United Kingdom Nureyev Legend and Legacy: Dancers, Royal Ballet Sinfonia / David Briskin (music director/conductor). Theatre Royal Drury Lane, London, 5.9.2022. (JPr)

United Kingdom Nureyev Legend and Legacy: Dancers, Royal Ballet Sinfonia / David Briskin (music director/conductor). Theatre Royal Drury Lane, London, 5.9.2022. (JPr)

2022 has no particular anniversary significance to Rudolf Nureyev but these five performances – and subsequent availability on Marquee TV (from 16 September) – will make balletomanes of the current generation more aware of how important Rudolf Nureyev was to many of us (now of a certain age) who actually saw him dance. It is 84 years since his birth and 29 years since his deeply sad, premature death. We will never see his like again, but he can never be forgotten because of his zealotry in always giving male dancers – himself first and foremost – as much to do as possible in any new version of the classics. He may not have always got the balance perfectly right; but what he did was often thought-provoking and spectacular, as witnessed by his stagings of Sleeping Beauty (1975) and Romeo and Juliet (1977) for London Festival Ballet (as English National Ballet was then) that I grew up going to see time and again. There were several evenings at Covent Garden too, and in the 1980s I saw him dance in his wonderful Vienna Swan Lake that he created in 1964. That remains in their repertory to this day (review click here), and it was one of my most memorable evenings ever at the ballet.

Ralph Fiennes and Dame Monica Mason were present at the start to introduce the event and after the interval there were some appreciations of Nureyev from a few of the dancers who were performing but were clearly much too young to have seen anything of him other than in archive footage. It is worth repeating here some words written by the legendary ballet critic, the late Clement Crisp, with which I wholeheartedly agree as he explained how Nureyev was a ‘stellar stage presence, and an insatiable, unassuageable performer. It seemed that no stage was too inconsiderable, no vast auditorium too large, to offer him the chance to perform, to display that seemingly irresistible presence. Month-long engagements – “Rudolf Nureyev will appear at every performance” boasted the publicity – testified to his drawing power, his dedication to dancing, his eclectic choices of repertory. He could, and did, galvanise ensembles as well as box offices and, most tellingly, audiences who might otherwise not have considered ballet as something worthy of their cash and their attentions. He served as example for a huge public of what dancing in the theatre could mean, and for the more critical eye, of what stellar presence could do to rehabilitate ballets, or to blend choreography to his own technical and idiosyncratic ends, or to cast some transforming spell over inept, fatuous creation.’

As Ralph Fiennes explained, ‘I think it is the spirit of drama which must link dancers and actors and it is the dramatic spirit of Nureyev which has inspired me … I attempted to make a film about Rudolf Nureyev, The White Crow, the young Rudolf Nureyev because his story moved me, not so much the dancing. I can admire the dancing … but his will moved me, his will to challenge himself to fully become himself as a dancer, as a human being, as a gay man. He inspired me chiefly because in a supreme moment of courage he made a choice … his defection in 1961 from the Soviet Union to the West. This was I believe a brave and spontaneous act of self-realisation rooted in a deep instinct to exist and dance in a world where expression in dance, expression as a performer – and by implication – the expression of his whole being, could be allowed to flourish without restraint.’ (His words in full should be available – along with those of Dame Monica Mason who suggested Nureyev wanted to ‘poison us all with his passion’ – in the recording on Marquee TV.) Significantly, Nureyev’s 1961 London debut was at a gala organised by Margot Fonteyn in this very same Theatre Royal Drury Lane.

But as regards any introduction that was it and sadly the rest of the evening had the same faults of most of these types of ballet galas. Unidentified dancers performing unannounced excerpts. I did read nearly every word of the programme but still could not remember everything and everyone we were watching, particularly when it was something I had not seen before and with dancers I did not recognise. This does not seem to matter to anyone as surely something would have been done about this by now.

Don’t get me wrong, there was so very much to enjoy, and memories rekindled in an eclectic programme of extracts from ballets all with some association with Nureyev, even if they weren’t always the first that came to mind when recalling his performances, no Swan Lake and no Romeo and Juliet for instance. Oddly, for me, at the end of the evening it was the female dancers who mostly outshone their male counterparts, and no problem in that, since as Nureyev’s frequent partner, the late Carla Fracci, once said: ‘He didn’t partner his ballerina, he danced with her.’

Artistic director Nehemiah Kish blended the more familiar The Sleeping Beauty, La Bayadère, Giselle and Le Corsaire with less well-known works, Gayane, The Flower Festival in Genzano, Laurencia and Don Juan. The presentation wasn’t ideal with the Royal Ballet Sinfonia to the rear of the stage and cutting down the – frequently inconsistently lit – performing space. Unfortunately, despite actually playing everything live under conductor David Briskin the sound was over-amplified and sounded pre-recorded.

The solo Nureyev created for the Act II The Sleeping Beauty entr’acte was a disappointing start and perhaps this was not entirely the fault of Guillaume Côté, who was supposed to be dancing in a later performance and may not have been fully prepared. He survived Nureyev’s typical tricksy steps but there was no characterisation when this – and his similar solo in Swan Lake – singles the prince out as someone more complex than we usually see.

Gayane is a typical piece of Soviet propaganda but introduced the only female choreographer in the programme, Nina Anisimova, and we saw her folk dance-inspired pas de deux from the charming Maia Makhateli and the amusingly posturing and preening Oleg Ivenko, Fiennes’s Nureyev in The White Crow. The pas de deux from La Bayadère was another disappointment given its significance to the Nureyev ‘legend’ with everything rather too tentative from Iana Salenko and Xander Parish.

Much, much, better was The Flower Festival in Genzano, with English National Ballet’s Francesco Gabriele Frola excelling in Bournonville’s signature speedy footwork and bouncy jumps partnering a pert – last-minute replacement – Ida Praetorius. Laurencia is another message-ridden Soviet ballet but had great significance to Nureyev’s early success and Natalia Osipova staged Vakhtang Chabukiani’s pas de six for herself and five dancers from The Royal Ballet. Great fun was had by all six, with Osipova’s extravagant jetés recalling some earlier performances I saw from her in Don Quixote. Cesar Corrales was stepping in (!) for a previously announced dancer and created the first – and eagerly-awaited – wow factor of the gala as he appeared to defy gravity and devour the stage as he leapt around.

Vadim Muntagirov is The Royal Ballet’s leading male dancer – and one of the world’s very best – and danced The Sleeping Beauty Grand pas de deux with English National Ballet’s Natascha Mair. She is someone who I have been waiting to see live ever since she came to my attention in a Vienna livestream of Nureyev’s The Nutcracker (review click here) and her glittering virtuosity impressed me again. Muntagirov was, as ever, the perfect partner and the epitome of regal presence, style, and razor-sharp technique. Shown in a pre-recorded video about Nureyev, Muntagirov seemed – like his dancing – so thoroughly nice with no ego whatsoever. He was a delight when discussing the demands of Nureyev’s roles and gave his heartfelt appreciation to The Rudolf Nureyev Foundation whose financial support had meant he could study at The Royal Ballet School.

The Act II pas de deux from Giselle featured perhaps the best performance I have seen from The Royal Ballet’s Francesca Hayward who was as ethereal as one could wish; though William Bracewell was rather underpowered and detached as her Albrecht. Something of an oddity next, a downbeat duet from John Neumeier’s Don Juan where Alexandr Trusch’s Don Juan stoically confronted Alina Cojocaru’s The Angel of Death. Any opportunity to see the remarkable Cojocaru dance is very welcome and I found it impossible to take my eyes off her.

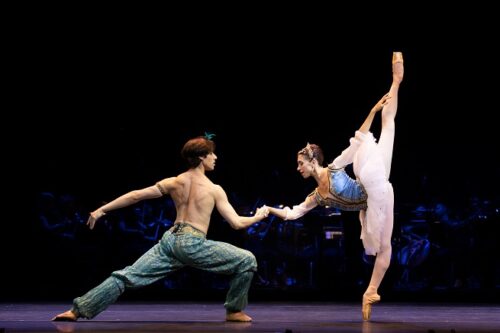

The best of all was left till last, the pas de deux from Le Corsaire which we know was so significant to Nureyev’s rise to prominence. The flamboyance and wild pantherine presence of Cesar Corrales finally challenged the memory of the unforgettable Russian dancer and all but over-shadowed – his colleague at The Royal Ballet – Yasmin Naghdi’s quicksilver elegance.

Jim Pritchard

Artistic Team:

Artistic director – Nehemiah Kish

Assistant Artistic director – Elena Glurjidze

Lighting designer – Simon Bennison

Costume designer – Natalia Stewart

Film director – Kim Brandstrup

The Sleeping Beauty, Act II Entr’acte solo

Choreography – Rudolf Nureyev

Dancer – Guillaume Côté

Gayane, pas de deux

Choreography – Rudolf Nureyev after Nina Anisimova

Dancers – Maia Makhateli and Oleg Ivenko

La Bayadère, Act II pas de deux

Choreography – Marius Petipa

Dancers – Iana Salenko and Xander Parish

The Flower Festival in Genzano, pas de deux

Choreography – August Bournonville

Dancers – Francesco Gabriele Frola and Ida Praetorius

Laurencia, pas de six

Choreography – Rudolf Nureyev after Vakhtang Chabukiani

Dancers – Natalia Osipova, Cesar Corrales,

Yuhui Choe, Marianna Tsembenhoi, Benjamin Ella, Daichi Ikarashi

The Sleeping Beauty, Act III Grand pas de deux

Choreography – Rudolf Nureyev after Marius Petipa

Dancers – Natascha Mair and Vadim Muntagirov

Giselle, Act II pas de deux

Choreography – Marius Petipa after Jean Coralli and Jules Perrot

Dancers – Francesca Hayward and William Bracewell

Don Juan, pas de deux

Choreography – John Neumeier

Dancers – Alina Cojocaru and Alexandr Trusch

Le Corsaire, pas de deux

Choreography – Marius Petipa

Dancers – Yasmine Naghdi and Cesar Corrales