![]()

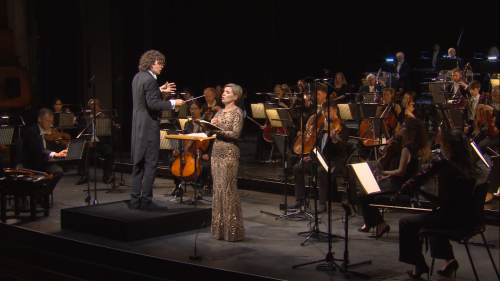

United Kingdom Vaughan Williams, Mahler – London Philharmonic Orchestra’s Rites of Passage: Sally Matthews (soprano), London Philharmonic Orchestra / Robin Ticciati (conductor). Filmed 15.6.2021 in the Glyndebourne Opera House (by Maestro Broadcasting and directed by Dominic Best) and available on Marquee TV from 2.7.2021. (JPr)

United Kingdom Vaughan Williams, Mahler – London Philharmonic Orchestra’s Rites of Passage: Sally Matthews (soprano), London Philharmonic Orchestra / Robin Ticciati (conductor). Filmed 15.6.2021 in the Glyndebourne Opera House (by Maestro Broadcasting and directed by Dominic Best) and available on Marquee TV from 2.7.2021. (JPr)

Vaughan Williams – Fantasia on a theme by Thomas Tallis

Mahler – Symphony No.4 in G major

I think only the idyllic South Downs surroundings (especially if the weather behaved itself) and the relatively new experience of hearing a Mahler symphony after all the shutdowns could have attracted a small, masked, and socially distanced gathering to the Glyndebourne Opera House for an orchestral concert rather than an opera. Arriving a couple of weeks later in an abridged version on Marquee TV we did not hear Purcell’s Music for the Funeral of Queen Mary and Birtwistle’s Cortege that they did, which with the Vaughan Williams made up a short first half before the traditional 90-minute dining interval. Given that the Mahler is – debatably – his shortest symphony then this concert possibly had equal music and equal interval.

As it is, this Rites of Passage London Philharmonic Orchestra concert is now barely 80 minutes on Marquee TV, though I am sure – like me – others watching would have appreciated the whole concert. The same Purcell, Birtwistle and Vaughan Williams works were performed by Ticciati with the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin last year (review click here).

Glyndebourne’s music director Robin Ticciati extolled his appreciation of Ralph Vaughan Williams’s Fantasia on a theme by Thomas Tallis by describing its ‘beautiful, lush, cathedral-like soundworld’ going on to say how the composer ‘goes back, as almost a collector going back to old melodies of Tallis, counterpoint, fugal writing. And at the same time combines it with the red blood of the turn of the century and [as] a pacifist and a composer that’s fighting for a united Europe. And this piece is a beautiful blend of both of those soundworlds, something raw, and at the same time, something open and transcendent.’

From this I assume that Vaughan Williams’s work for string orchestra – when it was first performed in 1910 – was his response to imminent war in Europe. Mentioning ‘soundworlds’ it clearly influenced Richard Strauss’s 1945 Metamorphosen for 23 solo strings that mourns the Germany he loved which was no more. Although this was only my second hearing of this Fantasia, I am convinced its mood is undoubtedly more elegiac than rhapsodic. The curtain rose to an audience applauding the orchestra who were seated in front of a plainly lit screen that for the Vaughan Williams was part blue and green perhaps hinting at something pastoral. For this first piece there were too many close-ups of Ticciati whose gestures are sometimes as flamboyant as his hair. It was noticeable how so few players actually ever looked up from their scores and – like Metamorphosen – I suspect it could be performed by such a small ensemble without a conductor. It was possible to indulge oneself in the slowly evolving, broad musical phrases and the solos from the featured string quartet (Pieter Schoeman, Tania Mazzetti [violins], Richard Waters [viola] and Pei-Jee Ng [cello]) were exceptional, though cellist Waters’s rich-tone and expressiveness stood out.

Ticciati said how ‘Mahler Four goes through an extraordinary journey. It goes from the peasants and the mud, almost Haydnesque in its quality, into the second movement where the devil is dancing on the back of the protagonist, then into a long, 20-minute slow movement, the climax of which is the appearance of the gates of heaven. Astonishing, wild, dangerous but full of hope. And then the last movement is a childlike view of what it is like to be in heaven. We go from the darkness into the light, into an ethereal place, full of magic and full of new music for Mahler after his Third Symphony.’

I didn’t do a headcount, but I think the size of the maskless LPO for Mahler’s Fourth Symphony was the bare minimum it needed. I was not in the auditorium, but I felt there was more light than darkness to be heard and the climaxes were underwhelming. To his credit Ticciati seemed to imbue every bar of the music with clarity and an almost celestial beauty: it is clear that his musicians were responsive to his vision if that is what it was. Mahler himself said how during its composition: ‘To my astonishment it became plain to me that I had entered a totally different realm, just as in a dream one imagines oneself wandering through the flower-scented garden of Elysium and it suddenly changes to a nightmare of finding oneself in a Hades full of terrors’. Well, for me, there were too few ‘terrors’ from Ticciati and his splendid orchestra.

Mahler’s mysteries and horrors were kept to the minimum in the first movement which was all rather jolly. Its orchestration is rather complex featuring as it does various percussion instruments including the wonderful opening sleighbells. There are a lot of parts for the wind instruments which were mightily impressive throughout, notably Benjamin Mellefont’s clarinet, Karen Jones’s flute and Jonathan Davies’s bassoon. That second movement is more tense though the horns introduce a short motif answered by the violins, which leads into a very lyrical passage. It can oddly sound like a slow movement (it is marked ‘At a leisurely pace’) but the sudden changes in tempo and dynamics, together with its abrupt ending, undoubtedly remind us that it is indeed the scherzo. Mahler’s annotation was ‘Totentanz Holbein: Der Tod führt uns’ (‘Holbein’s Dance of Death: Death leads us’) and here a skeleton’s beguiling Pied Piper-like fiddle playing leads the unwary to the land of ‘Beyond’. Death did seem to come behind a smiling face because Schoeman’s playing of his re-tuned violin never sounded devilish enough.

The third movement, which is the actual slow movement of the symphony (marked ‘Restful’) is beautiful and melancholic. The theme starts in the basses and then is gradually amplified by the whole orchestra, creating a wonderfully serene and magical atmosphere. (Mentioning ‘soundworlds’ one more time, as we heard Ticciati’s Mahler in this movement it was not that far removed from the earlier Vaughan Williams.) I would have preferred more tension from the contrasting middle section which disappears when the initial theme comes back. At the end of this movement there is a sudden outburst of E major (this movement is in G major), which anticipates the brilliance of how the Fourth Symphony ends.

The last movement features a soprano part, inspired by Mahler’s ongoing obsession with the Des Knaben Wunderhorn collection of poems, here he uses one he composed earlier, Das himmlische Leben, about the ‘joys’ of heaven which if we again look behind its mirror apparently includes much slaughter, as well as the attractive – to some – prospect of ‘eleven thousand virgins’. The music here is rather uncomplicated and follows closely the lyrics of the original tune and at the conclusion of this movement and the entire symphony there is ultimate joy but also a time for reflection and it seemed an eternity – well 45 seconds! – before Ticciati lowered his baton. The LPO had undoubtedly responded magnificently to all this heavenly rapture and produced wonderful – if slightly thinner than usual – string sounds that floated and shimmered gloriously.

I understand that the originally advertised soprano Elizabeth Watts was indisposed and so I cannot be too critical of her replacement Sally Matthews. I saw the wide-eyed innocence on her face of the child unmoved by the slaughter around her but did not hear anything childlike in her rather overly operatic voice.

Jim Pritchard

For more about Glyndebourne Festival 2021 click here.