United Kingdom Bach, Schumann, Beethoven: Piotr Anderszewski (Piano), Wigmore Hall, London, 3.5.2019. (CSa)

United Kingdom Bach, Schumann, Beethoven: Piotr Anderszewski (Piano), Wigmore Hall, London, 3.5.2019. (CSa)

JS Bach – Prelude and Fugue in E flat BWV876, Prelude and Fugue in A flat BWV886, Prelude and Fugue in G sharp minor BWV887

Schumann – Sieben Klavierstücke in Fughettenform Op.126

Beethoven – 33 Variations on a waltz by Diabelli Op.120

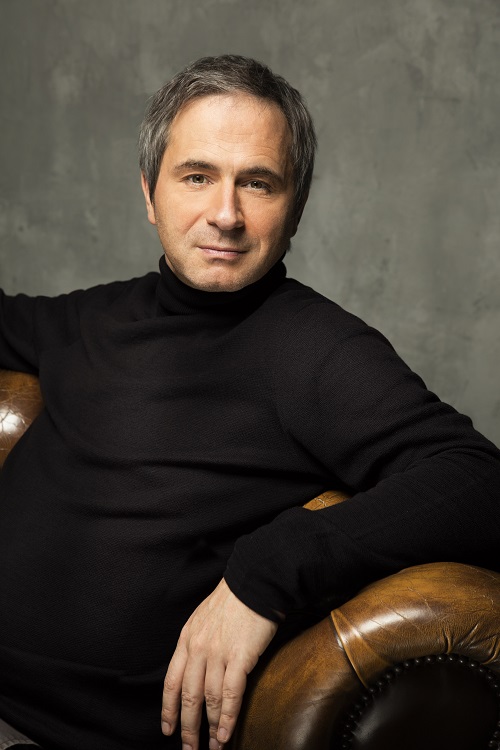

It was a seemingly unequal exchange of gifts. The great Polish pianist Piotr Anderszewski celebrated his 50th birthday at Wigmore Hall, and gave his audience a revelatory evening of Bach, Schumann and Beethoven before being presented by the management with a traditionally modest bottle of champagne.

Since his Leeds Piano Competition debut in 1990, the work for which Anderszewski is most closely identified occupied the second half of the recital, indeed, dominated the evening – Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations. Over the last 29 years, Anderszewski has become one its greatest exponents, performing it all over the world, recording it, and unfolding its myriad mysteries in a fascinating documentary by Swiss filmmaker Bruno Monsaingeon in 2000.

The provenance of these variations is well known. Anton Diabelli was a celebrated Viennese music publisher and amateur musician who had churned out a mundane waltz. As part of a publicity stunt, he approached some 50 composers, amongst whom were Schubert, Czerny, Hummel and Beethoven, with a request for a single variation. Initially dismissive, Beethoven declared the banal tune to be ‘a cobbler’s patch’ but went on to draft a set of 32 sublime variations ‘of every kind, character, and speed’ which start, to quote Anderszewski, ‘as a little single cell, but which eventually becomes a universe of human experience’.

Any performance of this piece places huge technical demands on the artist, of course, but this is not the only challenge. Also required are highly developed interpretative skills to contrast the work’s vast range of emotions, and an overarching vision to preserve its symmetry. In each respect Anderszewski’s performance was both masterful and mesmerising.

From the solemn introductory bars of Variation 1, where Beethoven parodies Diabelli’s original theme in the form of a stilted mock-heroic grand march, to the final Variation’s swelling Bach-like fugue and graceful minuet, Anderszewski, in a wonderfully shaded interpretation, contrasted passages of Beethovenian power with sections of great delicacy, and riffs of earthy humour with moments of poignant contemplation. The exuberant rhythmic climaxes in Variation 5: Allegro vivace, followed by the alternating trills and arpeggios in Variation 6, and dramatic sforzando octaves and whirling triplets in Variation 7 were note perfect and executed with dazzling edge-of-the seat virtuosity. This made the balmy account of Variation 8, a Brahms-like Poco vivace, all the sweeter. Similarly, the whirlwind Variation 10 Presto, judged by some to be the most brilliant of all, and played by Anderszewski at astonishing speed, served to emphasise the serenity of the quiet delicacy of the Allegretto in Variation 11.

It is perhaps invidious in such an integrated interpretation of these Variations to highlight favourite moments but, for me they come towards the end of the piece with Variations 26, 27, and 28 whose jagged rhythms and discordancy break through the barriers and conventions of nineteenth-century musical form. Here, Anderszewski brought to bear all his astonishing brilliance and imagination, while remaining loyal to the work’s creator.

In a last-minute change of programme in the concert’s first half, three Bach Preludes and Fugues from his Well-Tempered Clavier Book II, those in E flat, A flat, and G minor substituted Schumann’s Gesänge der Frühe Op.133. These were followed by Schuman’s Sieben Klavierstücke in Fughettenform Op.126. The Preludes and Fugues were finely articulated and played with great clarity, as was the Schumann. It is ultimately a matter of personal preference, but Anderszewski’s Bach sounded a little hard-edged and clinical when compared to gentler and more lyrical interpretations by pianists such as Andras Schiff or Murray Perahia.

The only disconcerting element in an otherwise illuminating evening was Anderszewski’s decision to play on a dimly lit platform. As a result, his face was visible, but his hands were all but obscured in the semi-darkness.

Chris Sallon