Switzerland Schreker, Die Gezeichneten: Soloists and Chorus of the Oper Zürich, Philharmonia Zürich / Vladimir Jurowski (conductor), Opernhaus Zürich, Zurich, 23.9.2018. (CCr)

Switzerland Schreker, Die Gezeichneten: Soloists and Chorus of the Oper Zürich, Philharmonia Zürich / Vladimir Jurowski (conductor), Opernhaus Zürich, Zurich, 23.9.2018. (CCr)

Cast:

Alviano Salvago – John Daszak

Duke Adorno – Christopher Purves

Count Tamare – Thomas Johannes Mayer

Nardi – Albert Pesendorfer

Carlotta – Catherine Naglestad

Guidobald Usodimare – Paul Curievici

Menaldo Negroni – Iain Milne

Michelotto Cibo – Oliver Widmer

Gonsalvo Fieschi – Cheyne Davidson

Julian Pinelli – Ildo Song

Paolo Calvi – Ruben Drole

First Senator – Nathan Haller

Second Senator – Dean Murphy

Third Senator – Alexander Kiechle

Production:

Director – Barrie Kosky

Set designer – Rufus Didwiszus

Costume designer – Klaus Bruns

Lighting – Franck Evin

Choir director – Janko Kastelic

Dramaturg – Kathrin Brunner

The story of Die Gezeichneten sounds a lot more unwieldly when it is summarised than when we hear it musically. A wealthy patron in the Renaissance city of Genoa (Alviano), disfigured and alone, has erected on a nearby island a sort of paradise that concentrates every imaginable artistic splendour. The implication is that hideous people need beautiful ones to sustain themselves. But Alviano never actually goes there; he doesn’t have the will. The problem is that so many other aristocrats do visit said island, and use it as a sort of 4-star harem. In other words, they kidnap women, enslave them, and rape them. Then they praise their good taste.

Alviano despairs and intends to dissolve his project by gifting the island to the people of Genoa; when negotiations begin for its transfer, nefarious schemes emerge amongst those who want to keep their orgies going. But Tamare, who should be leading the revolt, instead has his eye on a new girl, the artist Carlotta; she in turn rejects Tamare right as she realises she prefers the hideous figure of – you guessed it – Alviano. Tamare decides to ruin Carlotta, Carlotta decides to win Alviano’s trust, and Alviano decides to let himself be loved, overcoming his deep self-hatred, his revulsion at his ugliness.

In the end, it is Alviano left holding the bill for his island as the people revolt against the disappearing of their women, and to add insult to his injury, Carlotta’s fixation on him was aesthetic, not romantic. It turns out she does have time for Tamare after all. The third and final act is devoted to Alviano’s fighting and then accepting his demise.

Tenor John Daszak was given the role of a lifetime in this steely new production. Vocally, he achieved what few humans can do: open a German opera with a full voice and end it with an even fuller one. His diction sounded mother-tongue, used to entfremdend effect. His voice in the first act was piercingly clear, capable of legato shouting. Thirty minutes in, his forte top sounded strained, and I wondered where the night was headed. But as the orchestra tamed, something took hold in his singing, and there he was, summoning an elusive lyricism even amidst the cutting sound of his own notes and the score’s. By the third act, our hearts battered about at the sufferings of his desperate character, every sinew of the music and story drew towards Daszak’s centre, as he performed with extraordinary fervour and pain.

I say ‘steely’ because director Barrie Kosky did what he often does for his opera productions: stripped down the palate to its psychological essence, and added the crucial details from there. I imagine it must work something like this: he started by ‘visualising’ the tonal character of the work, which here is some sort of lush orchestral paradise for a violent and aestheticized society of lonely, selfish people; he used that psychological image as his framework; he then trimmed that image of every ounce of its fat, in order to give us a stage that doesn’t compete with the music but concentrates it. What worked so stupendously well for his Macbeth and Eugene Onegin works for the most part here too.

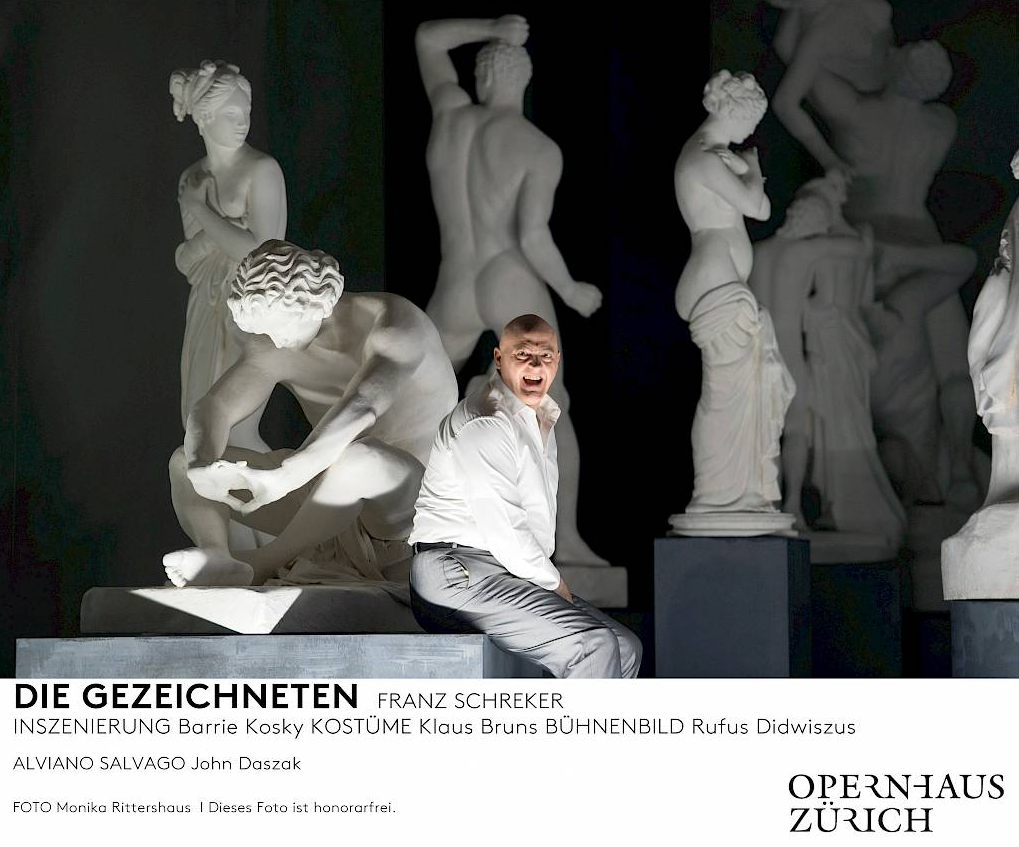

What does this approach mean for Die Gezeichneten? (The ambiguous title means ‘the stigmatised ones’, ‘the branded ones’, but also ‘the ones who are drawn’.) If Kosky can’t show us a literal version of the story’s distorted paradise – one that would require palm trees and exotic birds and all sorts of X-rated obscenities – he gives us an anti-paradise instead, all clean lines and blindingly white, suitable for Ikea absolutists. (Gaudy neo-Classicism also says hello.) The first act shows a museum-style private collection of classical statues, crammed into a room á la Citizen Kane, cast in cheap plaster and twisting the eternal grace of torsos into something much more libidinous. The second act misses a chance to build on this or switch it out; the only interesting changes are in the lighting, with Franck Evin giving us some creamy tones and some stark shadows. The third act, dark and far more abstracted, is one imaginative wallop after another, leaving us with Daszak’s extraordinary final pose.

Not every character’s staging is so affecting; Catherine Naglestad proffers her excellent Act II singing from the position of Carlotta’s potter’s wheel, at which she at first can only seem to produce a macabre blob of brown, wet clay. Alas, both the soprano and the production itself held back on the many possibilities to make her character seem more sinister, when she could be a sort of Dr. Caligari-cum-Jane rolled into one. She is obsessed with the art of the human hand, after all, and in this production, Alviano doesn’t have them. Very inconvenient, not having hands is. In Act II at least, Kosky could have used a little less Big Heat-era Fritz Lang and a little more Metropolis for depicting what’s so grotesque in this story. (Act III was extraordinary at this, a masterpiece of coherent restraint.)

Naglestad, like Daszak reviving her role from the recent Munich production of this opera, has a top that can cut through any orchestra, though I wished for more body in her bigger, first-act moments. The intimacy of the second act, however, afforded her the perfect setting to bring marvellous nuance and colour to her sound, both with and without big dynamics.

Several of her all-male peers stood out vocally as well; the production is extremely well cast. Baritone Christopher Purves is a terrific Duke Adorno, his dark vocal heft still allowing for the cynical smarminess his character needs towards the end of the story. Fellow baritone Thomas Johannes Mayer (Tamare, Carlotta’s tormentor-turned-lover) brought a satisfyingly boxy sound to his role, trading long-distance vibrato for a sort of angry squillo. Albert Pesendorfer (Carlotta’s father, the Podestà) started Act I a little wobbly on pitch but was a bold and lustrous presence by the night’s end. A tautly sung sextet of horny, hateful aristocratic men began the show – most of these singers are alumni of the house’s International Opera Studio, a guarantor of singing of this calibre. The chorus’s brief appearance towards the end of the opera was the best I’ve ever heard them. Both vocally and dramatically, they were harsh and vivid in ways that served the story.

Much of the applause not reserved for Daszak was poured forth onto conductor Vladimir Jurowski when he took the stage at the end. Jurowski coaxed from this orchestra the most intimate, phrenic, angular sounds conceivable. He and Kosky agreed to cut several later scenes, with a few arguments for doing so given in the programme. A) that Schreker’s music isn’t sacred, i.e. excellent, enough to leave exactly as written. B) that it would endure for nigh on three hours otherwise. And C) that cutting it heightens the harmonic intensity of the piece, which I can only agree with. A late post-Wagnerian romantic who saw the writing on the wall, Schreker’s piece is acclaimed for its ‘psychology’. Though he didn’t give each and every character and idea a leitmotif, he made up for it in lush and gnarly music that ceaselessly gives the tone of this very dark story. Jurowski’s delivery was masterful.

Why this opera for opening night of Zurich’s 2018-19 season? Perhaps because putting it on lured Kosky to the house for another remarkable new production; Zurich is lucky to have collaborators as imaginative and skilful as he (though don’t ask me why Kosky wore a t-shirt with an image of a young Joseph Stalin as he took his bows). Perhaps the reasons were actually socio-critical, as one would like to believe. I’m tempted to note that prostitution is legal in Switzerland, and that a new sex club with an 8-digit construction budget just opened in Zurich, a stone’s throw from the opera house. Are we the hideous ones consuming our way through what’s beautiful? If Kosky doesn’t show the story’s paradise of human crimes, it is because he doesn’t need to. The plaster of our urbane idols is enough, and it is cracking.

Casey Creel