Italy Rossini, Matilde di Shabran. Orchestra and men’s voices of the Chorus of Teatro Comunale, Bologna. Adriatic Arena, Pesaro. 14.08.2012 (JB)

Italy Rossini, Matilde di Shabran. Orchestra and men’s voices of the Chorus of Teatro Comunale, Bologna. Adriatic Arena, Pesaro. 14.08.2012 (JB)

Cast:

Corradino, misogynist nobleman, known as Ironheart, Juan Diego Florez

Raimondo Lopez, a General at war with Ironheart, Marco Filippo Romano

Edoardo, his son, Anna Goryachova

Matilde di Shabran, hoping to claim Corradino in marriage, Olga Peretyatko

Contessa d’Arco, supposedly betrothed to Corradino, Chiara Chialli

Ginardo, gatekeeper at Corradino’s castle, Simon Orfila

Aliprando, Corradino’s doctor, Nicola Alaimo

Isidoro, a street entertainer aspiring to be a poet, Paolo Bordogna

Production:

Conductor, Michele Mariotti

Stage Director, Mario Martone (from his 2004 production in Pesaro)

Chorus master, Lorenzo Fratini

Costumes, Ursula Patzak

Sets, Sergio Tramonti

Lighting, Pasquale Mari

Photo Credits: Studio Amati Bacciardi

Technique is a composer’s craft; in exceptional cases, it is also his art. That is when style becomes content, when the technical proficiency is so seamless that the music sounds as though it composed itself. Bach and Mendelssohn are supreme examples of such fluency even as they are poles apart in styles. By the time Bach had written a prelude and fugue in every major and minor key (Book one of the 48) he was probably incapable of thinking of a musical subject that would not neatly work itself out as a fugue (Book two). How some of us struggled as composition students to think up a subject which would work as a fugue, only to have to abandon it when it didn’t !

Mendelssohn had technical fluency from an early age. Just think of the music for A Midsummer Night’s Dream or the E minor violin concerto (both teenage works). But he also dashed off works with the same fluency which sometimes sound like one of those damned machines of the sorcerer’s apprentice which will never stop, when you earnestly wish it would. Fluency but no art. Mozart is guilty of the same vice; while he is the author of some of the most sublime music, some of his scribblings are deadly dull. It’s simply not enough to set your fluency machinery running.

Rossini came out of a thirty-eight year retirement to write music which he called the sins of my old age. The dedication on the front page of his final piece, the Petite Mese Solonelle is in French and rather touching: Well, dear God, here it is, finished at last, my Little SolemnMass. Is it really sacred music or just more of the same damned stuff? I was born for comic opera as You know. No skill needed there, just a sense of style, that’s the long and short of it. So Glory to God, and please grant me Paradise. G. Rossini .Passy 1863.

You can see from the dedication that his irony had not abandoned him and should you be in any doubt, if you open the first page of the score, the first tempo indication says, Allegro Cristiano.

Rossini’s craft and also his art, relied on irony; in this art, in the world of music, he remains unsurpassed. And his self-deprecation as a master of opera buffa is certainly a pose and one he cannot possibly believe. For again, it is a field in which he reigns supreme. It is a truism that no one can parody you as well as yourself. Rossini exploited that truth. And he kept a straight face about it. Is there another composer who managed so artfully to do that?

Yet he almost never sat back and let his fluency machinery write the music. He often set himself an additional challenge which, in meeting it, brings out his best inventions. That was the case with Matilde di Shabran. He had been too busy supervising and conducting his own works and had handed over the opera to Pacini to finish writing the second act, which Pacini duly did for the Rome premiere in 1821. A little over a year later Rossini rewrote the opera, replacing Pacini’s contributions and with the added challenge of turning it into an opera semi-seria (surely the most difficult form for a master of comedy) , though the autograph score calls it a melodrama giocoso. (a double take there you will notice and one with scope for irony, his undeclared talent). It was in this form that it was first performed in Naples in November 1821. And this is the version which the Fondazione Rossini revived for its first Pesaro performance in 1996.

Mozart had given the world a drama giocoso in Prague in 1787, much aided by his librettist, Lorenzo da Ponte, whose very life, like that of the composer’s, could be aptly summed up as a drama giocoso. That undisputedly makes Don Giovanni the greatest work of its genre. Rossini was less lucky. Or more, depending on your point of view. Jacopo Ferretti, his librettist, was no match for da Ponte. But Rossini would show –and not for the first time- how he could take a cliché-ridden text and turn it into something vital.

Rossini made three other forays into the opera semi-seria, all of them well received: L’Inganno Felice (1813), Trovalo e Dorlinska (1815) and La Gazza Ladra (1817). Matilde di Shabran (1822) would be his last, unless you want to count the Petite Mese Solonelle (1863) –as above.

If you ask what is the other half of the opera semi-seria, Rossini seems to have rather a good answer: absurdity. As everyone knows, absurdity is a Rossini speciality. But taken seriously, of course. A rather good subtitle for Matilde might be Let’s all go bonkers together, but not forgetting our individuality.

Madscenes were standard fare in the early nineteenth century, usually reserved for the diva’s finale, but in Matilde’s Act one quintet (Questa è la dea?) and the Act two sextet (è palese il tradimento) all the characters go off their rockers while staying in character. That calls for contrapuntal writing that would have put even Bach to shame. Rossini’s technique of irony sparks his art of wit: never would he produce such accomplished pages. The Pesaro audience responded with a prolonged stampede of applause.

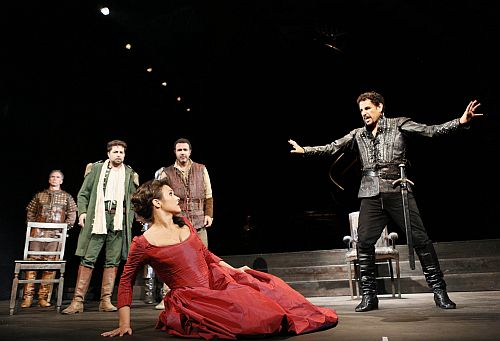

The ROF fist staged Matilde in 1996 at the Teatro Rossini (750 seats) then again in 2004. This is the same production transferred to the Adriatic Arena (1,200 seats) by the distinguished Neapolitan movie and theatre director, Mario Martone. Mr Martone is admired for his clean lines and no-fuss productions. These qualities were admirable here too with some excellent fizz added just at the moment when he music calls for it. Sergio Tramonti’s scene was basically sets of intertwining spiral staircases on revolving discs, wittily underscoring the sense of the nonsense.

Michele Mariotti paced the opera beautifully with pauses for breath in all the right places, even if for me, some of his phrases came out as a little prim. But I guess that I shouldn’t complain about that: primness is an aunt Sally which Rossini studiedly sets up for the sheer fun of knocking it down.

Ferretti (librettist) had originally wanted to call the opera Corradino Ironheart, but after Rossini persuaded him to change the heroine’s name from Isabella to Matilde, he also convinced him to change the opera’s title.

Corradino is all three ROF stagings was Juan Diego Florez. There is no other Rossini singer to stand alongside him. He is also an admirable member of an ensemble and no show-off, though goodness knows, he has lots of opportunities to do just that. But he is profoundly musical and flips through his virtuoso passages with the cheeky ease of buttercups sprouting through the earth of summer meadows.

Both leading ladies were impressive, in particular, Anna Goryachova in the role of Edoardo. She is slight of build, agile and balletic in movement and outstandingly dramatic in a vast range of vocal colours. A word of praise too for Stefano Pignatelli’s virtuoso horn playing in his duet with Edoardo –Sazia tu fossi alfine.

Olga Peretyatko was a beautiful Matilde, even if there were moments when Rossini’s outrageous fioratura demands caused her to sound like gargling. When the composer hands her the Rondo finale she sounded more relaxed and earned deserved thunderous applause.

The part of Isidoro –factotum, dog’s-body and prospective poet- has his part written in Neapolitan, so surtitles, which can often be a distraction, were essential here if you didn’t want to miss all the fun of the fair. Paolo Bordogna is Italy’s leading basso buffo and was physically and vocally perfect in the part. Nicolai Alaimo, Corradino’s hapless doctor, was another perfect bit of casting. The men of the chorus of Bologna’s Teatro Comunale sang and moved with precision and involvement.

Jack Buckley