Germany Bayreuth Festival 2021 – Wagner, Der fliegende Holländer: Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of the Bayreuth Festival / Oksana Lyniv (conductor). 25.7.2021 performance and streamed (directed by Andy Sommer) for a limited time on DG Stage. (JPr)

Germany Bayreuth Festival 2021 – Wagner, Der fliegende Holländer: Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of the Bayreuth Festival / Oksana Lyniv (conductor). 25.7.2021 performance and streamed (directed by Andy Sommer) for a limited time on DG Stage. (JPr)

Production:

Director and Stage design – Dmitri Tcherniakov

Costumes – Elena Zaytseva

Lighting – Gleb Filshtinsky

Dramaturgy – Tatiana Werestchagina

Cast:

The Dutchman – John Lundgren

Senta – Asmik Grigorian

Daland – Georg Zeppenfeld

Erik – Eric Cutler

Mary – Marina Prudenskaya

The Steersman – Attilio Glaser

The same director and design team that recently gave us a new Der Freischütz in Munich (review click here) are now responsible for the new Der fliegende Holländer (The Flying Dutchman) which brought opera back to the Festspielhaus on Bayreuth’s Grünen Hügel after last season was cancelled at the height of the current pandemic. I have only missed a handful of summers there in well over two decades but now another two years have gone by without my annual R&R and who knows if I will ever go back again. Even before all the Covid precautions that are now in place going to performances there has recently not been as enjoyable an experience as it once was.

Beginning in 2016 because of the controversy about that year’s new Parsifal, as well as several terrorist atrocities in Germany and elsewhere, security around the Festspielhaus was heightened considerably. This meant those visitors being bused in from various hostelries in the town and surrounding villages having to yomp through a surprisingly disorganised car park before getting anywhere. This always reminded me why Wagner built his opera house there in the first place: it was far enough away from Munich and only those most devoted and dedicated to his music would undertake the journey in the ensuing 145 years. It’s the wrong language – but not for many of the visitors there that year, then subsequently, and now in 2021 – plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose!

Obviously, I saw the recording when available on DG Stage but reports suggest that if those previous precautions weren’t strict enough this has been ramped by to the nth degree. This summer apparently there is also a registration centre, test centre, mobile toilets and one-way systems. The reduced audience of 911 are given armbands(!) to show they are the chosen ones cleared of Covid to be there and masks must be worn throughout the performance. (How much of this Angela Merkel – making her last first night visit to the Bayreuth Festival as Germany’s Chancellor – had to go through is anyone’s guess?)

At last, a woman gets to conduct an opera at Bayreuth, not Simone Young who has always been oddly overlooked, but the young Ukrainian Oksana Lyniv and – though I was not in the Festspielhaus – she sounded to have done a fine job of it, although I felt I heard a little looseness with the stage and pit ensemble from time to time. This might only have sounded like this because the famed Bayreuth chorus was not all present onstage but half singing from elsewhere and being piped in with numbers on stage boosted, I have read, by lip-synching extras.

So, what do we see in Dmitri Tcherniakov’s Holländer: well, once again – as is the modern way – it is Tcherniakov’s version of the story we see and it is Wagner’s we hear. Everyone is singing about stormy seas, reaching safe harbour and a ghost ship but that is not the story we watch unfold. As is increasingly the norm, the overture cannot be left alone merely as a scene setter but there are a number of vignettes that introduce us to a stylised, plain and monochrome looking small town (with no sign of the sea). The projected German suggests what we are seeing is ‘The strange, recurring dream of H.’: ‘H.’ as in the Holländer (Dutchman). We see him as a young boy who catches his (unmarried?) mother having an affair with a married man (who is actually the young Daland). She is rather clingy, and he violently breaks things off with her. Gossip spreads amongst the townspeople (in Elena Zaytseva’s modern, yet timeless costumes) who introduce themselves by doing a conga and the boy’s mother is shunned, threatened and becomes an outcast, so much so that [spoiler alert] she hangs herself as he is left sadly grasping onto her dangling foot. And that’s just the overture!

We then read how ‘H. returns to his hometown after many years’. He sits glowering at a local bar (with ‘Kein WiFi!!’) and is a hulking, shaven-headed, granitic presence as the Steersman sings his song and his reminiscences are met by laughter from the patrons. There H. meets Daland (the man who ruined his mother’s life), not a sea captain but clearly – with his elegant overcoat and fedora – now a successful businessman. The stranger buys everyone a round of drinks and increasingly possessed by his memories begins to tell his story (‘Die First ist um’) to those only half-listening and who think he’s a little mad. The Dutchman learns of Daland’s unmarried daughter Senta and I suspect he has plans to ruin her life.

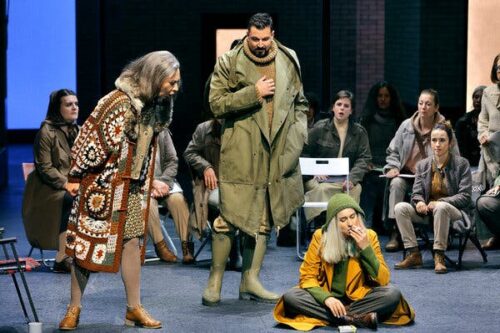

The buildings move silently around and create a town square for the local women’s choir who sitting on their picnic chairs are rehearsing the ‘Spinning Chorus’, led by Mary, who we discover is Senta’s mother. She drinks from a mug that I suspect we are to think has alcohol in it. We meet the rebellious Senta, a punkish troubled young woman with red and blue streaks in her bleached hair. The women find the line ‘Do you want to dream your whole life in front of the portrait?’ hilarious before she regales them with her ballad about the legend of the Dutchman. Oddly the photo passed around by the women doesn’t look at all like H. and is more like her lovelorn – but quick to anger – boyfriend Erik who tries to shake some sense into Senta during their confrontation. (There are a surprising number of cigarettes supposedly lit in this Tcherniakov’s staging and at one point Senta sits cross-legged trying to blow smoke rings.)

While Senta leans on a lamppost Mary lays a table in Daland’s dining room and there is the best china including a soups tureen, crystal glasses, candlesticks, bottles of wine and flowers. The dinner that ensues is very awkward with Senta and the Dutchman at opposite ends with her parents in the middle. She seems captivated by his tales (or maybe it’s his cable knit sweater she falls in love with?) and perhaps sees him as an opportunity to escape her stifling homelife. Mary is clearly conflicted and I wondered if we are to understand she recognises who H. actually is but is reluctant to confide in her husband.

For the concluding festivities we are at the edge of the town and the men and women are sitting at tables having some food and drink. Slightly to the side at the front are two other tables with men sitting around dressed soberly in blue and not joining in the general merriment which involves another riotous conga line. This is H. and his henchmen, though Tcherniakov lacks the conviction to overtly make them members of a secret-police organisation or even more credibly a neo-Nazi group led by the Dutchman. They are a silent threatening presence with the familiar utterances of the ghostly crew sung offstage and are there to help the Dutchman get his revenge on the town. Fights quickly break out and the Dutchman shoots a random bystander, though I was left wondering why that wasn’t Daland? Erik challenges Senta about her broken promises to him and the ending definitely needs reworking before the production returns next summer. Suffice to add that the Dutchman throws Senta to the floor just as her father had done to his mother. For whatever reason Mary enters with a double-barrelled shotgun, despatches H. causing Senta to laugh hysterically before she cradles the shaking Mary. Wagner’s redemption through love is only in his music as we see that the men who were there with H. have set the town alight and there are flames, billowing smoke, and falling ash as the opera ends with Senta slumped in a chair.

Lyniv and her wonderful Bayreuth orchestra created some vivid soundscapes in an account of the score that was never allowed to become becalmed while she emphasised the turbulence and bleakness of the music’s examination of the Dutchman’s tortured soul. In the title role John Lundgren was the perfect physical embodiment of Tcherniakov’s tortured and mentally challenged H. struggling to defy the hand fate dealt him and intimidating all he becomes involved with. However vocally it was a very mannered, rough and ready performance and Lundgren sounded under pressure more often than I would have expected. Georg Zeppenfeld is one of the great Wagner basses of all time and his flexible and resonant Daland didn’t disappoint but – given his character’s backstory that Tcherniakov shows us – surely he was much too genial and too full of bonhomie. Strangely the director doesn’t know what to do with Erik and I’m not sure Wagner did either: Eric Cutler’s putative love rival to the Dutchman is supposedly a huntsman and he still looks a bit like one. Having heard so many famous names mangle this relatively short role in the past it was a pleasure to hear Erik’s two set-pieces sounding effortless, lyrical and resoundingly passionate. Marina Prudenskaya’s Mary initially doesn’t look the most caring of mothers to Senta, though later plays the dutiful housewife in a scene where Wagner never intended her: Prudenskaya sings well as one of this opera’s other thankless characters. Another is the Steersman and Attilio Glaser sings tenderly of his sweetheart surrounded by his carousing mates at the bar.

Last but obviously not least, Asmik Grigorian gives one of the finest opera performances I have ever seen and does not just sing Senta, she becomes her! Grigorian’s dramatic conviction is total and her almost hyperactive gesticulations could be annoying if she wasn’t creating such a complex, living, breathing person, with a volcanic personality and eager to grab all life has to offer if she could only get the chance. Grigorian was a wonderful Chrysothemis in a recent Salzburg Elektra (review click here) and confirms with her Senta that she is one of the leading singing actors of her generation.

Jim Pritchard

Yes, excellent review in all points. Let me add two points.

If I would have been sitting in the Festspielhaus, I would have laughed out loud, as I did at home in front of my TV, when Zeppenfeld put on the exact same hat, that he had already wore as Marke…

And the basic flaw is of course, that no punk, with red and blue hair, would sacrifice her life for the prototype of an ‘old, white man’.

May I add that I found the ‘Don Giovanni’ in Salzburg only a few days later, to be a much better, almost brilliant performance?