United States Mozart, The Magic Flute. LA Opera, James Conlon (conductor), Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, Los Angeles, 23.11.13-15.12.13 (JRo)

United States Mozart, The Magic Flute. LA Opera, James Conlon (conductor), Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, Los Angeles, 23.11.13-15.12.13 (JRo)

(©) Copyright 2013 Robert Millard www.MillardPhotos.com

There were unusual doings at the Los Angeles Opera last night. If your taste in opera is locked in the past, you should steer away from their new production of “The Magic Flute,” but if inventive, visually abundant, and clever re-imaginings of classic operas are your métier, then this is the production for you.

Originating at the Komische Oper Berlin and the brainchild of the director, Barrie Kosky and the English theater team of Suzanne Andrade and Paul Barritt, this is a “Flute” for wholly modern audiences who can process a visual field that was both over stimulating and incessantly entertaining. That the singers and orchestra were able to shine alongside this most dazzling and somewhat distracting production is a testimony to the beauty of Mozart’s opera, the quality of the first rate cast, and the perfection of the orchestra under James Conlon.

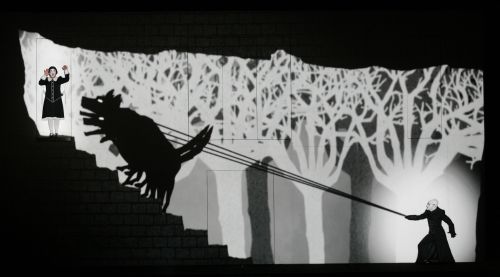

The eighteenth century setting was updated to the nineteen twenties and the result was delightful and insightful all at once. As I watched live singers interact with video projections reminiscent of German Expressionist cinema, American silent comedies, and early Disney animation sprinkled with Max Fleischer’s “Betty Boop,” I was struck by the feeling that I was experiencing “Flute” with the same wonder and enchantment encountered by the audiences of 1791 at Schikaneder’s Theater auf der Wieden on the outskirts of Vienna. Everything in the LA Opera’s “Flute” felt fresh and new, both modern and timeless all at once. There was an intimacy to the evening, perhaps better suited to a smaller venue than the Dorothy Chandler. Nevertheless, the audience felt embraced in the arms of this tender comedy, which brought the musical genre of German eighteenth century “singspiel” to life in the twenty-first century.

There were strengths and weaknesses to this remarkable assemblage of art and song. Here the silent film allusions worked to the benefit of composer Mozart and librettist Emanuel Schikaneder. Replacing the spoken lines (which brings the musical momentum to a dead halt) with written dialogue emblazoned over the characters heads was inspired. In these “silent” segments, the written lines were underscored with music from Mozart fantasias for piano, played on an eighteenth century fortepiano and seamlessly blended into the score. This tightened the action, moved the drama forward briskly, and eliminated the musical dead spots, which made for more engrossing entertainment. It did come at a price, however. Some narrative points were lost, like Papagena’s transformation from old hag to sexy youth, but it seemed worth the sacrifice if this production can draw and engage an audience beyond the opera crowd.

(©) Copyright 2013 Robert Millard www.MillardPhotos.com

But the most glaring mistake came in the rendering of the Queen of the Night. The ambiguity of the Queen’s morality, which is central to the plot (is she good or evil?), was done away with. In Act One, she is immediately revealed to be a rapacious spider woman, her gigantic, projected leg-claws chasing and entrapping Tamino, and her enlarged alien head (the masked head of singer Erika Miklósa) bobbing on a high pedestal above. Why would Tamino believe her when she tells him her daughter’s life must be saved from the evil clutches of Sarastro? It puts into question Tamino’s drive to rescue Pamina. Is he in love with her portrait, as written, or is he so terrified by the devouring spider-mother that he saves Pamina out of fear? Why not make her an exotic Weimar cabaret singer of dubious character or a decadent noblewoman to name a few possibilities. There is no nuance to her character, no movement from worried mother to frightening, narcissistic queen.

Elsewhere the visuals delight. Too numerous to explain at length, they cast a spell over the audience as the singers, with razor sharp timing, interact with the animation: from blowing animated smoke rings to jumping across rooftops. Tamino’s flute (oddly replaced with a naked Pamina fairy – don’t ask) tames a bevy of wild beasts who float in the night sky as constellations. Papageno, when offered wine by Sarastro’s priest, drinks a pink cocktail with an animated straw from a giant glass to hilarious effect. And in a wonderful touch, when the three ladies padlock his mouth, his lips dance in projection across the screen.

From the first majestic chords to the final notes of the score, the LA Opera orchestra, under Maestro Conlon, captured the vitality of this most ebullient of comic operas. There was a transparent delicacy to the music overlaid with a rich luster that conveyed every nuance of the music.

The role of Pamina, who not only survives her cunning mother and the lascivious Monostatos, but also the paternalistic clichés of the plot, was consummately sung by Janai Brugger. With a Louise Brooks wig, wearing white face, and dressed in schoolgirl black, she let loose a shimmering soprano. When she sings of her loss of love’s happiness in her Act Two aria, she caresses each line with tenderness, and the effect is exquisitely heartbreaking.

As her noble suitor, Tamino was sung by Lawrence Brownlee. His buttery tone and clarity of expression suited the role to a tee. Erika Miklósa, the Queen of the Night, is a seasoned player, having sung the role at least four hundred times. Glorious in Act One, delivering both nuance and power, she floundered in the opening of her famous second act aria and seemed a bit strident in her delivery. Monostatos, conceived as a Nosferatu creature, with a posse of enormous black, scruffy rats instead of slaves, was performed with lecherous relish by Rodell Rosel.

Sarastro, on the other hand, was underplayed by a dignified Evan Boyer. The production allowed him no latitude to interpret the role. He was glued to a perch high up on the projected screen and unfortunately outfitted in a stovepipe hat, white face, and long black beard. More Abe Lincoln than Guardian of the Sun, he was distanced from the audience by the architecture of the set, and his voice seemed constrained, particularly in the lower bass registers.

The Papageno of Rodion Pogossov was a wall-to-wall pleasure. With a silky, powerful baritone and comic presence that was able to outpunch even the most distracting animated effects, he embodied the bird-catcher as silent comedy hero and took us on a joy ride of an evening. Amanda Woodbury as his Papagena sung charmingly. In front of an adorable projection of a dollhouse, replete with dozens of children, the pair performed their closing duet to joyful effect.

The Three Ladies: Hae Ji Chang, Cassandra Zoe Velasco, and Peabody Southwell were a perfectly realized trio; and the chorus of the LA Opera under Grant Gershon sang with an emotional depth that touched the heart. One only wished that Sarastro’s priests looked less like tribal Abe Lincolns and more like the noble characters of the original conception.

With Pamina and Tamino’s trials conquered and the Queen of the Night defeated, we, along with the chorus, exulted in an evening well spent in the company of this very original production.

Jane Rosenberg