United Kingdom Georg Friedrich Haas, Morgen und Abend (world première): Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal Opera House / Michael Boder (conductor). Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London 13.11.2015. (JPr)

United Kingdom Georg Friedrich Haas, Morgen und Abend (world première): Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal Opera House / Michael Boder (conductor). Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London 13.11.2015. (JPr)

Haas, Morgen und Abend

Cast:

Olai: Klaus Maria Brandauer

Johannes: Christoph Pohl

Signe/Midwife: Sarah Wegener

Peter: Will Hartmann

Erna: Helena Rasker

Production:

Libretto: Jon Fosse

Director: Graham Vick

Designer: Richard Hudson

Lighting designer: Giuseppe Di Iorio

Projections: 59 Productions

Sung in English and German

Translation: Hinrich Schmidt-Henkel (German) and Damion Searls (English)

I will come to Morgen und Abend (Morning and Evening) from another perspective, as I cannot spend time considering philosophy especially since as a scientist I am mainly concerned with how carbon-based lifeforms (we humans) are given birth to, live and then die … and our existence can be explained rationally not metaphysically. Never has the ‘Opera Essential’ precis – here included in the free cast sheet – been so essential! In the printed programme there was an essay (What Can It Mean?) so opaque that it made me doubt whether the reason I couldn’t understand what it was getting at was that I had learnt nothing worthwhile in my six decades. As I suspect that not to be the case, I will consider Morgen und Abend purely as an evening of new music rather than an existential treatise that I suspect it proposes to be.

The synopsis must be the shortest in opera history and says what we are watching ‘is the struggle of Johannes into and out of life’ … and that’s all apart from the fact it takes 90 minutes doing it. Some of it is hauntingly hypnotic and poignantly lyrical but it seemed like an over-inflated chamber opera and would have been better put on in the Linbury Studio Theatre if it were not for the huge orchestral forces it required. This was due mainly to two banks of percussion at either ends of the orchestra in what used to be the side seats of the Stalls Circle. It seems impossible to have a piece of contemporary music that does not utilise every possible percussion instrument there is, as well as, others they may invent.

It all begins with the banging of a big bass drum and some microtonality (aided by offstage choral effects) creates an ethereal soundworld redolent of the Norwegian homeland of novelist and playwright, Jon Fosse, whose libretto is an adaptation of his original novel. It is as if the world’s creation at the start of Wagner’s Das Rheingold has been put on replay loop. For at least 30 minutes it is deemed necessary to have a spoken monologue, a fisherman called Olai is anxiously awaiting the birth of his son Johannes. He goes on and on (probably ironically) about ‘Why is it so quiet?’ when it palpable isn’t and rails against his lot and reminded me of Tevye in Fiddler on the Roof. To some screaming the child is born offstage and for the remainder instead of this apparent Sprachtspiel we get some genuine opera – albeit rather drawn-out for such a simple premise. We now encounter Johannes as an old man and he is also a fisherman; in ‘reality’ he is bed-ridden and dying but we see him coming to the realisation that his death is imminent. Though both are dead, he meets again his wife, Erna, and his friend, Peter, whose hair he strangely has the urge to cut and whom he wants to take out fishing in his boat: there is a homoerotic subtext here and it appeared a homage to Peter Grimes. At the end Peter and Johannes debate what heaven might be like and conclude that ‘there is no You and Me’, ‘it is neither good nor not good’ and how everything Johannes loves is there and ‘everything you don’t love is not there.’

In this second half the vocal writing enhances the atmospherically eerie sounds – it can rarely be called music – we otherwise hear and is as if from another work. Nevertheless despite being sorely tested at times, everything is performed valiantly by five accomplished singers with standout performances from the trio of Christopher Poul as Johannes who is seeing dead people and breathing his last (but taking his time doing it); Will Hartmann as his dearest friend Peter, and Sarah Wegener as his caring daughter Signe. Under Michael Boder’s baton the orchestra plays effectively and committedly.

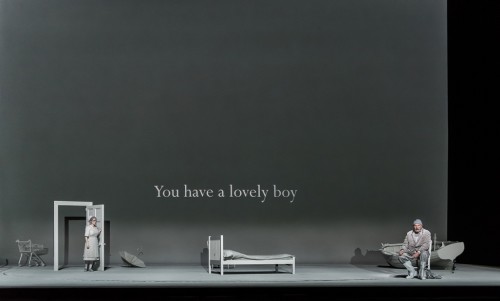

Graham Vick has little to direct here but does it efficiently in Richard Hudson’s spare grey box-like setting that literally shines the light onto the stage that is supposed to be at the end of the tunnel as death approaches. Little else is to be seen apart from three chairs, a door, an umbrella, a shopping trolley and a boat. The great Austrian actor, Klaus Maria Brandauer, intones the opening to Morgen und Abend in heavily-accented English, some of the dialogue is also in English but then reverts to German and I found this strange. Also it was deemed necessary to have the translation projected on the back of the stage and replicated as surtitles above it – and this gave me more to ponder on than the debate about Life and Death Georg Friedrich Haas and Jon Fosse were presenting on stage.

Morgen und Abend is a co-commission and co-production with Deutsche Oper Berlin who have more money to waste than The Royal Opera. After its performances in Berlin how soon will it be staged again … if ever? I was left with this reflection about ‘new music’ that so little is now written to last and how Mozart, Verdi, Wagner and Puccini will still be performed 50 years from now whilst Morgen und Abend will sadly just be a footnote in opera history.

Jim Pritchard

For further information about events at the Royal Opera House visit http://www.roh.org.uk/.