Italy Kenneth MacMillan’s L’histoire de Manon: Dancers and Orchestra of La Scala Theatre Ballet / Paul Connelly (conductor). Broadcast live (directed by Stefania Grimaldi) from La Scala, Milan, 8.7.2024. (JPr)

Italy Kenneth MacMillan’s L’histoire de Manon: Dancers and Orchestra of La Scala Theatre Ballet / Paul Connelly (conductor). Broadcast live (directed by Stefania Grimaldi) from La Scala, Milan, 8.7.2024. (JPr)

Production:

Choreography – Kenneth Macmillan

Music – Jules Massenet

Arrangement and Orchestration – Martin Yates

Sets and Costumes – Nicholas Geōrgiadīs

Restaged by Julie Lincoln

Cast included:

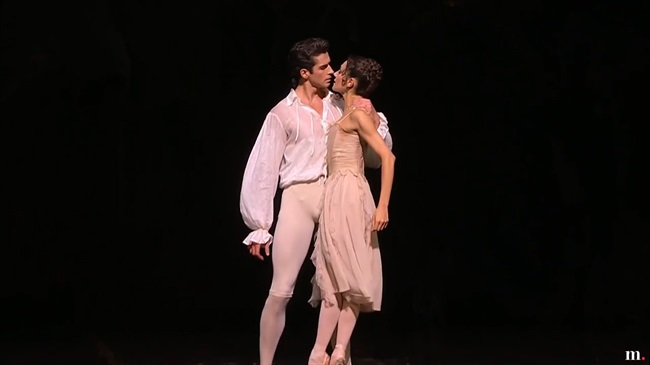

Manon – Nicoletta Manni

Des Grieux – Reece Clarke

Lescaut – Nicola Del Freo

Monsieur G.M. – Gabriele Corrado

Lescaut’s Mistress – Martina Arduino

Madame – Francesca Podini

The Gaoler – Gioacchino Starace

Beggar Chief – Domenico Di Cristo

Sometimes you don’t have to think too much about what you are seeing and just go along for the ride. We live in a world where there are trigger warnings about almost everything it seems. The latest in the UK is that the TV detective series Midsomer Murders (known in some countries as Barnaby) may contain murders! I have always left others to decide about famed choreographer Kenneth MacMillan’s Manon – first danced by The Royal Ballet in 1974 – which is very much of its time and a more innocent world.

The story originated in Abbé Prévost’s 1731 novel, and the setting is eighteenth-century Paris where it seems people were either rich and powerful, taking a particularly keen interest in the lives of the women on the fringes of respectable society, or poor and destitute with criminality or prostitution the only escape routes from their plight. What MacMillan has left us with is literally a riches-to-rags story because it is mirrored by the late Nicholas Georgiadis’s designs with the almost ever-present backdrop of rags to contextualise all the opulence and finery we will see before it, at least in the first two acts. It begins in the bustling courtyard of an inn near Paris where there are beggars scrounging money where they can and courtesans parade around and are available to the man with the most to offer. One of the wonderful things about this La Scala performance was watching, thanks to the camera close-ups, those on the fringes of the action always doing some ‘business’ and making what we saw even more interesting.

The first two overlong acts are populated with prancing ‘women of ill repute’ happy to offer sexual gratification to rich older men before their downfall is rushed through in the significantly shorter Act III. Manon Lescaut is a teenager who cannot decide between the genuine love of the penniless Des Grieux, or the loveless luxury offered by rich roués foisted on her by her feckless brother, Lescaut. Manon is seemingly content to be exploited and her character’s arc during the ballet is from the convent-bound ingénue to kept-woman of foot-fetishist Monsieur G.M. and someone who is in thrall to her ill-gotten gains. Manon eventually decides to flee Paris and after a series of unfortunate events – including helping Des Grieux cheat to win money playing cards and then witnessing the death of her pimping brother – it has fatal consequences. Manon ends up as a convict who suffers the degrading and demeaning sex acts of her gaoler before dying in the swamps of Louisiana still loved by Des Grieux who she had earlier treated so callously.

It was the sort of dark story which greatly appealed to MacMillan, having a far-from-happy ending compared to many popular fairy-tale ballets. The more times I watch his Manon, the more it is clear he is recycling elements seen before in his legendary 1965 Romeo and Juliet.

MacMillan had been advised to avoid the opera scores of Puccini’s Manon Lescaut and Massenet’s own Manon and chose some of the latter composer’s lesser-known music. Conductor, composer and former dancer, Leighton Lucas, was tasked with compiling and orchestrating a selection of Massenet’s music and was assisted by pianist Hilda Gaunt. It was subsequently reorchestrated in 2011 by Martin Yates and that is what was heard at this performance. It is often difficult to shut your eyes and imagine anything like you are seeing when you open them again and I have taken issue with this in the past. One of Massenet’s best-known tunes – the lovely and reflective Élégie – is incorporated into each of the three acts and in Act II there is too much Spanish and Arabian music and later in Act III, as the convicts apparently wilt in the New Orleans heat, the music reaches lush – and rather inappropriate – romantic heights. However, none of this seemed to matter as much now, perhaps this was due to excellence of the orchestra – as heard through loudspeakers – under the baton of Paul Connelly.

MacMillan’s Manon has solos, duets, trios, complicated lower body work, extravagant lifts, glides and slides, as well as much rolling, dropping to floor and leaping for the townspeople and beggars. It remains a richly textured ballet and Lady Deborah MacMillan once revealed how the choreography was inspired by her late husband’s obsession with ice skating. The destitution, depravity and desire are all just a little too sanitised for 2024 even though Georgiadis’s sets and some of his costumes were looking now rather appropriately dusty and shabby.

The La Scala Theatre Ballet company have strength in depth and there were some very fine performances. Nicola Del Freo was a dramatically-credible Lescaut, the handsome charmer who – without compunction – pimps and swindles his way through life. His Act II ‘drunken’ pas de deux with Martina Arduino was as good as I have seen it. I don’t think I have seen Manon danced and acted better in the many performance I have seen since first I saw MacMillan’s version in 1980. The superb Nicoletta Manni created a real person onstage: there was the coquettishness of someone naively willing to be sold by her brother to the highest bidder, then her youthful and all-consuming passion for Des Grieux, before the clothes and jewellery Monsieur G.M. offers turns her head. There was plenty of angst in Act III, though one of the ballet’s failings is that there seems little evident remorse or regret for her doomed hapless lover whom she has dragged into a murky world of brothels, gambling and brutality.

How wonderful it was to see current Royal Ballet principal – the tall and long-limbed – Reece Clarke guesting as Des Grieux. I am always surprised he is not a slightly better actor, though otherwise he didn’t disappoint. Clarke was suitably boyish, naïve and willing to be ensnared by Manon and then dragged down by her. Clarke got several yearning or anguished solos to display an impressive talent from the very first one which showed-off his ability to turn ever-so slowly, dance ‘off centre’ and mould the steps into one totally natural – and seamless – arc of movement. For once the famous Act I bedroom scene didn’t look like a brother and sister mucking around but two young lovers giving in to their urges. As expected from Clarke, recently Natalia Osipova’s regular partner, his partnering of Manni was excellent. Their final moments together in the Louisianan swamp was equally impressive in every way. Manon is clinging to life – her hallucinations conjure up nightmarish images of her past life – and he is just clinging to hope. Manon’s death appeared to release a torrent of emotion from Clarke which he had somehow repressed before.

There were several other solid performances: of note, were Domenico Di Cristo’s fleet-footed, Beggar Chief and Martina Arduino who made a considerable impression as Lescaut’s louche and long-suffering Mistress. The assembled courtesans and harlots – costumed in russet and particularly reminiscent of MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet – were suitably playful, competitive and sluttish, presided over by Francesca Podini’s unscrupulous Madame. Gabriele Corrado’s intimidating Monsieur G. M. had no redeeming features whatsoever and was a sexual deviant searching for any new pleasures his wealth could get for him. Finally, Gioacchino Starace was the bullying and sadistic penal colony Gaoler, a callous user and abuser of women, who forces himself on the exhausted Manon. In 2024 this certainly now seems MacMillan’s unnecessary – and gratuitously unpleasant – addition to the original Abbé Prévost story.

Jim Pritchard