France Wagner, Lohengrin: Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of Opéra national de Paris / Alexander Soddy (conductor). Broadcast live (directed by Myriam Hoyer) from the Opéra Bastille, Paris, 24.10.2023 and available on medici.tv from 1.11.2023. (JPr)

France Wagner, Lohengrin: Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of Opéra national de Paris / Alexander Soddy (conductor). Broadcast live (directed by Myriam Hoyer) from the Opéra Bastille, Paris, 24.10.2023 and available on medici.tv from 1.11.2023. (JPr)

Kirill Serebrennikov – under house arrest and banned from leaving Russia until 2023 and now resident, I understand, in Berlin – makes his debut at the Paris Opera with this Lohengrin (a review of his Vienna Parsifal is here). A militaristic setting is nothing new in Wagner productions, neither is finding it set in a medical institution, nor the use of filmed sequences and video on stage, and certainly, one of the character’s dreaming the whole thing up is ‘old hat’. Serebrennikov gives us all of these, but it was utterly compelling theatre, at least as viewed in this broadcast where we saw the intense action presented in close-up. With the unfolding conflict in Gaza and the ongoing war in Ukraine the constant images of war, the horrors of war and its traumatic effects, including madness, injury and death, made this Lohengrin heartachingly real and raw.

We are certainly far removed from Antwerp’s Brabantine court in the tenth century and in Act I it is as though we journey into Elsa’s psychotic mind. During the prelude we see black-and-white footage of her in happier times following her younger brother Gottfried through woods and to the lake where he takes a swim before going off to war. Is it his reported death that causes Elsa’s psychotic episode? We see images of her incarceration and during the opera she will often be confined to a hospital bed, having disturbed dreams, being forcibly restrained by nurses or being pumped full of drugs. Clearly the audience must banish any thoughts of Wagner’s Lohengrin and the tale of Elsa of Brabant being accused by Count Telramund of murdering Gottfried, heir to Brabant’s Christian dynasty, while in fact, the sorceress Ortrud, Telramund’s wife, has cast a spell on Gottfried.

In the first act Serebrennikov shows Elsa’s confinement in a grey cell within a hospital overseen by Telramund (though initially he is a military man) and Ortrud. It has an en suite (!) shower room and there is much scribbling on the walls and ‘playing’ with barbed wire and creating crowns for King Henry and Ortrud. After the recent naked aged Erda in Covent Garden’s new Das Rheingold (review here) I thought we were to have a naked Elsa, but she was just one of three incarnations, one singing and two gyrating, often simultaneously, throughout the first act and showing Elsa’s chaotic reminiscences. Many of King Henry’s forces wear balaclavas and some have black opaque Daft Punk helmets. There is a large neon LED circle for some reason and it is clear not everything will make sense. Elsa is clearly thinking back and mimes Lohengrin’s opening ‘Nun sei bedankt, mein lieber Schwan!’ while he is unseen. The ‘swan’ is represented by two bare-chested male dancers each with one large wing. Lohengrin is in army fatigues and has a backpack and Elsa sinks down in ecstasy on his arrival. Fighting to prove Elsa’s innocence Lohengrin’s fight with Telramund is rather botched and looks as if it involved some flickering, stunted lightsabres. Elsa embraces her champion Lohengrin before the act ends and the stage clears and Lohengrin just wanders to Elsa’s toilet.

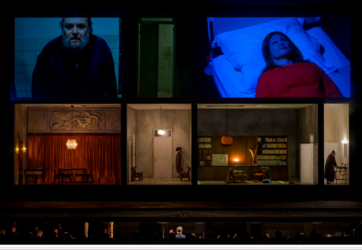

The Act II set is very reminiscent of the medical facility seen in Dmitri Tcherniakov’s recent Ring cycle in Berlin (review here). There are two levels with film and video shown above a communal room – with table, chairs, and a record player (!) – separated by a hallway from a library and that shower room where Telramund is at a sink threatening to shoot himself. Ortrud is seen to like a drink and Elsa in a red dress is wandering about and pursued by her nurses. Ortrud and Telramund put on white coats and go to her for a consultation. The décor does not look twenty-first century and is more like the 1980s and so is what we see the Soviet-Afghan war? The scene changes to the canteen, ward and morgue of the hospital with the soldiers happily gathering for a meal, recovering from their wounds or in body bags. King Henry appears and awards some campaign medals and Elsa appears to hand out some – not particularly fresh – flowers. It is all a bit overcrowded especially when the women appear, reuniting with their loved ones, consoling those who are injured, or mourning the dead. (To the consternation of the attendant, the naked bodies in their bags will come alive and walk out of the morgue!) Opposing each other across a bed at the front Ortrud will whip off Elsa’s wig and show her baldpate. Lohengrin will eventually calm her before the act finishes with Elsa having a fit on the bed and shown silently screaming above.

Act III begins with some projected German words ending (in translation) with ‘Hail to him, God sent! On! Don’t hesitate to argue, listen to the noble one’. To a degree Serebrennikov’s plot now loses the plot and we are on the frontline in a derelict warehouse with a long table on one side and a cameraman photographing the weddings of soldiers against a wall with a rug showing two swans. Elsa is in her own bridal gown with a bouquet of barbed wire and screwed up paper. At one point, Lohengrin looks as if he is ready to walk out on Elsa and to go off to fight again but they are reconciled and look as if they share a spliff. Soon however Elsa asks the forbidden questions of who her new husband actually is and where he has come from; once again, what happens to Telramund when he comes to wreak revenge on Lohengrin is not obvious at first viewing. Two alternate Elsas, Ortrud, four helmeted figures and some others enter: a prosthetic leg on the table seems significant and again there is no fight for Lohengrin and Telramund who just has a helmet put on his head before he withdraws. Lohengrin sets light to a paper rose as Elsa retreats to her bed.

The scene changes and King Henry makes his speech to his demoralised troops with several body bags at the front of the stage. The ‘hero of Brabant’ who is feted and given a medal is not Lohengrin: actually, when he eventually comes in he does not get the best of welcomes. Lohengrin will hold the false leg above his head before climbing on some fallen masonry to reveal everything about himself and pulling off his dog tag in the process. As Ortrud shows she is at the end of her tether, there is no horn or sword for Lohengrin to pass on, but he does have a ring as he unzips one of the body bags and Gottfried emerges riddled with bullet wounds. The opera ends with Elsa putting on a large barbed wire crown before slumping to the floor.

As heard through loudspeakers, musically, this Lohengrin was very good. If Piotr Beczała always seems to be Piotr Beczała in whatever role he sings that is not to suggest he does not delight the ear as Lohengrin with almost never an ugly sound heard. Beczała’s voice did seem a little darker than in previous years, yet every word is clear, sung lyrically with indefatigable stamina and ethereal refinement of tone where appropriate (how beautiful was his final act ‘Mein lieber Schwan!’ with his back to the audience). He has solid support from Johanni von Oostrum (a name new to me, I believe) as Elsa and Ekaterina Gubanova’s Ortrud. Von Oostrum perhaps is not the most radiant of Elsa’s but her commitment to Serebrennikov’s vision of her character was absolute. The latter can be said, too, of Gubanova and she was not the most demonic of Ortruds I have seen and heard when some like Petra Lang could pin you back in your seats with her Act II ‘Enweihte gotter!’ Wolfgang Koch was a grizzled, gruff, downtrodden, Alberich-like Telramund, whilst Kwangchul Youn repeated his familiar stoic and dignified King Henry and Shenyang was a firmly, authoritative Herald.

It was fascinating to have a (relatively) little-known British conductor Alexander Soddy conducting Paris Opera’s magnificent chorus and outstanding orchestra animatedly and with unflagging energy (from what we saw of him in the pit). Soddy – general music director at the Nationaltheater Mannheim – shaped and phrased the music imaginatively and with a clear understanding of the opera’s dramatic arc.

Jim Pritchard

Production:

Director, Set and Costume design – Kirill Serebrennikov

Set design – Olga Pavluk

Costume design – Tatiana Dolmatovskaya

Lighting design – Franck Evin

Video – Alan Mandelshtam

Choreography – Evgeny Kulagin

Dramaturgy – Daniil Orlov

Chorus master – Ching-Lien Wu

Cast:

Heinrich der Vogler – Kwangchul Youn

Lohengrin – Piotr Beczała

Elsa von Brabant – Johanni van Oostrum

Friedrich von Telramund – Wolfgang Koch

Ortrud – Ekaterina Gubanova

The King’s Herald – Shenyang

Four Brabantine Nobles – Bernard Arrieta, Chae Hoon Baek, Julien Joguet, John Bernard

Four Pages – Isabelle Escalier, Joumana El-Amiouni, Caroline Bibas, Yasuko Arita