United Kingdom Britten, Death in Venice: Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal Opera House / Richard Farnes (conductor). Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London, 21.11.2019. (JPr)

United Kingdom Britten, Death in Venice: Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal Opera House / Richard Farnes (conductor). Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London, 21.11.2019. (JPr)

Production:

Libretto – Myfanwy Piper

Director – Sir David McVicar

Designer – Vicki Mortimer

Lighting designer – Paule Constable

Choreographer – Lynne Page

Cast included:

Gustav von Aschenbach – Mark Padmore

Traveller / Elderly Fop / Old Gondolier / Hotel Manager / Hotel Barber / Leader of the Players / Voice of Dionysus – Gerald Finley

Tadzio – Leo Dixon

Apollo – Tim Mead

Lady of the Pearls – Elizabeth McGorian

Jaschiu – Olly Bell

In a particularly informative programme for Death in Venice Felicity Rosslyn, a family therapist, reminds us how ‘Britten’s choice of subject is supersensitive in our age of vigilance towards sexual safety and the universal condemnation of paedophilia. But as Ian Bostridge phrased it when preparing himself for the role of Aschenbach, “this seems a weird judgement on a work in which a writer who admires a beautiful boy from afar on a Venetian beach is condemned to die of cholera.’ Towards the end of his life his 1973 Death in Venice is clearly an autobiographical work for Britten, in a similar way as the late symphonies are for Mahler who was the inspiration for Thomas Mann’s original novella and someone Britten greatly admired. For Mahler it was the death of a child, dodgy heart, and a wayward wife – amongst much else – that suffused his music whilst Britten’s Death in Venice could not be a clearer statement of aspects of his sexuality, whether repressed or otherwise. Those more knowledgeable than I am suggest that the composer did have a fascination for adolescent boys, so perhaps in 2019 a new production should be more psychoanalytical; and certainly if you swop ‘AIDS’ for ‘cholera’ it would put an entirely different slant on the work.

I will admit this was my first Death in Venice and will likely prove the only performance of it I will ever see. There were several powerful moments, most notably the ending, but its longueurs are clear for all to see and hear and undoubtably might have been addressed had Britten not been in declining health during and after its premiere. I began to wonder about a Matthew Bourne reimagining of Death in Venice as a complete ballet to Britten’s music beginning in New York’s gay bathhouse culture of last century and ending in an AIDS clinic.

Given that Sir David McVicar’s brief was not to bring any new insights into the work, he stages the ageing man’s homoerotic infatuation with a young boy quite straightforwardly. The director and his designer, Vicki Mortimer, reject a naturalistic depiction of Venice for an impressionistic approach. No boundaries are crossed, and our attention can simply focus on Tadzio who is stalked by Aschenbach, who himself, is stalked by multiple characters all representing death. Apart from when the stage opens up for a view of a shimmering blue sea, McVicar’s Venice is gloomy and oppressive showing us disease as a miasma haunting the city; although he does capture the opera’s Edwardian world of leisured classes – in their grand Venetian hotel – rather well. There was also a magnificent full-sized black gondola, an image which resonated with me because it must have been very much like the one that transported Richard Wagner’s body through Venice after he died there in 1883.

Therefore, McVicar’s job was mainly to keep the two main protagonists apart and just chart someone’s self-destruction through delusions of intimacy with the object of his admiration who he never even approaches. Tadzio is portrayed by a (silent) dancer who therefore inhabits a different world to Aschenbach and so Britten ensures there can be no possible connection between the two of them. Helping to ‘sanitise’ the work somewhat Tadzio is a young man whose muscular physique was far from childlike, and also his playmates on the beach were similarly cast and their games translated from the schoolboy antics – that I suspect Britten envisaged – into something more macho and sporty. McVicar reinforces the sense of separateness by moveable columns that go back and forth across the stage repeatedly dividing man from ‘boy’.

Lynne Page’s choreography was – where necessary – elegant or appropriately rumbustious. Tadzio was the talented Leo Dixon (First Artist of The Royal Ballet) who moved well throughout the opera and – when given the chance to show off – produced some mightily impressive solo moments. McVicar ensured there was no unnecessary come-hither inducement and this Tadzio only noticed being noticed. If anything, it was all a game for him, and he was obviously someone capable – and old enough – to look after himself.

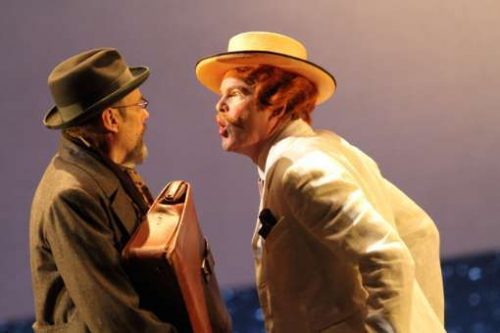

Accepting this scenario Aschenbach therefore needs to be more tragic than pitiable as he is brought low by his hidden desires. Mark Padmore is a recitalist and concert singer of world renown but, as such, is not always required to bring a great deal of expression or colour to what he is singing. Only in his closing scenes did Padmore’s descent really register. He seemed to relax at last and warmth – conspicuously absent at the start – began to course through his voice and his Aschenbach became immensely moving. His performance was in the shadow of Gerald Finley’s impressive virtuosity in seven baritone roles that are pivotal in Aschenbach’s downfall. Each vignette — including a mysterious Traveller, Elderly Fop, unctuous Hotel Manager, prattling Hotel Barber or bawdy Leader of some strolling players — was portrayed with such nuance and different vocal tone that is almost impossible to believe it was the same singer lurking beneath the different disguises. At times my mind wandered as to what Finley’s Aschenbach would be like as he is clearly capable – with his high baritone – of that role too.

This new production of Death in Venice was a wonderful ensemble performance from all the singers, dancers, and actors involved. Standing out from this throng was the unearthly beauty of Tim Mead’s singing as Apollo who Aschenbach envisions presiding over Olympian games at the Lido. All the singers do very well considering how little support they get for their vocal lines from Britten’s gamelan-infused exoticism. His music has a distinctively rich and diverse palette with prominence given to an eclectic variety of percussion. It took a while for Richard Farnes and his committed musicians to sound as if they had mastered Britten’s score: Act I lacked energy – possibly more Britten’s fault than Farnes’s – though the unsettling nature of the schizophrenic orchestration, for which this work is celebrated, imposed a relentless grip after the interval as the anguished denouement approached.

Jim Pritchard

For more about what is on at the Royal Opera House click here.