtis Rogers’s review below of Roderic Williams) was extended further, to marvellous effect, by baritone Marcus Farnsworth, who having rounded off his own enlightened creation, the Southwell Music Festival, Nottinghamshire (in mid-August), and poised this November to sing the role of Ned Keene in Britten’s Peter Grimes at Bergen, treated this Oxford audience, jointly with soprano Katherine Broderick, to a stimulating and warming selection of Hugo Wolf’s 50-plus Mörike Lieder (1888).

Concluding this triumphant 18th Oxford Lieder Festival, lyric soprano Louise Alder (who made her name at the 2017 Cardiff Singer of the World Competition) joined Belarussian opera star Nikolay Borchev in a concert reverting to Schubert, Schumann, and Liszt, with Sholto Kynoch accompanying. Liszt’s underperformed Lieder, such as ‘Gretchen am Spinnrade’, ‘Die drei Zigeuner’ or ‘Über allen Gipfeln ist Ruh’ (Liszt the virtuoso also made piano transcriptions of sundry Schubert songs), invariably prove masterpieces, indeed was proved here with their ‘Die Lorelei’ at St. John The Evangelist.

With Graham Johnson, James Gilchrist, Christoph Prégardien and Jacques Imbrailo plus numerous others engaged, it is hardly surprising the Oxford Lieder Festival has achieved its international reputation – for excellence, imagination and inspiration. It is here to stay. Marvellous news.

Roderic Dunnett

Having attended many of his concerts with the BBC National Orchestra of Wales, I too am a fan of Jac van Steen. However, he was never the orchestra’s music director as stated in this review. He used to be their principal guest conductor.