United Kingdom Donizetti, L’elisir d’amore: (Laurent Pelly’s production revived by Daniel Dooner): Soloists, orchestra and chorus of The Royal Opera / Bruno Campanella (conductor). Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London 13.11.2012. (JPr)

United Kingdom Donizetti, L’elisir d’amore: (Laurent Pelly’s production revived by Daniel Dooner): Soloists, orchestra and chorus of The Royal Opera / Bruno Campanella (conductor). Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London 13.11.2012. (JPr)

In my review when this co-production with the Opéra National de Paris was first performed by the Royal Opera exactly five years ago I wrote ‘What L’elisir needs is laughter and tears otherwise what’s the point? I counted only four potentially big laughs when the audience chuckled together rather than individually’ … and one of these was when a fast-moving Jack Russell terrier ran across the stage and then later back! Since the original director, Laurent Pelly, must be working at Covent Garden on his new production of Robert le diable he may have countenanced the changes to his original staging that rarely now misses a trick to give the audience something to laugh at.

In 2007 I felt all concerned were perhaps taking Donizetti’s 1832 melodramma giocosa a little too seriously even though the description does suggest a story with some humour rather than a comic opera. The story’s laughs come from the social mores of a small Italian village where Spring has sprung and love is in the air. Adina owns the local farm, her friend Giannetta and a group of those working on the land are having a siesta. Nemorino, a young villager, sadly laments he has nothing to offer Adina but love. Adina is urged on to read the story of Tristan who won the heart of Queen Isolde by drinking a magic love potion and Nemorino decides this is what he needs. The quack, Doctor Dulcamara arrives and sells him his ‘cure-all’ elixir so that he can win Adina’s heart – but to spite him, Adina announces her immediate marriage to a swaggering army sergeant. This ‘elixir’ turns out to be nothing but cheap Bordeaux but as in most rom-coms, after all the trials, tribulations and misunderstandings true love wins out in the end. The story is timeless and Donizetti’s music is potentially full of charm.

Originally important to this staging was how women were depicted in Italian post-war cinema, though this seems to have been diluted somewhat now with the much broader comedy. However a certain French ‘take’ on Italian peasant life remains and when the braggart sergeant swaggers in with his ‘little and large’ soldier companions I thought it was ‘Allo ‘Allo!’s Captain Bertorelli I was watching rather than Belcore. A huge ziggurat of hay bales is intelligently used during the first scene and Chantal’s Thomas’s set designs are solidly three-dimensional throughout; there is a hay-baler, a tractor, a roadside trattoria, bicycles and scooters and a lorry-load of Dulcamara’s ‘snake oil’. The passing of time is realised mainly by Joël Adam’s lighting that progresses from sun-drenched morning to the starry sky of evening.

The big scene change in Act I is accompanied by a front cloth with adverts entertainingly explaining how Doctor Dulcamara’s potion is the answer for everything – and I mean everything! – accompanied by suitable pastoral sounds, including crickets. (Thankfully this was just a short pause because of the Royal Opera’s efficient stage personnel, had this been the Metropolitan Opera each hay bale would have needed one person to move it and the scene change would have dragged on and on – see recent L’elisir review .)

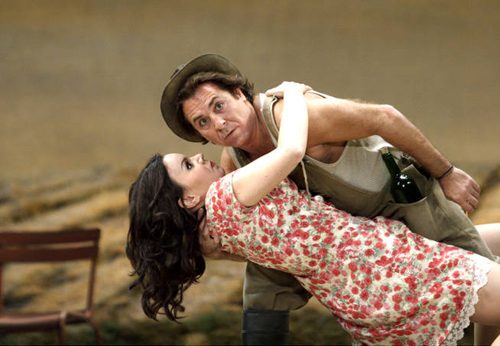

Starring in this revival is Roberto Alagna as Nemorino and it was a significant role for him early in his career but he has not sung it at Covent Garden until now. His commitment cannot be faulted and he climbs around haystacks, along the hay baler, up and down ladders enthusiastically. He does physical comedy very well; all the pratfalls, dancing and drunkenness was acted with a practiced ease that made him a very engaging Nemorino. It was a wonderfully endearing portrayal and with his felt hat he strongly reminded me of Chico, the dim-witted con artist member of the Marx Brothers. In recent years Alagna has been concentrating on heavier repertoire and seems only recently to have returned to this bel canto role – indeed he goes straight from this L’elisir to sing in Aida in New York. Initially his voice seemed in good shape and filled the theatre with a robust sound. It soon became obvious that any coloratura required the compliance of his conductor, Bruno Campanella, to slow things down for him to smooth out his legato and keep control of his voice. His top notes do not seem what they were and he covered the problem with one of them by throwing a hay bale over his shoulder at the exact moment! Unless my ears deceived me there was a blip soon after the start of his ‘Una furtiva lagrima’ from which he never really recovered. This really must be a show-stopper – I remember Nicolai Gedda reprising it at Covent Garden because of the storm of applause – here it was greeted politely but no one was likely to demand an encore this time.

To his credit he was a very willing part of a fine quartet of principal singers. Although Aleksandra Kurzak’s voice is heavier now than it once was she can still make coloratura effortless, singing with fluid ease; she was equally dramatically convincing as the flighty, manipulative and very sexy Adina who here is attracted to Nemorino from the outset, even if she perhaps doesn’t appreciate it. Nemorino gets a genuine rival in Fabio Capitanucci’s Belcore, well sung and swaggeringly confident of his own charisma. Man-mountain Ambrogio Maestri’s experienced Dulcamara effortlessly mixes comedy and sleaze. Even if his patter seems to be rushed at time during ‘Udite, o rustici’ he can be forgiven all for the amusing sibilant he employs during the Act II ‘Io son ricco, e tu sei bella’. Although there was an announcement made on her behalf, Jette Parker Young Artist, Susana Gaspar was a winsome Giannetta amongst a supporting cast that was just her and the Royal Opera’s always enthusiastic chorus, here representing a real farming community.

Bruno Campanella’s conducting brought us a L’elisir that was rather like a ballroom dance with its ‘quick-quick-slow’ moments, it will all surely settle down as the run continues. After a languid overture mostly it seemed a suitably lithe and well-paced interpretation even if there were some obvious coordination problems between stage and pit particular with the crowd scenes. Listen out for a familiar motif from Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde from Mark Packwood’s fortepiano continuo in Act II that was an inspired addition to Donizetti’s bucolic score.

Jim Pritchard