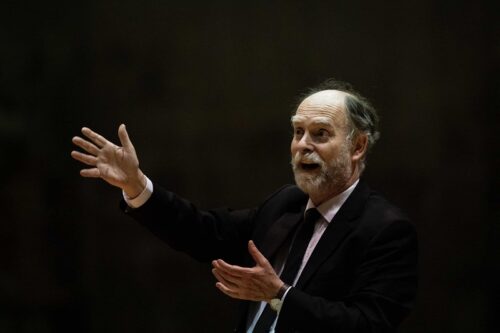

United Kingdom Vaughan Williams: Hannah Roper (violin), Jonathan Hope (organ), Catriona Holsgrove (soprano), Catherine Perfect (alto), Deryck Webb (tenor), James Geidt (baritone), Gloucester Choral Society / Adrian Partington (conductor). Gloucester Cathedral, 30.4.2022. (JQ)

United Kingdom Vaughan Williams: Hannah Roper (violin), Jonathan Hope (organ), Catriona Holsgrove (soprano), Catherine Perfect (alto), Deryck Webb (tenor), James Geidt (baritone), Gloucester Choral Society / Adrian Partington (conductor). Gloucester Cathedral, 30.4.2022. (JQ)

Vaughan Williams – Five Mystical Songs; Mass in G minor; Te Deum in G; The Lark Ascending; Serenade to Music; O, Clap your Hands

In this, the last concert of their 2021/22 season, Gloucester Choral Society (GCS) celebrated the 150th anniversary of the birth of Ralph Vaughan Williams. And what better place to celebrate this great English composer than in the very building where the ‘Tallis’ Fantasia was first unveiled to the world in 1910 and to which he was a regular visitor to conduct his works at the Three Choirs Festival. In fact, tonight there was a direct link with VW, the conductor. We were told, as part of the pre-concert announcements, that among the audience was Peter Hillier, a retired member of GCS, who had sung under VW’s baton at the 1953 Three Choirs Festival. I remember interviewing Peter for Seen and Heard (here) back in 2015, on the 300th anniversary of the Festival. Looking back at the interview after the concert, I found that the 1953 Festival was his first: he went on to sing in more than 50 consecutive Festivals.

The current generation of Gloucester singers offered a programme of quintessential VW pieces. They began with the Five Mystical Songs, for which they were joined by James Geidt. I liked much of what Geidt did. He sang with sensitivity and even though my seat was well back in the nave, I had no trouble making out the words. I noted however, some evidence of strain at the top of his voice, especially when singing loudly. Perhaps this happened because he was working hard to project down the long nave. The choral elements are limited in the first four songs but the choir’s contributions were consistently good, before they rounded off the set with a spirited rendition of ‘Antiphon’. I have sung in performances of these wonderful songs several times, so I am sufficiently familiar with the music to know that the singers observed VW’s dynamic markings scrupulously throughout.

The Mass in G minor (1921) is a remarkable work in which VW reaches back across the centuries and pays homage to the Tudor masters, just as he had done in the ‘Tallis’ Fantasia. It is a long time since I heard the work performed by a large choir; most of the performances I have encountered, whether live or on disc, have been given by chamber-sized ensembles. Any worries I might have had about whether a large choir would be insufficiently flexible in this music – and in this acoustic – were immediately dispelled. The writing in the Mass is challenging. Not only is the music itself technically demanding but VW adds to the complexity through his scoring: the layout is for double choir with solos and semi-choruses from within the ensemble. Adrian Partington had clearly prepared the singers very carefully and full justice was done to VWs rich textures. Whether in the quiet, contemplative music or in the more exuberant sections, I enjoyed and admired this performance of VW’s a cappella masterpiece very much.

The second half got under way with a performance of the double-choir Te Deum which VW composed in 1928 for the enthronement of the Archbishop of Canterbury. This is an excellent piece but it’s not heard as often as it deserves to be, indeed, I don’t think I have experienced it live in more than fifty years of concert-going. A committed performance made a very good case for the piece.

There followed something of a rarity: The Lark Ascending. No, I haven’t taken leave of my senses. The Lark is firmly established as probably the public’s favourite piece by Vaughan Williams. However, it is usually heard in its orchestral guise; it is rarer to hear it with organ accompaniment. As the very good programme notes pointed out, VW originally conceived the work in 1914, and it was first performed in a version for violin and piano in 1920: it was not until 1921 that he orchestrated it to such excellent effect. What the programme didn’t mention was that during the inter-war years several leading violinists performed the work with organ accompaniment, presumably with at least the tacit approval of the composer. Indeed, both Albert Sammons and Jelly d’Arányi are known to have performed it in Gloucester Cathedral: I believe that on both occasions Herbert Sumsion was the organist. By coincidence, what I think is the premiere recording of an organ version has recently been released (review). I have not yet heard that recording so I was keen to hear the piece performed live.

Violinist Hannah Roper achieved something of a coup by playing from a position on top of the organ screen, standing close to the organ console. Her playing projected beautifully down the cathedral nave and with the sound of the violin coming from on high the effect was highly atmospheric. She played the demanding solo part with poetry and virtuoso technique. I don’t know if Jonathan Hope was using the same organ transcription as the one heard on the aforementioned recording; probably not, but he made a beautifully calibrated and sensitive contribution to the performance. I have heard The Lark played with piano accompaniment, but on a first hearing it seems to me that the organ, with its sustaining capability, offers a much better alternative.

Serenade to Music is an incomparably magical composition. Originally composed for sixteen solo voices, it makes its full effect when heard in that version and with orchestral accompaniment. There are various other arrangements, however, and of these I think the only really satisfactory one is for a solo quartet and SATB chorus, which is what we heard. This was a satisfying performance in which the chorus sang the passages which VW had originally devised for the ensemble of sixteen soloists. The short individual solo passages can be easily allotted to a quartet; in this performance I thought the contributions of the two female soloists were the best. Partington imparted an ideal degree of flow to the music and Hope’s organ playing was full of finesse, though in such a version one loses the radiance of the solo violin line at the start and close of the piece.

The concert closed with a lively account of O, Clap your Hands, the short, extrovert setting of words from Psalm 47 which VW composed in 1919. The choir attacked this music with confidence and relish, making it an ideally joyful conclusion to this celebration of Vaughan Williams.

I enjoyed this concert very much indeed. The programme had been chosen discerningly to offer an excellent selection of Vaughan Williams’s music, including several ‘plums’. Such music is meat and drink to Adrian Partington, who had obviously prepared the choir with scrupulous attention to detail; he conducted all the choral pieces with evident understanding of and empathy for VW’s idiom. Following a recent catastrophic failure, the Gloucester Cathedral organ is out of commission; I understand it requires a comprehensive rebuild. The Cathedral had obtained on loan a substantial electronic instrument which was, I believe, previously owned by the late Carlo Curley. Its resources are not as great as one is accustomed to hearing from the Cathedral’s main organ but after only a few weeks to familiarise himself with this instrument Jonathan Hope clearly has its measure and his accompaniments were consistently excellent. So too was the singing of Gloucester Choral Society who I was hearing for the first time since Covid restrictions have been lifted. They were polished, committed and demonstrated fine attention to detail.

My one disappointment was the size of the audience. There were many empty seats, which was a surprise: in my experience GCS concerts attracted an audience which filled the cathedral nave in the pre-pandemic days. Probably there is still some residual Covid nervousness but I strongly suspect that many music lovers haven’t yet recovered the concert-going habit which was disturbed by the restrictions linked to the pandemic. If I am right, this is a serious threat to amateur music-making bodies; they need their audiences back, both for the stimulus of performing to crowds and also for the vital revenue they bring. Gloucester Choral Society – and I’m sure, many comparable organisations – have got their mojo back; we, the concert-going public need to get ours back as well.

However, it would be wrong not to end this review on a positive note. Those of us who gathered in Gloucester Cathedral on Saturday evening heard a fine celebration of one of England’s greatest composers.

John Quinn