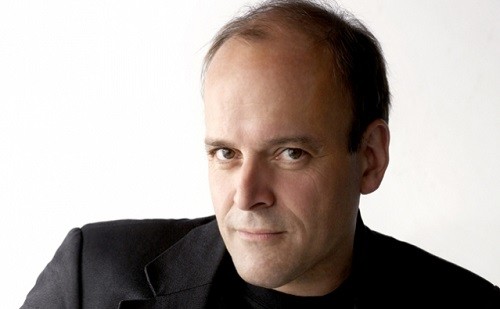

Canada Chopin: Louis Lortie (piano), Orpheum Theatre, Vancouver, 9.5.2017. (GN)

Canada Chopin: Louis Lortie (piano), Orpheum Theatre, Vancouver, 9.5.2017. (GN)

Chopin – Etudes, Op.10 and 25; 24 Preludes Op.28

Louis Lortie playing Chopin’s complete Etudes and Preludes at one sitting took me back in time to when listeners relished marathon events like hearing all 32 Beethoven Piano Sonatas performed consecutively. We have largely moved away from these exhausting adventures, but I looked forward to the prospect of this recital. This revered Canadian pianist has been a celebrated Chopin exponent ever since his early Chandos recordings of the 1980s, and the pristine clarity and elegance of his Etudes in particular have been long cited as a reference. One has noticed a greater imperiousness and bravura in the pianist’s performances of recent years, and both urgency and technical flourish were dominant features of this recital as well. This was perhaps no longer a young artist in love with Chopin, but a pianist who has mastered Chopin at the highest level of execution, and relished performing each of the 48 pieces in the most astute and demonstrative way. Accordingly, there was less focus on the cumulative line and balance within each group of pieces: each composition seemed to be a virtuoso ‘study’ which captured a given technical and emotional extreme. But there was plenty of cultivated wisdom to cherish, and the energy and attack exhibited was assuredly still that of a ‘young’ man.

It has been a long time since I heard Lortie play the Etudes in concert. I recall a very fine Queen Elizabeth Hall, London performance in the mid-90s distinguished by a wonderfully clean elegance and sparkle, but what was on offer here was much more purposive and less forgiving. I enjoyed the sense of tonal integration and sinew in the playing, particularly the emphasis on the left hand lines that often cut across the melody. Perhaps this is one advantage of playing a Fazioli, as was an often disarming degree of transparency. For all one might discount the titles for each of the Etudes, I also thought there was a genuine attempt to graphically portray these descriptions. Even the opening Etude of the Op.10 set, ‘Waterfall’, immediately dove into the irregularity and complexity of the implied motion, while #4 (‘Torrent’) had almost maniacal drive. On the other hand, there was seldom a feeling of space or contemplation or, for that matter, a coaxing suspension of the melodic line. #6 (‘Lament’) might have been the exception and was admirably searching but even it moved strongly into Lisztian breadth and involvement rather than intimate feeling. The echo effects in #9 were beautifully executed, and the boundless stream of notes fashioned in #10 was breathtaking, while the famous #12 (“Revolutionary’) had striking command and a true sense of the grand manner.

The Op. 25 set started from a gentler posture in #1 and, while the Etudes immediately following might seem to call out for moments of joy and charm, Lortie’s approach again kept them very much as tightly-knit studies. #7 was impressive in its gentle yearning, but the remaining pieces highlighted the volcanic fury in the composer, the last two in particular having an almost epic-dramatic quality. In many ways, this was supreme pianism, but I admit that I did not get the feeling of ‘glow’ at the end that I did two decades ago. There was a boldness and drama in this playing, and sometimes almost a demonic, frenzied Lisztian undercurrent to it all. Yet intellectual and technical rigour seemed to dominate – almost to the exclusion of easeful caprice.

There are few pieces in the composer’s oeuvre that draw one in more than the 24 Preludes, which combine physicality and wonder with the most touching nobility and melancholy. Lortie’s treatment did not aim at cohesive line as such, but certainly touched extremes. Again, the ‘study’ quality of the pieces stood out. That said, at the tempos chosen a lot of the pieces just flew, with strong accents, emphasis and almost unrivalled agility. The famous melancholic reveries (#6 and #15) were nicely textured but this was a rich, upholstered melancholy rather than a particularly personal one. I felt that the work was a catalogue of extreme responses, sometimes brought out in a larger-than-life way.

One can learn a lot from a didactic traversal of these two supreme works, but Lortie’s rarely moved in the direction of the beguiling or the comfortable; perhaps that was his point! His analytical rigour and transparency were admirable and his sheer pianism often eye-opening, but I still think the consistent gusto and drama on display portrayed the composer’s emotional volatility with less variety than there might be, and not much of a human face. Ultimately, I would prefer a less demonstrative profile, with a greater balance of charm, fantasy and intimate expression.

Rumour has it that this concert is the pianist’s ‘Farewell to Chopin’. If so, his desire to present a definitive statement is completely understandable. Lortie’s insights into this composer over a full three decades are to be cherished, and will be sorely missed on the concert stage.

Geoffrey Newman

Previously published in a slightly different form on http://www.vanclassicalmusic.com.