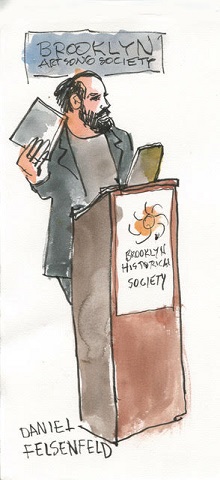

United States Brooklyn Art Song Society – Daniel Felsenfeld, In Context: Marie Marquis (soprano), Laura Strickling (soprano); Kate Maroney (mezzo-soprano), Chris Gross (cello), Michael Brofman (piano), Erika Switzer (piano), Chris Gross (cello), Brooklyn Historical Society, Brooklyn, 5.4.2019. (RP)

United States Brooklyn Art Song Society – Daniel Felsenfeld, In Context: Marie Marquis (soprano), Laura Strickling (soprano); Kate Maroney (mezzo-soprano), Chris Gross (cello), Michael Brofman (piano), Erika Switzer (piano), Chris Gross (cello), Brooklyn Historical Society, Brooklyn, 5.4.2019. (RP)

Daniel Felsenfeld – ‘The Law Falls Silent’, ‘To Clara’ (World Premiere, BASS Commission), ‘Writing’ (A Genuine Willingness to Help), ’A Most Beautiful Death’, ‘My Little Wicked Ways’

Clara Schumann – ‘Ich stand in dunklen Träumen’ Op.13 No.1, ‘Liebst du um Schönheit’ Op.12 No.4, ‘An einem lichten Morgen’ Op.23 No.2

Germaine Tailleferre – Six chansons françaises

Eve Beglarian – ‘All ways’, ‘Farther from the Heart’ (A Book of Days)

Whitney George – ‘A Night in Brooklyn’

Ruth Crawford Seeger – Two Ricercari

For the Brooklyn Art Song Society, ‘In Context’ equates to focusing on the works of a single composer and the music that has and continues to influence their work. Daniel Felsenfeld chose five women composers – Clara Schumann, Germaine Tailleferre, Ruth Crawford Seeger, Eve Beglarian and Whitney George – to be performed alongside five of his works for solo voice. The earlier composers, Schumann, Tailleferre and Seeger, were all phenomenal talents whose aspirations, to varying degrees, were shackled by the social norms of the time though they still managed to make a lasting impact, while Belgarian and George are active today.

Three songs of Clara Schumann, performed by soprano Marie Marquis and pianist Michael Brofman, opened the program. Schumann was one of the great pianists of her era, but composing took a back seat to her duties as wife and mother. Nowadays, however, her songs are regularly encountered on recital programs. Marquis’ bright soprano was ideal for three of Schumann’s best-known songs. Of particular interest was the accompaniment of ’An einem lichten Morgen’, which was splendidly played by Michael Brofman, the driving force behind BASS.

Germaine Tailleferre was a member of the group of twentieth-century French composers known as ‘Les Six’. In Six chansons françaises (1929), she channeled her experiences with men into love songs that are alternately tender, bawdy and irreverent. (Born Marcelle Taillefesse, she changed her name to spite her father who objected to her musical ambitions; her first husband threatened to shoot her in the stomach when he learned that she was pregnant.) Soprano Laura Strickling imbued them with a wry sensuality and ripeness, but airiness and sparkle were absent and missed by me.

One of the American ultramodernist school of composers, Ruth Crawford Seeger was told by an influential publisher of contemporary music that as a woman there was little chance that she would get her music published. Her output was sparse and sporadic, and the songs of Two Ricercari, ‘Sacco, Vanzetti’ and ‘Chinaman, Laundryman’ (1932), display an uncompromising style that coupled dissonance and serial techniques. The poems were by H. T. Tsiang, who immigrated to the US as a child and lived first in New York and then in Los Angeles.

Progressive in her politics, she set texts redolent of the era. The first deals with the 1921 trial and subsequent execution of anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti, whose convictions were driven by anti-left bias and prejudice against Italian immigrants. In the second, Tsiang addressed the discrimination and exploitation that Chinese immigrants encountered in America. It is intense music: the vocal lines are a mix of singing and Sprechstimme, and the counterpoint (as the title suggests) is at times dense and challenging. Mezzo-soprano Kate Maroney’s ease and naturalness as a performer, however, sold these songs, abetted by Brofman’s equally committed piano accompaniment.

Whitney George is a composer with an affinity for the macabre, the fantastic and the bizarre, but ‘A Night in Brooklyn’, in which she set a poem by Brooklyn’s poet laureate D. Nurkse for voice, cello and piano, is a love song. Cellist Chris Gross not only had beautiful cello melodies to spin, but also engaged in a dialogue with Marquis in which surveying the map of Brooklyn was a metaphor for exploring the contours of the body of a lover. In my program next to the poem, I wrote just one word: wonderful.

Eve Beglarian is a composer who really gets song. In ‘All ways’, she set just one line by Stephen King, ‘You don’t know don’t always’. It started as a low growl and escalated to a piercing wail, underpinned by jazzy, syncopated ostinatos. In ‘Farther from the Heart’, Beglarian set a bittersweet poem by Jane Bowles telling of the fear and isolation that can come with age. Her husband Paul Bowles’s version is a favorite of mine, and Beglarian’s setting, so different in every way except for an equally beautiful melody and the pangs of emotion that it evoked, was lovely, as was Maroney’s singing.

The focus, however, was on Felsenfeld, and this sampling of his over 200 songs displayed not only his ingenuity and craft in setting words to music, but also his refined and eclectic taste in texts. Raised in the suburbs of Los Angeles and now living in Brooklyn, Felsenfeld’s musical instincts are finely honed, with words and notes combining to create vivid musical landscapes. His music is sophisticated yet accessible. If Ruth Crawford Seeger was a role model, it was for her integrity and communicative powers, not her intense, take-no-hostages style.

‘To Clara’ was a BASS Commission and received its world premiere here by Strickland and pianist Erika Switzer. Felsenfeld depicts three points in his daughter Clara’s life: at the ages of eight (an excerpt from Emily Bronte’s Jane Eyre), 22 (a passage from Laura Mulvey’s Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema) and 45 (a lengthy extract from Brenda Shaughnessy’s So Much Synth), curated by his wife, Elizabeth Gold. I found the third song to be particularly evocative and moving.

Felsenfeld composed another three-song cycle, ‘The Law Falls Silent’, in response to the 2016 US presidential election and chose texts that are core to the American myth and the country’s aspirations: Emma Lazarus’s The New Colossus written in 1883 to raise money for the construction of a pedestal for the Statue of Liberty; Thomas Paine’s immortal words, ‘These are the times that try men’s souls’ from The American Crisis, published during the American Revolution; and Ralph Waldo Emerson’s ‘A Nation’s Strength’, which promotes following one’s own instincts rather than conforming to a societal dictates. The cycle was also a response to a challenge posed by soprano Lucy Shelton that he write something for unaccompanied soprano. Marquis rose to the challenge, delivering the message boldly with her impassioned singing.

Then there was a setting of ‘Writing’ from A Genuine Willingness to Help by Philip Littell (who wrote the libretto for Andre Previn’s opera, A Street Car Named Desire) that united all three singers, Goss on the cello and Switzer at the piano.

‘A Most Beautiful Death’ intertwines the spoken word and singing to create a provocative work of great emotional impact commemorating the assassination of John F. Kennedy. Eschewing the obvious, he set Arthur Kopek’s adaptation of a letter by Laura Huxley, the widow of English writer and philosopher Aldous Huxley, who also died on 22 November 1963, that details her husband’s death. A shot of LSD eased and perhaps hastened his final moments, which she administered as news of the shooting broke on the television. Maloney gave a remarkable, tour de force performance of the piece.

The final work on the program, ‘My Little Wicked Ways’, is Felsenfeld’s setting of three poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay. Each of the poems captures a memory of a love affair that was or might have been. Performed so beautifully by Maroney and Brofman, these, of all Felsenfeld’s songs, spoke to me the most.

Rick Perdian